Bhagat Singh, freedom fighter

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Lesser known stories

Devyani Mohan, March 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: Devyani Mohan, March 23, 2018: The Times of India

Revolutionary freedom fighter Bhagat Singh, along with comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev, was hanged on March 23, 1931. The revolutionary freedom fighter was only 23 years old. His death inspired hundreds to take up the cause of the freedom movement. His ideology continues to be relevant even in the context of today's social and political situation.

Thirst for books was legendary

The October revolution led by the Bolsheviks and Vladimir Lenin that led to the larger Russian Revolution of 1917 attracted Bhagat Singh and he started to read literature about socialism and socialist revolution at an early age. M M Juneja, who has written two books on Bhagat Singh, noted how his love for reading continued till the very end. In an article for TOI, Juneja wrote,”One of his co-prisoners at the Lahore Central Jail, Shiv Verma said ‘Though we all had a passion for reading, Bhagat Singh was a class by himself. Despite having a soft corner for socialism, he always clung to his passion for reading novels, particularly with political and economic themes. Dickens, Upton Sinclair, Hall Cane, Victor Hugo, Maxim Gorky, Stepnik, Oscar Wilde and Leonard Andrew were among his favourites. He frequently got emotionally involved with some particular characters in novels, to the extent that he wept and laughed with them.’"

M M Juneja went on to say, “According to some estimates, he read nearly 50 books during his schooling (1913-21), about 200 from his college days to the day of his arrest in 1921, and, approximately 300 during his imprisonment of 716 days from April 8, 1929, to March 23, 1931. He was exactly 23 years, five months and 25 days old at the time of his execution, and had by then had studied hundred of books — a record of sorts.”

This passion for reading endured till the very end. M M Juneja narrated the following incident. “Pran Mehta, Bhagat Singh's lawyer was allowed to meet him on March 23, 1931, just a few hours before the hanging. Bhagat Singh was then pacing up and down in the condemned-cell like a lion in a cage. He welcomed Mehta with a broad smile and asked him whether he had brought him Vladimir Lenin's book, ‘State and Revolution’. As soon as he was handed the book, Bhagat Singh began reading it as if he was conscious that he did not have much time left. Soon after Mehta's departure, Bhagat Singh was told that the time of hanging had been advanced by 11 hours. By then, he had finished only a few pages of the book.”

Manmathnath Gupta, a close associate of Bhagat Singh also recalled those final moments, which Juneja mentioned in his TOI article. "When called upon to mount the scaffold, Bhagat Singh was reading a book by Lenin or on Lenin. He continued his reading and said, 'Wait a while. A revolutionary is talking to another revolutionary.' There was something in his voice which made the executioners pause. Bhagat Singh continued to read. After a few moments, he flung the book towards ceiling and said, "Let us go."

How he escaped after killing of JP Saunders

Along with his comrade Sukhdev, Bhagat Singh shot dead JP Saunders in a case of mistaken identity on December 17, 1927. The freedom fighter was a Sikh by birth. Following the killing of Saunders he shaved his beard and cut his hair to avoid being recognised and arrested for the killing so that he could escape from Lahore to Calcutta. The duo had planned to kill superintendent of police James Scott to avenge the death of Lala Lajpat Rai, but the plan went awry and the 21-year-old British police officer was assassinated instead.

To escape, he needed the cover of a respectable married man to get out of the police dragnet. 'Fake' wife Durga Devi, better known as ‘Durga Bhabi, was the lady who bravely assisted Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev in their escape from Lahore in November 1928. Lalit Mohan, son of Virendra and son-in-law of Durga Das Khanna, both comrades of Bhagat Singh, recounted this incident. “At the time, the Punjab police’s focus was on nabbing the two revolutionaries and a massive manhunt was underway. As Lahore teemed with policemen, Durga Devi volunteered to 'act' as Bhagat Singh’s wife to help him escape. At the appointed time, Durga Devi along with Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev left for the Lahore railway station. Bhagat Singh was dressed as an Anglo-Indian in a suit and a felt hat. He carried Durga Devi’s infant son in his arms while Sukhdev posed as the domestic help.” 400 policemen were at the platform on the lookout for Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev that day, but they all played their parts brilliantly and managed to escape.

