Bohra cuisine

Recipe by Fatema Kaka, a home-maker from Mumbai| The National

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Bohra cuisine and dining etiquette

The Bohras live by the saying, "Many hands are a blessing" and for dining this is an encouragement to eat in company. The traditional Bohra way of eating together is around a steel thaal the standard size of which is designed to accommodate a family or any group of 8 or 9 people during a communal dinner.

Bohra etiquette for meals requires that heads be covered and hands washed both before and after the meal. Thus, in a communal dinner or when guests are invited home, once everyone is seated, it is common for a serving member to go around with a chelamchi lota (basin and jug) and wash the guests' hands.

The thaal is elevated with a tarakti (stand) which is placed in the middle of a square piece of cloth called a safra, laid out on the floor. Out of respect for the bounty of food, a laden thaal should not be left unattended; it is not placed until at least one person is seated for the meal. During a community meal, the thaal is not placed until all eight diners are present, because the portions served are intended to suffice that number. Bohras have a no-wastage policy so not a single morsel should be left on the thaal when it is taken away.

Food is eaten using all five fingers, preferably of the right hand.

Each dish is placed in the centre of the thaal from where each member will take his or her share. The meal begins with a pinch of salt and after each diner has tasted it the first course is served.

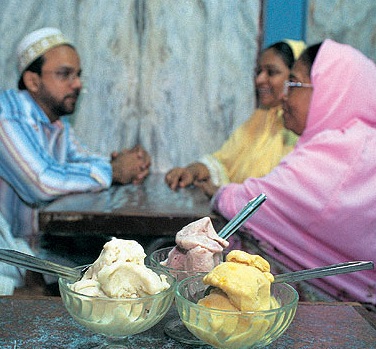

Interestingly, the first course is usually a dessert. In the Bohra dialect of Lisan-ul D`awat, desserts are called mithaas (sweets) and the savoury dishes kharaas. The first sweet dish can be either a traditional Indian sweetmeat or something modern like ice cream, unless it's a celebration, when the sodannu (a tiny serving of cooked rice with ghee and sugar) takes first place.

A savoury starter follows, accompanied by some form of bread before giving way to the main course. It used to be the case that at a Bohra feast, 2 or more courses of kharaas and mithaas were served alternately, but now - to promote healthy eating minimize waste - Bohras have been counselled to keep the number of sweet and savoury courses down and for public events there is to be no more than 1 each.

Taking a pinch of salt to start the meal

After the sweet and the savoury dish comes the main course; invariably a rice dish such as the signature Bohra meat biryani, kaari chaawal (meat broth with rice) or daal-chaawal or daal-chawaal palidu (lentil rice with soup with or without meat).

The Bohras have a wide variety of both vegetarian or non-vegetarian rice mixes for their main course.

Separate servings of soups and salads might well be served from the outset of the meal. When it's time for the jaman to end, it is also time to bring in the denouement of fruit or dry fruits.

Finally the family or dining members taste the salt again. The Prophet MohammedSA has said that this tasting of salt before and after meals prevents 72 major diseases.

At a festive communal meal the diners will likely finish with a mouth freshening paan (a betel leaf with various flavourings folded inside).

Bohra food at home, at feasts and in traditional inns

Shabnam Minwalla, The distinctive and delicious Bohra food, Outlook Traveller

Dig into the 'thaal' to know more about the Bohra Muslim community's traditions and food.

Bohra food suffers from the two unforgivable shortcomings of our times: poor PR and sloppy packaging. So, no matter that the cuisine is both distinctive and delicious, it performs lousily on the ethnic-chic scale. The very same foodies who are on coconut-and-cardamom terms with Konkani gassis and Chettinad curries have barely heard of masoor-daal gosh pulao and malai khaja. Indeed, the challenges thrown up by an image makeover are enough to daunt the cockiest PRO. For starters, Bohra cuisine is widely believed to comprise a single dish—and the minute a festival or birthday strolls within sight, various Tasneems and Tahirs are confronted with the inevitable, “Don’t forget to bring some biryani for me.” The few eateries that counter this perception are tucked away in Mumbai’s congested mohallas—and even determined seekers of that “tiny joint serving marvellous malpua malai” are discouraged by tales of parking troubles and filched hub-caps.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle in the path of gastronomic glory, however, is the ‘eeks’ factor. For the true Bohra feast—a fabulous procession of hand-churned icecreams, halwas, soups, tandoored chickens and pulaos—is consumed in a thaal. About eight peckish souls sit on the floor along the circumference of a large, flat metal dish that looks a bit like a flying saucer (and is just as alien to most non-Bohras). While they wait expectantly, the first dish is placed in the centre of the thaal and eight eager hands delve in simultaneously. And it is this unwonted sharing of jalebis and germs which most find hard to digest.

