Bhavnagar State census: Distribution And Movement Of The Population

This article has been extracted from DELHI: MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS |

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Invariably, some words get garbled during Optical Recognition. Besides, paragraphs get rearranged or omitted and/ or footnotes get inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. As an unfunded, volunteer effort we cannot do better than this.

Readers who spot errors in this article and want to aid our efforts might like to copy the somewhat garbled text of this series of articles on an MS Word (or other word processing) file, correct the mistakes and send the corrected file to our Facebook page [Indpaedia.com]

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

Distribution And Movement Of The Population

The territories of the State of Bha vnagar lie at the head and west side or the Gulf of Cambay in the Peninsula of Kathiawar, though a few outlying villages are situated in the Dhandhuka Taluka of the Ahmedabad Collectorate. The State does not present a compact appearance, interspersed as it is with the foreign territories of the States of Palitana and Wala, and the British Taluka of Gogha. This is due to the historical antecedents of the State which have mainly contributed to the raising of the small Gohel principality of Sihorinto the present State of Bhavnagar, by additions made to it from time to time by the brave and_ enterprising predecessors of the present ruler. The anarchy and misrule prevalent on the eve of the dissolution of the Great Mughal Empire fired Bhavsinhji I with an ambition to secure a suitable venue for the extension of his existing kingdom, and found the present capital of Bhavnagar in the year 1723. At that time the British had already appeared on the scene, and the hold of the Peshwa and the Gaekwar on Saurashtra was loosening. The time that followed proved greatly opportune for the realisation by Wakhatsinhji and Wajesinhji of the dream of the modem Bhavnagar cherished by Bhavsinhji I. They extended and consolidated their kingdom and brought it to its present dimensions, by defeating the neighbouring chiefs and subduing the turbulent Khasias and Khuman Kathiswhose territories they conquered. Since then the area of the State has undergone very little change of noticeable importance. _ 2. Area and Boundaries.-The State lies between 21"18' and 22'18'north latitude and 71°15' and 72°18' east longitude. It has been cadastrally surveyed, and according to the Revision Survey recently completed, the total area of the State is recorded to be 2,961 square miles which shows -an increase of 101 square miles upon the area as shown.,.at the last Census. The Bhavnagar State. is bounded on the north by the Ranpur parganah under the Ahmedabad Dlstnct and by the Jhalawar and Paneha! Sub-divisions of the Peninsula' on thesouth by the Arabian Sea; on the east by the Gulf of Cam bay and a po;tion of the Dhandhuka Taluka; and on the west by the Sorath Kathiawar and Halar sub-divisions. The Separate Jurisdiction villages are al~ scattered over the territory of the State.