Heart of gold

And while Bhagat Singh did not marry himself, he made sure his friend Durga Das Khanna did not walk out from his own wedding. Lalit Mohan recalled the events of that day based on what his father-in-law told him . “In January 1927, Durga Das was persuaded by Rajguru and Sukhdev to slip away from his own wedding right before the ceremony with all the money collected from the shaguns during the milni. When Bhagat Singh learnt Durga Das had forsaken his family and bride-to-be. Bhagat Singh popped the question: ‘What will happen to your mother?’ Durga Das replied, ‘She will probably die of shame and embarrassment.’ At this point Sukhdev laughed: "Don’t worry. We will erect a memorial to her when India becomes free." This levity did not go down too well with Bhagat Singh who said: ‘No. We cannot let that happen. I think you better go back.’ Durga Das Khanna took his advice, and did, indeed, return home to a family in panic over the missing groom and got married that very night.”

'Inquilab Zindabad’

Bhagat Singh coined the phrase 'Inquilab Zindabad,’. A year after the mistaken killing, he and comrade Batukeshwar Dutt threw bombs in the Central Assembly Hall in Delhi on April 8, 1929, and shouted “Inquilab Zindabad!” He did not resist his arrest at this point, Eventually, ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ became the slogan of India's armed freedom struggle. The bombs Bhagat Singh and his associate threw in the Central Assembly in Delhi were made from low grade explosives. They were intentionally lobbed away from people in the corridors were meant only to startle and not harm. This was confirmed by the British investigation and the forensic report of the incident.

Last moments

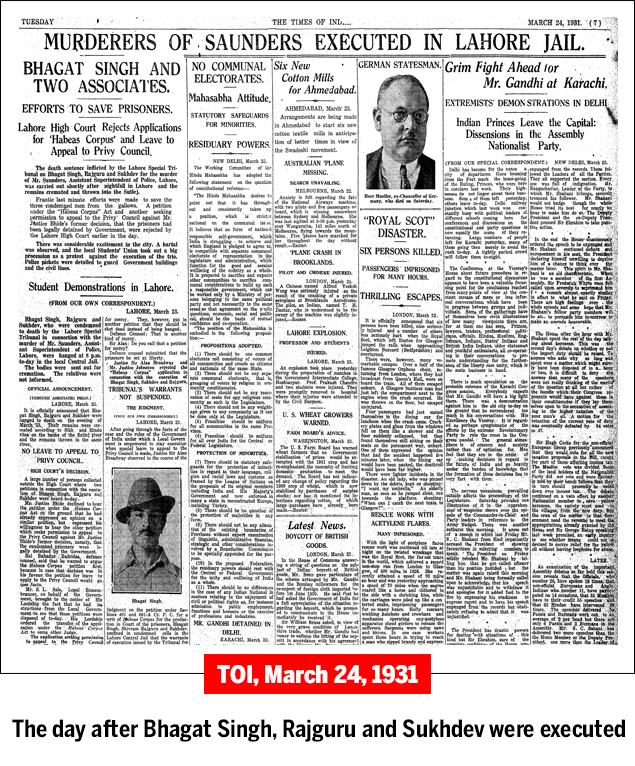

Bhagat Singh was sentenced to be hanged on March 24, 1931. His hanging was, however, brought forward by 11 hours to March 23, 1931 at 7:30 pm. Singh was thus hanged an hour ahead of the official time and was secretly cremated on the banks of the river Sutlej by jail authorities. According to reports, no magistrate was willing to supervise the hanging. After the original death warrants expired it was an honorary judge who signed and oversaw the hanging.

Recounting Bhagat Singh’s final moments, Virendra (Bhagat Singh’s comrade), who was lodged in the same jail as the three condemned prisoners, wrote in his memoirs - "There was a Muslim barber who would go on his daily round to the area where Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were lodged, and also visit us. He knew what was happening in the jail. The newspapers had reported that the execution had been fixed for March 24. According to the jail rules all hangings would take place at 7 am in the summer and at 8 am in the winter. On any such day all other prisoners were kept locked up in their cells until after the dead men's bodies had been removed from the prison premises.

"In the afternoon of the 23rd, the prison barber came running to us and said, 'Sardarji (Bhagat Singh) says that they will probably be hung today itself. He has wished the two of you (Virendra and Ehsan Elahi) Vande Mataram.’” The next morning, Virendra and the other prisoners asked the warder, who was present at the execution, how the three rebels had conducted themselves as they approached death, This is what Virendra wrote - "At first he would not speak. When he did tears welled up in his eyes. He said, 'Ever since I have joined Jail service I have seen dozens being hung. But I have never seen anyone embrace death with such courage and fortitude.' "He said that after Bhagat Singh had changed into the outfit prescribed for the condemned and was about to reach the gallows he pleaded with him, 'Son, I have a request. It is a matter of just a few minutes more. At least remember Wahe-guru now.' The warder told us that Bhagat Singh laughed at his words and said, 'Sardarji, I did not take His name all my life. In fact, when I saw how the poor and the oppressed were being treated I even rebuked Him. Now if I pray to Him, when death stares me in the face, He will say that this man is a hypocrite and a coward. So what effect will my prayer possibly have on him? If I don't change my opinion, at least He will concede that this man was honest.'"