Uncomfortable though it may seem, however, this form of communal eating has long held this tiny community together. The approximately one million Bohras are descendants of Gujarati Hindu traders who, influenced by missionaries from Yemen, converted to Islam around the 10th century. Even today, in an age of increasing Islamisation, they have maintained their distinct identity and customs—often referring, without a smidgen of irony, to their brethren in prayer as “those Muslims”. Reluctant to be at the mercy of a temperamental moon, they follow a fixed calendar that ensures that their festivals arrive a day or two before those of the majority of Indian Muslims. Unwilling to don the stern black burqa, their women have adopted a frivolous, colourful version that reduces even formidable matrons to polka-dotted tea-cosies.

More than many Indian Muslims, the Bohras have retained customs from their Hindu past—an attitude that extends to their cuisine and results in extraordinary amalgamations. So chikoli is a sublime non-vegetarian version of dal-dhokli—a Gujarati comfort food in which squares of roti dough are simmered in a spicy dal. Khaloli jazzes up the dahi-and-besan kadhi with plump meatballs. While patrel biryani is achieved by cooking the very vegetarian patra—a popular Gujarati snack made out of colocasia leaves and besan—with mutton and spices.

These delicacies offer an important clue about the most essential ingredient of Bohra food—mutton. Admittedly, the cuisine boasts some unique vegetarian dishes—including a cold baingan bharta made with dahi and spring onion, and a sev ni tarkari in which bhel puri sev is cooked with onions. Not to mention the dish that surfaces whenever TamBrahm relatives-by-marriage are invited to dinner: khuddaal palida, a combination of rice and dal served with a flavourful concoction of dal water, drumsticks, bottle gourd and kokum. Moreover, a reluctant awareness of evils like cholesterol has forced chicken onto the menu, resulting in creations like chicken in a cashewnut or date sauce. But there can be no complete Bohra meal without mutton, a fact that woebegone gout victims and heart patients rue during dreary days of abstinence.

Not that everyday Bohra fare is unhealthy—if anything, it errs on the side of caution. The soupy mutton sarvas served with rice seem devised specifically for invalids with intestinal disorders; and the thicker tarkaris eaten with rotis wear a Diet Edition tag. But come festivals or ramzaan iftaar evenings and prudence is tossed into the wet-garbage bin along with eggshells. For at its most festive, Bohra food is a parade of deep-fried dishes, nutty gravies, fragrant pulaos and malai-rich desserts.

Although dominated by Gujarati and Mughlai techniques, these creations also boast exotic influences. From the bearded pheriwalas who wandered British India selling buttons and powders, to the modest businesses that traded overseas, Bohra merchants often returned from their travels with unfamiliar recipes and ingredients. Which explains why vintage Bohra cookbooks unabashedly include dishes like khaw suey, bride special macaroni bake and jelly souffle without acknowledging the copyright of the cultures that brought them onto the table.

My grandfather’s brothers were based either briefly or permanently in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Tokyo, while my grandmother was born in Penang and grew up in Singapore. So it seemed only fitting that platters of Karim’s spring rolls— overweight pancakes stuffed with a spicy kheema and fried to lacy perfection by Karim, the master cook—should arrive at the thaal between the kheer and khichda.

While such nouvelle creations are difficult to access, even traditional specialities like kari, a mutton curry with Indonesian overtones, often prove elusive. The couple of Bohra restaurants that tried to ride the trad-food fad downed their shutters soon after excited restaurant reviewers heralded their arrival. And the occasional five-star food festivals rarely venture beyond seekh kabab and biryani. The bhatiyaras—old-style caterers whose aromatic creations hurtle all over the city on handcarts—are gruff souls who scorn orders small enough to squeeze into a Mumbai apartment.