- 2 CHAPTER I-DISTRIBUTION AND MOVEMENT OF THE POPULATION

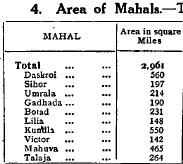

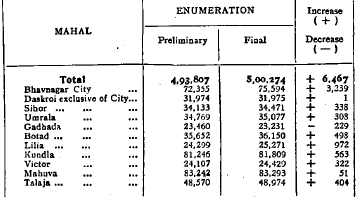

3. Administrative DivisioDS.-For the purposes of revenue administration, this State is divided into two Divisions, 'Viz., Northern and Southern, each •comprising of five Mahals or districts. The Mahals are further sub-divided into Tappas which are groups of villages of convenient size. The Mahals of Daskroi, .Sihor, Botad, Gadhada, and U mrala constitute the Northern, and those of Lilia, Kundla, Victor, Mahuva, and Talaja the Southern Division of the State. As far back as 1881, the State consisted of nine Mahals only, when the Mahal of Victor was for the first time brought into being and constituted into a separate Mahal, 'with the Rajula and Dungar Tappas of the Mahuva Mahal. Another important •change was the transfer in 1918 of the twelve villages of Daskroi to the Mahal of Talaja, which with the addition of other few villages of the latter Mahal formed under it the separate Tappa of Trapaj. A new Tappa of Bhandaria was consti• tuted in the place of the Trapaj Tappa thus transferred to Talaja by taking a few villages of the old Trapaj Tappa and some others from. the Bhumbhali Tappa. In the year 1923, the villages of Rajapara and Sakhadasar of the Daskroi Mahal 'were also transferred to the Trapaj Tappa of the Talaja Mahal. The changes thus effected from time to time have had a corresponding effect upon the area and population of the Mahals and Tappas concerned. Adjustments have, there• fore, been made in the figures of population of the preceding Censuses as' shown in Imperial Tables II and XX and State Table I on the basis of the area, as it 'stood on the 26th February 1931. As has been already noticed in the Introduction, a significant departure has been made from the practice of the previous 'Censuses of giving figures only for the State as a whole in that a special recogni. tion has been accorded to the City of Bhavnagar and also to the Mahals in •certain iinportant tables where they have been taken as a unit. 4. Area of Mahals.-The marginal table gives the figures of area of the ten Mahals of the State. From the point of area, the Mahal of Daskroi enjoys the first place with an area of 560 square miles. Next come the Mahals of Kundla and Mahuva whose respective areas are 550 and 465 square miles j Lilia and Victor are the smallest of the State Mahals, and have an area of 148 and 142 square miles respectively •

divided a State or Province into Natural Divisions consisting of tracts in which the

'natural features are more or less homogeneous .. Such an attempt in the case of

.-a State of the size of Bhavnagar is hardly of any practical utility. Bhavnagar

'State itself forms a part of a greater natural division of the country styled as

Kathiawar. Be~ides, the advantage of having natural divisions has been more

-than once questIoned, as in actual practice the figures are more particularly

required by administrative divisions rather than by natural divisions. Divisions

'of this kind ate hardly scientific and are still less suited to a comparatively smaller

'state as this. '. Such an attempt has, therefore, been abandoned. It may,

however, be noted here that in dealing with larger areas, the scheme must be

regarded to possess some value where people are bound together by ties of language

and sentiment. Natural divisions are also useful in explaining the variation in

.density at different places resulting from the differences of climate, rainfall, and

.soil. But in the case of the Bhavnagar State where the differences of language

. and sentiment are non-existent, and where the divergence in climate and soil is

not very great except in a few places, the creation of natura.l divisions should

'-Safely be dropped. An attempt in this direction will, however, suggest the divi.

sion of the State into the Kharopat, Kanthal Non-Kanthal and Bhal. The

Kharopat will include the Mahal of Lilia, and the Jira and Kundla Tappas of the

Kundla Mahalj whereas the Kanthal will include the Coastal Mahals of Mahuva

.and Talaja, and some portion of the Daskroi Mahal. The Bhal will be a

,separate division by itself owing to its physical peculiarities. The remainder

.portion of land may be conveniently called the Non.Kanthal ..

6. Definition of .. Population."-Before undertaking a statistical an.alysis.

of the fii,'lJres of population as .returned by the .Census, a.clear understandmg of

the term • population' as used In the Census hterature IS necessary. By. thepopulation

of the Bhavnagar State is meant all pe.rsoos.en!lmerated on th~ DI~ht

of the 26th February 1931, as being present and ahve within th~ State te!n~or1es,

persons travelling by railway and enumerated at the stati~os SItuated wlthm the•

boundary of the State and persons on board the vessels In Bhavnagar watersincluding

those for ~hom the schedules were received from the Port Supervisor

upto the 15th March 1931. The aggregate of the population thus recorded is the

actual or de facto population of the State ~ ?istinguished from its. ~e jur~ C?r

normal resident population. The former will mclude ~rsons not resl~mg wlthm

the State territories and exclude some of the normal residents who will be enu••

merated outside the State.