With those words he ascended the platform.

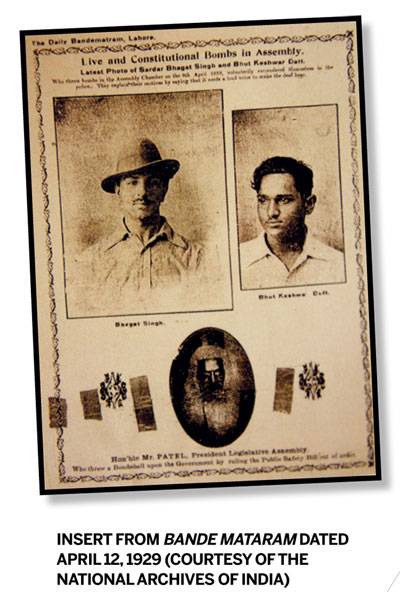

The iconic photo

An iconic photo of Bhagat Singh in a hat was deliberately circulated widely with the idea that people would be able to imagine the revolutionary not as a violent terrorist, but instead visualise stories, songs, poems and sayings praising his heroism. The portrait’s aim was to create a gentler image of the leader in the people’s memory, contradicting British charges that he was a ruthless killer, according to an excerpt from the book "A Revolutionary History of Interwar India: Violence, Image, War and Text".

The hat photograph was taken a few days prior to the action in the Legislative Assembly, in the studios of Ramnath Photographers at Kashmiri Gate in Delhi. Jaidev Kapoor, an HSRA member, arranged for the photograph to be taken. He specifically asked the photographer to make a memento of Bhagat Singh, specifying that “our friend is going away, so we want a really good photograph of him.”

His felt hat

Kama Maclean, That Bhagat Singh hat, March 30, 2016: The India Today

A new book traces perhaps the earliest image of political propaganda in India.

From: Kama Maclean, That Bhagat Singh hat, March 30, 2016: The India Today

Bhagat Singh's celebrity, over and above all other revolutionaries who gave their lives to the cause, has been a source of wonderment for some time. In the days after his execution, Jawaharlal Nehru wondered aloud how it was that "a mere chit of a boy suddenly leapt to fame". He did not attend the gallows alone; his friends Sukhdev and Rajguru were hanged alongside him. Yet even in the months before his hanging, the condemned trio was frequently referred to as 'Bhagat Singh and others'. How can we explain his prominence over that of his fellow martyrs, or over important members of the HSRA (Hindustan Socialist Republican Army), such as Chandrashekhar Azad? Bhagat Singh's hat portrait, and the extraordinary campaign around it, holds some of the answers.

The photograph is a fairly conventional studio portrait. The young revolutionary-he was 21 when he posed for the photograph-stares calmly into the camera, as if to defy the empire and the weighty charges about to be brought against him, namely, that he had "been engaged in conspiracy to wage war against his Majesty, the King Emperor, and to deprive him of the Sovereignty of British India...".

From: Kama Maclean, That Bhagat Singh hat, March 30, 2016: The India Today

Bhagat Singh knew these charges would lead to a death sentence, yet he stands cool and poised, a felt hat tipped on his head. The photograph has become an icon of defiant nationalism, widely referenced in poster art and calendars, (and) a regular feature of the contemporary urban landscape, readily encountered on cars and hoardings, in bazaars, on posters and books.

The ubiquity of the image is such that it is frequently compared to Alberto Korda's famous photograph of Che Guevara. Both were photogenic, capturing the romance, idealism and sacrifices demanded of the revolutionary. Both photographs, too, have been so widely appropriated that they have become disconnected from their historical context. In Bhagat Singh's case, this is partly because there is considerable uncertainty about the nature of its production. Some have assumed it was taken to be fixed to a security pass; others have speculated the police took it immediately after his arrest in 1929. Neither of these is correct.