Which brings us back to square one—to sample a seven-course Bohra feast, you have to slip off your shoes and inhibitions, wield your soup-spoon as an instrument of offence and plonk down at a thaal. Be warned, however: once you’ve acquired the precious ‘Fatima weds Saifuddin’ invite, don’t take the easy option. Many a chicken-hearted soul has panicked at the thought of a sneezy, wheezy thaal companion and decided to avail of the offer extended by the father of the bride: “Don’t worry, there is going to be a buffet as well.” It will be much too late to rectify matters when you finally figure out that while you are munching generic butter chicken and gulab jamun, the masticating masses are attacking legs of lamb doused in an almond-and-yoghurt sauce.

Almost as elaborate as the wedding fare is the food served at jamans, large-scale dinner or lunch parties. These elaborate functions require the sort of precision planning more commonly associated with a rocket launch or IIT entrance exam. Well before the guests arrive, the requisite number of thaals are stacked in an invisible corner of the house, alongside rows of bowls filled with the salads, chaats, sauces and pickles that will ring the thaal. In the kitchen the distraught hostess flits around wondering why only five plates of gajar halva have been decorated with nuts and raisins when six thaals are to be served.

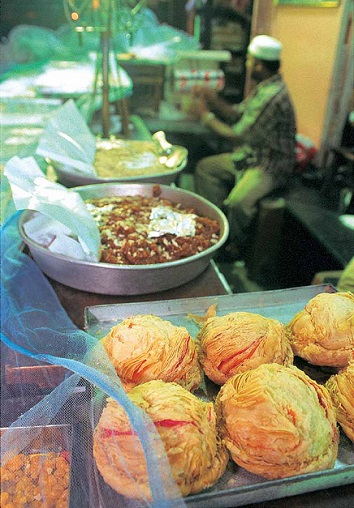

As a puddle of footwear forms near the main door, the bustle inside intensifies. While the guests sip on ultra-sweet sherbets or fruit punches, square mats are spread on the floor and weighed down with brass stands upon which the thaal will sit. This prompts a flurry of activity among guests who, at all costs, want to avoid the bores, bronchial patients and gluttons. Even more anxiously avoided are the food dictators—bossy women who, on behalf of the entire thaal, decline the plate of soft cream tikkas, morsels of pounded mutton skewered on wooden sticks and deep fried. Or send back the malai khaja, a flaky pastry stuffed with sweetened malai. “It’s much too heavy, we will never be able to finish it,” they coo, ignoring the glares of their neighbours. “But we wouldn’t mind more carrot salad.”

Once guests have taken their places, the thaals arrive in a solemn procession. Ignoring rules of conventional dining, the Bohras start their meal with a dessert—often a rich halwa. This is followed by fried or tandoored delicacies like kheema samosas, grilled chops or the now endangered brain cutlets.

Next comes another rich sweet—perhaps a warm khaja heaped with crumbly barfi or damido, made by cooking milk and nuts together. Surat is the home of sagla-bagla, a mithai topped with a pastry so light it can be consumed only if the fan is switched off. Mumbai hostesses who live dangerously place their orders with the famous Mohammedi Bakery in Surat and then torment railway inquiry till the precious cargo chugs into the city on the Flying Ranee a mere hour before their lunch do.

Tradition decrees that the hosts and their close relatives serve the guests, and by the time the second dessert is being devoured they are a hot and harried bunch. Often children are posted around the room to ensure that all the macaroni salad and mango chhunda bowls are full and to bring back critical reports like, “That third thaal has almost finished their khaja. But don’t give them more or there won’t be enough for us.”

The ‘mithas’ is followed by another ‘kharas’, something like a full chicken doused in a green, nutty sauce or a dabba gosh, marinated mutton topped with raw egg and cooked preferably on a coal sigri. Dishes like gakhar gosh—a spicy brown mutton served with a glorious, ghee-filled layered roti—are on their way out, but still make the occasional appearance. By this time, even the most oil-friendly souls need some respite—and this usually takes the refreshing shape of an ice-cream or fruit topped with whipped cream. Once the greedier thaals have polished off their second plate of figs and cream, it’s time for the rice dish, often a mutton pulao served with subtle soup, kari and rice or a dal with the mandatory mutton.