The Indian Census is a synchronous Census, and aims at enumerating: all the persons wherever found at a particular time on a particular day. The• hours between 7 p. m. and midnight have been conveniently chosen for the' purpose. Every precaution is taken to enumerate all living human beings,. wherever found, whether in houses numbered for the purpose, or• outside the houses on roads, railways,steamers, as well as the vagrants in the streets for whose enumeration special arrangements are made. By a judicious selection of the• Census Night, the least possible fluctuation in 'the movement of population is. secured. In India, the month of February or March corresponding to the Hindu month of Falgun is generally selected. For, it is the part of the year when nogreat assemblages and religious fairs are held, and celebration of marriages is. prohibited among the Hindus.

The de jure population is the population normally residing in a locality~. In India, the population as recorded at the preliminary enumeration will roughly supply figures of the de jure population of the State. For, only the population. living in houses which correspond to so many' commensal families' is enumerated' at the first count which takes no notice of the tempbtary sojourners and the travelling public.

The basis of clasSification of population differs in different countries~ England and France have the same basis of classification as India. What is. called de facto in India is in France known as II la population de fait". Popula. tion de jllre is equivalent to II la population de droit" which includes all persons usually resident in an area including those temporarily absent, and excluding those only momentarily present. There is' also a third division, viz., lila popula. tion municipale" which the French. have adopted. It means II la population de droit" minus prisoners, hospital patients, scholars, residents in schools, members. of convents, the army and so on. The United States of America have a threefold classification, viz., the II Constitutional population" which excludes residents in Indian Reservations, the Territories and the District of Columbia' the II general' population" which includes in addition the territories' and the ~. total population," which includes all excluded in the former.' • A synchronou.s Ce~sus with !ts double classification of the population intI> dll la~to and de JU~6 IS ~t SUited to Indian conditions for its simplicity in enumerattng the people mhablting such a vast continent.

7. ~ccuracy of Census Figures.-Mter this preliminary discussion as. to the meantng of the term 'population' some estimate of the degree of accuracy of the. Censu~ figures may well be made. Doubts are not unfrequently expressed regardtng their correctness ~nd accuracy. In such a complex business as the. Censl;ls. absol?te accu~cy IS to be found nowhere in this world. It must always. remrun as an Ideal w.hl.ch eyery Census worker should try his best to attain with. 0!l~ completely attammg It. Because an ideal Census presupposes that every ~Itizen of the State understands his civic responsibility and will try to see that he IS properly enumerated. On the other hand, every Census official will , in hi!> 1. Prof. Bowley, B~n" oj Stah~tics. p.25.