Prelude to a martyrdom

Bhagat Singh's photo-portrait may appeal to different viewers for any number of reasons...his youthful handsomeness, his clear, steady stare, and his rather fashionable hat, set at an angle, just so. But thinking of the photograph in Barthesian terms, "that element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow and pierces me" is the knowledge that the dashing young man who meets our gaze will be hanged-and he knows it. The photograph becomes all the more compelling with the realisation that Bhagat Singh explicitly had it taken as a political tactic, before provoking the government of British India to seal his fate. The portrait, therefore, can be seen as both a prelude to and a vital ingredient in the widespread acceptance of him as a shaheed (martyr). This story is largely unknown and is one worth telling. Besides Bhagat Singh's direct eye contact, perhaps the most arresting feature of the portrait is his stylish but obviously western hat. Bhagat Singh had, in order to wear the said hat, renounced his kesh (the uncut hair of a Sikh) and turban when disguising himself became vital to evading capture, in September 1928. After the widespread distribution of the photograph, Bhagat Singh's hat would become his defining attribute. Only relatively recently have images of him wearing a turban become popular. It is important to note, however, that his Sikh heritage was explicitly acknowledged in the 1930s.

Memento in the making

The infamous hat photograph was taken a few days prior to the action in the Legislative Assembly, probably around April 4, in the studios of Ramnath Photographers at Kashmiri Gate in Delhi. Jaidev Kapoor, the HSRA member who did much of the reconnaissance and planning for the attack, arranged (it). He specifically asked the photographer to make a memento of Bhagat Singh, specifying "our friend is going away, so we want a really good photograph of him". B.K. Dutt was photographed on a separate occasion, but with the same instruction.

While the photographs were being developed, Bhagat Singh and Dutt were attending the Legislative Assembly on a daily basis, closely observing the debate on the Public Safety Bill; their plan was to throw the bombs at the exact moment the president of the House moved to give his ruling, which happened on the morning of April 8. A number of newspaper reporters were present in the Assembly at the time of the bombing, as were many political notables, both Indian and British, which no doubt added to the sense of excitement with which the so-called Assembly Outrage was initially carried in the press.

At Ramnath Photographers, however, production was delayed and Kapoor was unable to collect the photographs before the action. Ramnath was also contracted to take photographs for the police and had been summoned to the police station in Old Delhi, where Bhagat Singh was taken after his arrest. These police photographs have not yet surfaced, but were almost certainly used, as the police "ransacked all hotels in Delhi with photographs of the accused".

The enduring image

Martyrdom was very much on Bhagat Singh's mind; he had resolved that his struggle against British imperialism would conclude in his early death. Unwilling to leave behind a widow, he had refused to marry, and had secured a solemn promise from a close friend, Jaidev Gupta, to take care of family members in his absence. He had a lucid understanding of how martyrs were made, and his work as a journalist shows that he had a strong appreciation of the utility of photography in bringing texture to a story. In 1926, he had assisted in the compilation of a special issue on the death penalty, Chand ka Phansi Ank (Chand's Hanging Edition). Bhagat Singh had contributed entries on several revolutionaries, and he took care to see that their photographs accompanied the text. His acute awareness of the potency of martyrdom is clear in his writings. Shortly before his execution, fellow prisoners passed him a note, asking him if he preferred to live. His response was unambiguous: "My name has become a symbol of Indian revolution. ?If I mount the gallows with a smile, that will inspire Indian mothers and they will aspire that their children become Bhagat Singh. Thus the number of persons ready to sacrifice their lives will increase enormously. It will then become impossible for imperialism to face the tide of the revolution."

Ramnath Studio's portrait of Bhagat Singh played a major role in the above process. "It was Bhagat Singh's desire," Jaidev Kapoor recalled, "and mine also, that after the action the pictures would be published and distributed widely." Kapoor reproduced and arranged for them to be delivered to major Indian-owned newspapers. In Delhi, they were hand-delivered to the Hindustan Times office by Bimal Prasad Jain, a junior worker in the HSRA. He left the packet addressed to the editor, J.N. Sahni, with a chaprasi and disappeared. "When Mr Sahni opened the envelope, I heard him shouting to the peon: 'Go and bring that Sahib who has brought that envelope.' But I was nowhere to be seen."