There are, of course innumerable variations to this theme. Some toss out the traditional dishes in favour of ‘fancy items’ like pasta bakes. A few sensible souls prune the courses—but most hostesses are determined to force-feed guests. More and more, after the rice dish has been consumed, the thaal is replaced with a clean one bearing a fruit sorbet, nuts, chocolates and paan—and, of course, the card of Bhol, Dilawar, Badri or whichever bhatiyara conjured up the meal.

Smaller parties are sometimes thrown to indulge particular food fetishes. Monsoon evenings often see ‘talans’ at which batches of bhajiyas—ranging from the conventional green chilli and onion to the unusual liver, brain and jaggery—are fried and served fresh to waiting guests. Summer get-togethers sometimes involve ras galas during which aam ras squeezed from different varieties of mangoes are served and volubly compared. While winter witnesses odiferous lasan lunches—during which shoots of tender garlic are chopped fine, mixed into a spicy kheema and topped with raw egg and sizzling hot ghee.

Those who encounter brain bhajiyas for the first time can be forgiven for wondering whether both the community and cuisine are hurtling towards extinction. But this concern is unnecessary. The Bohra community is hale, hearty and bustling with sprightly octogenarians. While the cuisine is gaining new groupies who, in the pursuit of a great meal, are willing to discard sense and sensibilities.

Where to get Bohra food in Mumbai

You might have bought a Malai Khaja from Tawakkal, or a gakhar from the garrulous, Sunday-morning vendor during a trip to Chor Bazaar. You might even have managed to find a contact number for Bhol or Dilavar or Ghoga — those monosyllabic caterers with utensils as big as houses — only to be put firmly in your place: “We do a minimum of 20 thaals and we are booked for four months.” But, by and large, until recently Bohra food was as difficult to source as reindeer meat.

Then along came The Bohri Kitchen in 2014 – and suddenly the sumptuous cuisine was available, not just for love, but also for money. The Bohri food boom began when Munaf Kapadia started serving a traditional feast cooked by his mother in his simple Colaba apartment. The experimental Saturday and Sunday lunches proved so popular that Kapadia quit his job with Google to deal with the drooly demand. Kapadia, has now started a home delivery service as well. “My mission is to take Bohri food to non-Bohris and to set up kitchens across the country. I want to make it as well-known as Lebanese or Continental food.”

Kapadia is not the only entrepreneur to understand the pull of hand-churned custard apple ice cream. In 2015 The Mighty Bohri Thaal, too, has spread its mat. As has The Big Spread in Byculla. And so visible has the cuisine become that the blog Brown Paper Bag felt compelled to wonder, “Is Bohri the new black?”

There is startling absence of vegetarian options. Admittedly, there are many pretty salads – the sorts that sit in little bowls along the rim of the thaal and provide the happy illusion of a balanced diet. There’s also the delicious khuddaal palidu – a dal, rice and drumstick dish eaten with a cold, yogurty baingan bharta. And, there’s a strange but addictive bhaji made out of sev and spring onion, and usually eaten alongside aamras. And then…well…a bunch of ho-hum, generic veggie dishes that hardly deserved space in either a cookbook or a feast.

The biggest stumbling block in the path of universal approval was, however, the extraordinary way in which Bohra food is served. The traditional feast is eaten on a round metal plate, bigger than a hoola hoop. About 80 hungry souls sit around each thaal. Then the hosts and their army of helpers march into the room with huge bowls of Peaches and Cream or Mango Mousse. Each thaal gets one bowl. And in a tremendous clatter of spoons and enthusiasm, everyone lunges and plunges and critiques.

The first dessert is followed by a starter. Crisp kheema (qeema) samosas. Or chicken-white sauce cutlets. Or even, on a really lucky day, bheja cutlets. Then comes a halwa glistening with ghee or a warm malai khaja topped with rose petals. Then the kharas or the main dish – a nice golden dabba gosht, or a full tandoori chicken or, of course, a raan that has been marinated overnight and then roasted to tender perfection. After which another dessert – often a fancy confection or sorbet – provides a light interlude before the sumptuous rice dish.

So, how have the purveyors of patrel biryani and doodhi halwa managed to navigate these obstacles?

With clever packaging, editing and a National Geographic-style patter that makes guests feel that they are part of a cultural safari. At The Bohri Kitchen, the thaal is placed on a table rather than on the floor. Individual plates and cutlery are provided and sharing is kept to a minimum. Hosts provide commentaries about why each meal starts with a pinch of salt, how the kheema samosa must be cracked and squirted with lime, and provide a potted history of the Bohra community.