turn, fulfil bis duty, and leave no stone unturned to' secure this state of ideal perfection. But as human nature varies from place to place and from one individual, to another, this is never to be hoped for. Errors and omissions are, therefore, bound to occur. Cases of persons left out from enumeration as also of persons enumerated twice over, not to talk of the cases of inexact entries, will always occur. But this is inevitable and cannot be helped. \Vhat is, therefore, necessary is to take such precautions and devise such safeguards as will reduce the resulting mistakes to a minimum. The extent to which they are put into practice will determine the degree of accuracy achieved. So far as the present Census is concerned it may with all modesty be asserted that both from the point of numbers and details, it is better placed than any of its predecessors. And this opinion has been shared by not a few responsible State officials and public men who have been kind enough to point out the comparative superiority of the present Census. Various factors have contributed to this success. , Deterrent punishment of the indolent workers coupled with substantial encouragement given to the deserving in the shape of cash rewards to the extent of nearly Rs. 1,500 had a very wholesome effect in improving the existing machinery of enumeration. It put the workers on their mettle and induced them to show better work. Proper instructions supplemented by exten' sive checking and inspection exercised by the supervising Census oflicials greatly improved the recording of the entries in the enumeration books. It must, however, be admitted that there must have been persons who will not have been enumerated at all and who must be offset against those enumerated twice. The resulting error will indeed be very small, almost negligible, as it is spread over large numbers. So from the point of numbers, the present Census may be credited with the fairest degree of accuracy without the slightest hesitation. Omissions are likely to occur in the case of the public travelling by rail and steamer. And they will vary from station to station according to the arrangements made to enumerate the passengers at the platform, and on the running trains, and vessels in the harbour. It is unnecessary to enter here into useless details about the precautions taken in this behalf, and already mentioned in the Administrative Report. Suffice it, therefore, to say that the hearty co•operation of the Railway authorities was of great help in eliminating all probable errors which can be judged from the fact that as many as 1,752 persons were enumerated on the railway platforms, running trains, and boats. From the point of details, this Census has' been more comprehensive than any of its predecessors. And yet there is left much to be desired by way of making the entries recorded perfect, especially in entering the details regarding the occupational columns which is the stumbling block of the Census in almost all the countries of the world. Some of the important details are, therefore, lacking, -leaving ample scope for the intelligent guesses of the Abstraction Office. But this ,can be only remedied by a proper understanding of the scheme of enumeration which cannot be ensured so long as the great mass of the people is uneducated ' and the available enumerators in rural areas are not sufficiently trained. Any short-coming, therefore, that is likely to manifest itself will be rather in the direction of under•estimation than that of over-estimation. Attention will, from time to time, be invited to the value to be attached to the various sets of figures at the commencement of each Chapter. There is, however, one point of great significance about the Census figures ,of 1931. The No-tax campaign and the Civil Disobedience Movement started by Mr. Gandhi on the 12th March 1930 were going on in British India, until the Delhi Pact was signed on the 5th March 1931. The multifarious boycott activities -ofthe Indian National Congres saw in the Census a fresh venue for obstructing the Government. The Census officials in some places in British India were handicapped in their work by the refusal of some persons to volunteer the information required to be entered in the schedules. But fortunately that was not the -case with the Indian States. The Census returns of this State are, therefore, wholly unaffected' by the boycott movement. One stray case of refusing' AN ESTIMATE OF THE NORMAL POpULATION 5 information, however, occurred in the City of Bhavnagar, but such an exception goes to prove the general success of the present Census. 8. An Estimate of the Normal PopulatioD.-The total or actual population of the State as registered at the, present Census is 5,00,274 persons of which 2,57,156 are males and 2,43,118 females. T~e enumeration books record places of birth, but not the places of normal residence, and therefore, afford no clue to the normal resident population of the State. But an estimate of the normal population as distinguished from ~he. total popula~on recorded on the Census Night can be had from the prehmmary enumeration. Because the latter takes notice only of the permanent population living in houses situated within a locality. The running and floating population and the outsiders who are in the State at the time of the preliminary enumeration are not entered in the schedules. The preliminary enumeration which records only the de jure population may be regarded to make a closer approximation to the normal resident population of the State which comes to 4,93,807 persons of which 2,54,598 are malcs and 2 39,209 females. The figures on the margin show the difference between thc two' sets of figures, and represent 'the fluctuation in the population during the interim period. Out of a total increase of 6,467 persons, as many as 3,239 are absorbed by the City of Bhavnagar. Apart from its urban characteristic the temporary flow of immigration to the ,capital of the State at the works going on in connection with the Investiture MAHAL Total

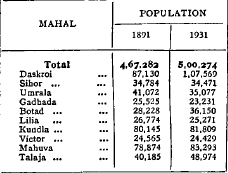

of His Highness the Maharaja Saheb is in no small degree responsible for the swelling of the City population. Fluctuations are more frequent in urban than in rural areas; and this will be seen from an increase of only one person in the preli!"ina~y populatio~ of the Daskroi Mahal excluding. the City of Bhavnagar. But 10 thiS as well as In nearly all the other Mahals the Increase is partially due to the return home of some of the normal residents from the neighbouring States where they.had gone out on wedding parties at the time when the preliminary record was m progress. The solitary exception to this rule of increase is furnished by the Gadhada Mahal where the same cause seems to have operated in an opposite direction. I 9. Area and Population.-The present Census registers a total of MAHAL