Fear of being accused of sedition meant the photographs were not published immediately. Kapoor later "found out that all the presswallahs were waiting to see who would publish the photograph first". It was the Lahore-based Bande Mataram that obliged, publishing the photographs on April 12. The pictures appeared not in the actual pages of the newspaper, but on a loose, one-sided poster issued inside; although an Urdu newspaper, the poster was in English. The editor, Lala Feroze Chand, was questioned by police in May after a raid on his home turned up a portrait of Bhagat Singh. Chand conceded he had agreed to publish the photographs of Bhagat Singh and Dutt. Called as a prosecution witness, Chand eventually confessed he knew Sukhdev; he did not mention he was a friend of Bhagat Singh. Decades later, in an oral history testimony, Chand reflected, "That photograph became very popular throughout the country for that was the first glimpse people had of Bhagat Singh-this young Sikh chap with a felt hat on his head."

Maclean is author of A Revolutionary History of Interwar India: Violence, Image, Voice and Text (Penguin Books, Pages: 305; Price: Rs 599), excerpts of which are carried above.

A ‘revolutionary terrorist’?

‘Bhagat Singh called himself a terrorist’

The Times of India, May 02 2016

Akshaya Mukul

Bhagat Singh himself said he was terrorist: Habib

Eminent historian Irfan Habib has come to the defence of Bipan Chandra and other historians who together authored India's Struggle for Independence in 1988. The book which has been part of Delhi University's history curriculum and refers to fredom fighter Bhagat Singh as a “revolutionary terrorist“ has been at the centre of controversy recently .

Habib said, “I did not agree with many points in the book but calling Bhagat Singh revolutionary terrorist was not wrong.“ He said Hindustan Republican Socialist Association to which Bhagat Singh belonged had itself in its resolution of 1929 had used the word terrorist. “In fact, HRSA 's manifesto of 1929 distributed during the Lahore session of the Congress said `we are being criticised for our terrorist policies but we are resorting to terror in response to British terror',“ Habib said.

He also pointed to Bhagat Singh's rejoinder to Mahatma Gandhi's criticism of terror activity in which he had said that terrorism in itself is not revolution but no revolution is complete without terror.

Habib said that in later stage of his life, Bhagat Singh had admitted that he was terrorist for some time in the beginning. Terrorist and terror have become pejorative words now because innocent people are being killed by them, he pointed out.

A brand name

Bhagat Singh merchandise/ 2016

The Times of India, May 08 2016

Joeanna Rebello

The revolutionary is fast turning into an urban pop culture icon with his face on everything from bags and bric-a-brac to mugs and mobile covers. Capitalism Zindabad!

Bhagat Singh merchandise on line -a screen-printed T-shirt and a backpack are quite common. Now and then, the question remains that can we term him a "revolutionary terrorist"!

Stopping the sale and distribution of the Hindi edition of historian Bipan Chandra's book India's Struggle for Independence, capitulating to ABVP protests over the book's references to Bhagat Singh as a revolutionary terrorist.Whether or not the rest of the country's 18-35-year-olds approve of, or even know of the disputed description, the protagonist himself has their unequivocal vote.

For young hipsters, Singh is a desi daredevil, a rebel with a cause, a man of the hour.Literally . He gazes out from watches and wall clocks, but he's also on mugs, wallets, cushions, laptop skins, key-chains, lamps, mobile covers and even wall decals, bearing either of the two versions of his iconic image -turbaned or hatted. The more abstract art pictures him in fractals, or simply with the legend `Shaheed' or `Inquilab Zindabad' and a grim noose; some only feature a waxed moustache, shorthand like Gandhi's wire-rim glasses.

The universe of Bhagat Singh merchandise on e-commerce sites has exploded in the last year or two, generating new product forms every month. “I come from Punjab, where Bhagat Singh is very popular, so I thought people elsewhere would love him too. I believe his rebelliousness appeals to young people,“ says Puneet Gupta, co-founder of the merchandise e-store Poster Guy, which retails goods printed with graphic art sourced from designers across the country. Their `Bhagat Singh' range debuted around Independence Day last year.

Ideology, views

S Irfan Habib’s summation

March 20, 2019: The Times of India

‘Bhagat Singh was always a revolutionary nationalist… Indian cultural ethos was deeply ingrained in him’

Bhagat Singh is an uncommon figure from the pre-independence era in the sense that not only has he been appropriated by parties across the ideological spectrum, even Sikh extremists and some Pakistanis venerate him. Historian S Irfan Habib, in a conversation with Manimugdha S Sharma, unpacks the man and his beliefs.

In the Left vs Right struggle to appropriate Bhagat Singh, how would you place him?

It is very convenient and easy to appropriate him as a martyr and a nationalist, which the Right does all the time. However, they are not even remotely close to what Bhagat Singh stood for. He was never part of any institutionalised Left in his short life. Yet he held up a socialist vision for independent India. He would surely belong to one of the many shades of the Left. Many of his comrades who lived after independence joined the communist parties or the Congress. Hardly any of them moved to the Right.