Clearly, this strategy works. For the time being, at least, Mutton Soup cooked with Cashews and Milk and crumbly Gol Papri made with jaggery and wheat flour are the flavours of food adventures.

Recipes

I

Excerpted by Shabnam Minwalla, from Bohra recipes, published by Inquilab | Indian Express

Lagan ni Seekh

Ingredients

1/4kg – Minced mutton

2 tsp – Ginger-garlic paste

1/2 tsp – Green chilli

1/4 cup – Coriander leaves

1/4 cup – Mint leaves

2 – potatoes, grated

4 – eggs

2 – bread slices, soaked

2 tsp – Oil

1 – tomato

Salt – To taste

Method

- Add all the masala in the minced mutton.

- Beat 1 egg and mix in the minced mutton and keep aside for 30 minutes.

- Cut the tomato into slices.

- Set minced mutton in a tray and garnish it with tomato slice.

- Beat the remaining eggs and pour on the minced mutton.

- Heat oil and pour on the eggs.

- Close the lid and cook in the oven at 180 degrees C for 20 minutes.

Paya Keema Khichdi

Ingredients

1/2kg – Paya

2 tsp – Ginger garlic paste

3 – Onions, chopped

1/2kg – Keema

1 tsp – Ginger-garlic paste

2 tsp – Red chilli paste

1/2kg – Rice, half-cooked

1/2kg – Tur dal, half-cooked

2 – Potatoes

2 – Boiled eggs

3 tbsp – Oil

3 tsp – Wheat flour

1/2 cup – Coriander leaves

1/2 cup – Mint leaves

1-2 – Bay leaves

1 tbsp – Cumin seeds

Method

- In 1 tbsp oil, sauté ginger garlic paste and some of the chopped onion until they turn brown, add the paya and cook for half an hour.

- In a separate vessel, add a tbsp of oil, add the ginger garlic paste and keema.

- Add the red chilli powder after 10 minutes. Cook for another five minutes.

- In another vessel, fry the rest of the onion until it becomes pink. Add spices, red chilli powder, turmeric, coriander and wheat flour.

- Add the paya and cook for 15-20 minutes.

- For the khichdi, mix dal and rice and keep aside.

- Fry chopped potatoes and keep aside.

- Add coriander leaves, mint leaves, eggs and potatoes and mix everything with the keema.

- Season with cumin seed and bay leaves.

- In another vessel, make layers of khichdi and keema and cook for 15 minutes. Serve khichdi with paya.

II

Dal chaawal and palidu

Serves 3

Ingredients

For dal chaawal

1 cup split pigeon peas (toor dal)

½ tsp turmeric

Salt to taste

1½ cup rice

2 cups water

For palidu

200g bottle gourd or 2 drumsticks cut into 4 pieces each

I medium tomato, chopped

2 tbsp wheat flour

2-3 kokum (Garcinia indica)

½ tbsp fenugreek seeds

¾ tsp red chilli powder

½ tsp coriander and cumin powder

½ tsp cuminm seeds

½ inch stick cinnamon

3 cloves

6-7 curry leaves

1 onion, sliced in thin rings

150g cooked mince (optional)

1 tbsp garlic paste

3 tbsp refined oil

Method

1 Pressure-cook the pulses (dal) with turmeric and salt until about 75 per cent done. Strain and add tomato and drumsticks/gourd, kokum, red chilli powder and coriander and cumin powder to the residual water, and keep aside for palidu.

2 Heat half the refined oil in another vessel and add cumin, cinnamon, cloves and the curry leaves. Follow it up with onion and sauté until it turns brown.

3 Add the cooked dal to this vessel. Stir and add the mince, if using.

4 Cook rice (chaawal) in another vessel until about 75 per cent done.

5 Put the rest of the refined oil in another vessel and add fenugreek seeds and garlic paste and sauté for a minute. Mix in the wheat flour, sauté for two minutes and add the residual dal water to it. Keep covered on heat until the vegetables are cooked. The palidu is ready.

6 To serve, place a layer of dal in a vessel and cover it up with the rice. Follow with two more such layers and end with a final layer of rice. Garnish with coriander and eat it with palidu.