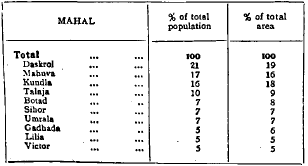

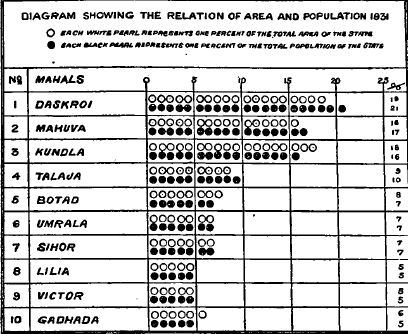

5,00,274 souls. The marginal table shows the figures of percentage distribution of area and population of the State in each of its ten Mahals' arranged in order of, magnitude. A diagram showing the relation between the area and population of the Mahals is also given "below. Each white pearl represents one per.; th Stat d h ,cent. of the total area of e e, an eac black pearl represents one per cent. of the total population. "

10. More than half the area and population of the State are contained. in the MalIals of Daskroi, Kundla, and Mahuva. More than 15 per cent. of the total population live in the City of Bhavnagar including which the Mahal of Daskroi appropriates to itself 21 per cent. of the total population. The Mahals of Kundla and Mahuva have respectively 16 and 17; Talaja 10; Botad, Umra1a~ and Sihor each 7; and Lilia and Victor each 5 per cent. of the total population. No great divergence between the percentage distribution of area and population of the Mahals is noticed; and they follow practically the same order with this difference that from the point of area Kundla takes precedence over Mahuva. The Mahals of the State with the exception of Daskroi and Talaja can be con• veniently arranged in three groups of three sizes each having Mahals with very nearly the same area and population. MalIuva and Kundla each with nearly 17 per cent. of the total area and population will fall in the !Jrst group; Botad,. Sihor and Umrala with 7 per cent. in the second; and Gadbada with 6 and . Lili<J. and Victor each with 5 in the third

MOVEMENT OF THE POPULATION

11. Meaning of Movement.-By the movement of population is meant the changes in the population of a unit area of land from Census to Census. The term movement is not used, in the sense of physical movement denoting the migration of people from one place to another and 'CIice versa. The latter 'will; however, form the subject matter of a later chapter relating to Birth, place.•

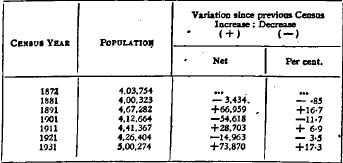

12. Changes Since 1872.-The first synchronous Census of the Bhavnagar State was taken with the first Imperial Census in 1872. The marginal table illustrates that the history of the Bhavnagar State Census has been one of alternate increase and decrease in its population. The 1891, 1911, and 1931 'Censu~ are the Censuses of increase, whereas those of 1881, 1901, and 1921 •are the Censuses of decrease in the State pgpulation. The movement of THE PERIOD 1812-1911 7 population has been more or less uniform throughont all the MahaIs of the State. With some minor exceptions, an increase or decrease in the population of the State has been invariably accom• panied by a correspondi ng increase or .decrease in the popu• lation of its Mahala.

13. The popu• 1931 5.00,274 +73.870 +17•3 lation of the State of Bhavnagar as it stood at the commencement of the Census era, i.e., in 1872 was 4,03,754 persons of which 2 13 57l were males and 1,90,183 females. With the periods of alternate rise and' fa'IJ it has at the present Census stood at 5,00,274, giving a net increase of '96 520 persons or 23'9 per cent. during the last 59 years. Taking the figures for 'the last fifty years, the rise is nearly one lac or 25 per cent. There has thus been an average increase of 16,000 souls or 4 per cent. from -Census to Census.

14. The Period 1872-1911.-The movement of the population of the -State will now be considered in the light of the conditions prevailing during the period 1872-1911. It may be asked: to wbat then is the variation in the popula. tion of an area due? It results from the natural growth or otherwise of the population by an increase or decrease of births over deaths which is due to various causes i from a favourable or unfavourable balance due to an excess or deficit of immigrants over emigrants i from better enumeration i and lastly from changes in its boundaries. As regards the last mentionetl' factor, it may be briefly stated that since the inception of the Census era, there has been very little change in the boundaries of the State involving an increase or decrease in its population. They have practically remained the same, the Revision Survey being responsible for an increase of 101 square miles in its area. Regarding the accuracy of enumeration, it may be noted that the first two Censuses of 1872 and 1881 must have suffered from want of proper enumeration, as the complex machinery of the Census in its present form was for the first time then set up in the State. and also because the people being new to the Census idea may not have intelli. gently co-operated in, if not actually opposed to the Census operations. Some time must have. therefore. elapsed before it got into perfect working order. The records of these two Censuses must have naturally suffered, as in the case of the rest of India, from under•enumeration. But since the Census Report of the State comes to be written for the first time on this occasion, it is hardly possible to dip into the past to gauge the extent of this affection. By 1891, as elsewhere, this State also got used to the working of the Census machinery i and as will be seen from the returns of that year, omissions were reduced to a minimum.

15. The rise and fall in the State population and their causes wil( now' be discussed. The decrease of -85 per cent. revealed at the Census of .1881 was due to the famine of 1878. 'But the decade 1881-91 was a period of rapid rise . and recovery. It has been generally observed that birth•rate rises rapidly after a period of heavy mortality due to war, disease or famine. Famine mortality is high among the very young and the very old; and so when a period of famine is followed by ~)De ~f plentiful rai!lfall an~ good crops as was~ case during 1881.91, the populatIOn IDcre~ses rapidly owmg to an unusu~lly high proportion of persons at reproductive ages. The movement of population received a great . momentum aDd registered an increase of 16•7 per cent. in 1891 upon the popula8 CHAPTER I-DISTRIBUTION AND MOVEMENT OF THE POPULA nON tion as returned in 1881 (4,00,323). The increase was alround. The solitary exception to this tendency was, however, noticeable in the Mahal of Botad which recorded a decrease of 1,714 persons. But this decline is not at all convincina at a time when the whole of the State in general, and each of its Mahals in particular showed. such an extraordinary onward movement. It can be attributed only to inaccuracy in enumeration. No other intercensal period except the present registers such a high percentage of increase in the State population. The truth of this remark is horne out by examining the comparative figures of the population of the Mahals as it stood in 1891 and 1931. The marginal statement illustrates the unprecedented character of the 1891 Census, and points out• that even with the impetus given to the growth of numbers during the last intercensal period, the Mahals of Sihor and Victor have with difficulty succeeded in attaining their 1891 level, whereas the Mahals of Gadhada, U mrala, and Lilia are still lagging behind. But this spell of prosperity did not last long. On the close of the decennium that followed the Census of 1891, the Great Famine of 1900 popu-

. larly known as the 'Chhapania,' notorious for the intense misery and irreparable loss it caused to' humanity made its appearance. It came as a great calamity and laid low the whole mass of population. History seems to repeat itself in every sphere of human life, and . a period of heavy decrease followed a period of heavy increase. There was a decrease in the popUlation of all the Mahals of the State without a single exception. An increase of 16'6 per cent. was followed by a decrease of nearly 12 per cent. But much of the ground lost in 1901 was recovered at the Census of 1911, owing to the favourable aaricultural conditions which prevailed during the greater part of the dece~nium that followed the Big Famine. The damage that was wrought was indeed far too widespread and intense for the loss and suffering involved to be made up during the course of a single decade. Yet nearly half the loss sustained in 1900 was recuperated notwithstanding the ravages of plague which continued in milder' form from 1905 to 1908, and a rise of 6'9 per cent. was the result. But this rise was absent in the Mahal of Sihor which showed a negligible decrease of 232 souls.

16. Condition of the Period 1911-21.-The Census of 1921 pre• cedes the decennium which is the subject matter of this Report,and should, therefore, be reviewed in some detail. It is the Census of decreasing returns, and registers a fall of 3'5 per cent. or 14,963 souls in the population of the State as it stood in 1911. Much of the progress made at the last Census was set at naught by the combined effects of a famine followed by plague and influenza epidemics. But they have not affected the Mahal of Talaja and the flourishing. Mahal of Botad which seem to have resolved to make up for their past arrears. All seemed to go on well upto the year 1917, and the natural population was increasing under the influence of favourable agricultural and economic conditions. But suddenly the failure of crops was followed by plague, and before it had disappeared, the monster of influenza raised its head, sweeping away a large number of the population of reproductive ages. Both these pests exacted a heavy toll all over the State, and were mainly responsible for the reduction of population. There were other contributory causes also. It was a period of great panic and uneasiness. The World 'War was raging on the European battle-fields from 1914-19. The prices had gone enormously high; years were lean; and living had become dear. These then were not the times which would encourage any growth of population. To this should be added the effect of the• migratory currents set into motion by the great impetus given by the war to the,

Indian trade and commerce. The artificial prosperity of the war time that had seized the Indian trading and commercial centres and the boom period that followed it, attracted the enterprising Bhavnagaris to the cities like Bombay and Ahmedabad. This outward flow of the State population accounts to no mean degree for the decline in the movement of population noticed in 192].

THE PAST DECENNIUM 1921-30

17. Changes prior to 1921 have been disposed of. The agricultural, industrial, and the general physical conditions obtaining during the decade under report will now be dealt with, in order that some idea can be had of the causes that have promoted the growth of numbers during the past ten years.

18. Condition of Agriculture.-A description of the agricultural condition during the past decennium must involve a discussion of the physical condition and other problems that directly influence the extension, development and normal progress of the cultivation of the soil, as also of the incidents that in. directly contribute to the well.being and amelioration of the agriculturist by improving and bettering his economic condition. Among the first will be considered such questions as the land under cultivation, proportion of cultivat. ed land to cultivable land, land under irrigation, the proportion of land onder different kinds of crops, and rainfall. Among the second will be considered the effects of such measures as credit c().()perative societies, and the Khedut Debt Redemption Scheme.

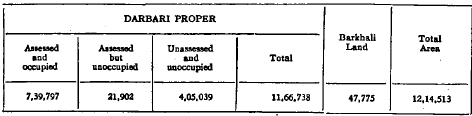

19. Land under Cultivation.-With a negligible variation the lanel under cultivation during 1921-31 practically remained the same. A slight increase during 1925, raised the acreage for that year to 7,40,219. The following are the figures of Darbari proper and Barkhali land in acres' for the year 1930:- .

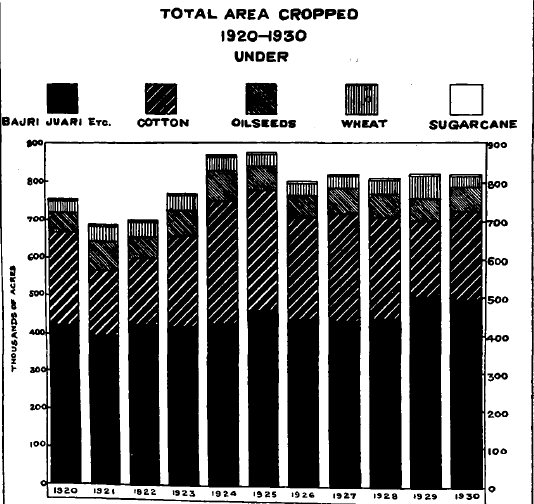

20. Crops.-The Subsidiary Table gives figures of the mean density

per square mile of the total and cultivable area. The percen~es of cultivable

. and net cultivated area to the total are also shown. By gross cultivated'

pr total area sown or cropped is meant the net cultivated land plus the area

which is do.uble cropped. Thus by adding 7,796 acres which are double cropped

to 8,12,322 of netcultivated area, the figure of8, 20,118 acres under gross

cultivation is arrived. By' net cultivated' area is meant the gross cultivated

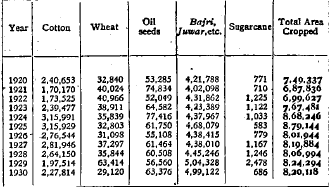

area minus the double cropped. During the year 1930, bajri, juwar and

other staple food stuffs were grown in 61 per cent. of the gross cultivated

area. Of the other produce, cotton came highest with 27 per cent., whereas

oilseeds, wheat and sugarcane were sown in 8, 4 and '1 per cent. of the total

cultivated area. Food stuffs daimed the highest percentage of the total sown

. area j and cotton more than one-fourth. But in the years 1924 and 1925 the

latter appropriated 36 per cent. of the total area under gross cultivation on

account of the high prices of cotton then ruling the market. At the commencement

of the decade, i.e., in 1921 cotton was grown in 1,70,170 acres, but the rising

tide of prices in 1922 increased the area in 1923 to 2,39,477 acres, which further

expanded to 3,15,991 and 3,15,929 acres in 1924 and 1925 respectively. But

with the fall in prices in 1926, it again fell to 2,76,544 acres and as low as

1,97,514 in 1929, when the prices were barely sufficient to cover the expenses of

-cultivation and leave a very narrow margin of profit. The marginal table gives

the figures in acres of different kinds of crops sown from 1920-1930. Food stuffs have been increasiguly sown during 1929 and 1930. The area under wheat cultivation was at its highest in 1929, and with bajri and ju'War . claimed 68-8 per cent, of the gross cultivated area. Area under oilseeds and sugarcane showed slight fluctua- . tions, in response to the rise in prices, by showing an increase in the area sown. During the decade, the total area sown including the double cropped has shown a steady rise. From 6,87,836 acres in 1921 it has come upto 8,20,118 acres in 1930, and in 1924 and ~925 when the prices ruled highest it went up to 8,68,246 .and 8,79,144 acres respectively. The effect of a rise in the level of prices is seen from the increasing area of laNd thus brought under cultivation. The diagram opposite illustrates the variation in the gross cultivated area, and the area under the different kinds of crops from year to year.

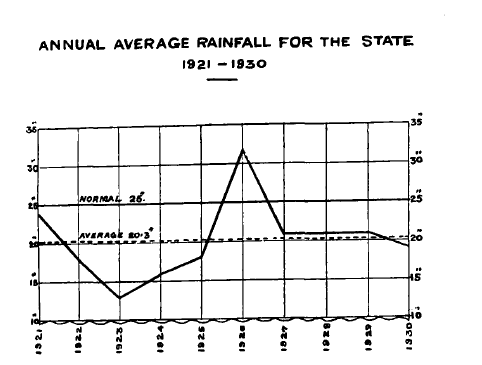

21. Rainfall.-.' Rainfall has much• fo •dO willi determining the agricultural

-condition during the intercensal period. Many other factors as prices, market and

freedom from pests like locusts also enter into the successful termination of an

agricultural season. The Subsidiary Table VII at the end of the Chapter gives

the figures cif rainfall in the Mahals of the State since the year 1885.. Figures

•of . average rainfall for 35 and 45 years from 1885, as also for the past decade

are :also shown. In the curve on the opposite page are plotted for the State

the figures of annual average rainfall in inches for 1921-30; the lines of

normal rainfall and average decennial rainfall areaIso plotted. It is hardly

necessary 'to emphasize the uncertain• and erratic nature of the monsoon

in. the State., . The. vagaries of the Indian monsoon :are too well-known

to be mentioned. It should be only pointed out that a high average does not

necessarily suggest a successful season, nor a low average a lean year. What

.teally counts in India is not the average amount of rainfall in a particular locality,