What do we make of the popular image of Bhagat Singh as a gun-toting nationalist who earns his revolutionary credentials by killing British officials?

This was an image created through the British colonial records that always referred to him and others as blood-thirsty nationalists. Unfortunately that romantic image was appropriated by many of us with a lot of pride. In the process we lost track of his Marxist revolutionary passion to change the world. Going back to that image is difficult now, yet we should engage with the huge corpus of revolutionary literature he has left behind.

Bhagat Singh himself declared that he was a terrorist but later found it to be a futile course of action. Could you shed light on this?

This happens quite often. It is true that Bhagat Singh did call himself a terrorist while talking about his evolution as a revolutionary thinker. He clearly distanced himself from it and instead emphasised on the mass mobilisation of labour, peasants and the youth. Till mid-eighties, many senior historians called him revolutionary-terrorist but there was no outrage; even his brothers were around but none pointed that out. We became more sensitive since terrorism acquired a much uglier image globally.

For me, Bhagat Singh was always a revolutionary nationalist.

When Bhagat Singh invokes ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’, or universal brotherhood, and argues for ‘Vishvabandhuta’, or world friendship, do we see a bid to wed Indian cultural ethos with socialist internationalism?

Apart from being a serious socialist thinker, Indian cultural ethos was deeply ingrained in Bhagat Singh. He effortlessly complemented the two, which is evident in many of his writings. He did begin with Vishvabandhuta but could easily move to say that universal brotherhood is not tenable as long as words like black and white, civilised and uncivilised, ruler and ruled, rich and poor, touchable and untouchable exist.

What did Bhagat Singh think about Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose? How do we place him in the context of today’s Nehru-Bose binary?

Bhagat Singh expressed his views in a detailed article on both of them. He found Bose and Nehru to be the most popular young leaders who were making their presence felt. To quote him, “Both are wise and true patriots. Still there are considerable differences between the views of the two leaders”.

He found Bose a reformist and an emotional Bengali, while Nehru was for him a revolutionary who appealed to the young men and women to rebel and build a new society. Bhagat Singh urged the “Punjabi youths to follow him (Nehru), so that they may know the true meaning of Inquilab (revolution), the need for Inquilab in Hindustan, and the place of Inquilab in the world”.

Singh was disturbed by communalism and argued that communal politicians and sections of the press were responsible for it. Is that argument still valid?

Unfortunately, yes. Many of our politicians and political parties today indulge in blatantly communal and divisive politics, Bhagat Singh called such leaders as politically bankrupt. Bhagat Singh is glorified and most political parties shamelessly use his image to garner votes, but their stand is antithetical to his inclusive and cosmopolitan vision. Bhagat Singh wrote in 1928 that journalism, once a noble profession has now become evil. They stoke passions through sensational headlines and incite people against each other. He believed that “the actual duty of newspapers is to educate, to liberate people from narrow-mindedness, eradicate fundamentalism, to help in creating a sense of fraternity among people, and build a common nationalism in India”.

Is his message to students relevant?

Writing about the policies of the colonial government, Singh said, “Then it becomes a question of what the government likes or is annoyed by. Should students be taught the lesson of sycophancy from the moment they are born?” The relevance is obvious.

Refused to pray before he was hanged

March 23, 2021: The Times of India

On March 23, 1931, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged for the killing of British officer JP Saunders. They had intended to shoot superintendent of police James Scott, whose lathicharge during an anti-Simon Commission protest in Lahore had caused the death of Lala Lajpat Rai in November 1928. But as the killing was a symbolic act, they considered their mission successful despite the mix-up.

A few months later, Singh and BK Dutt threw a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly chamber before courting arrest. Singh’s daring acts and defiance of the British are well-known, but Gurgaon resident Lalit Mohan, son of Virendra and son-in-law of Durga Das Khanna, both associates of Bhagat Singh, says what people don’t see is his extraordinary humanity.

A Sensitive Man

Determined and audacious though he was, Singh had a softer side too, and Mohan might not have met his better half without it. “On a cold night in January 1927, Rajguru and Sukhdev persuaded my father-in-law Durga Das Khanna to slip away from his own wedding with all the shagun money, right before the ceremony, because they were in desperate need of funds. But when Singh heard he had forsaken his family and his bride-tobe, he turned pensive. ‘What will happen to your mother?’ he said. Durga Das replied, ‘She will probably die of shame and embarrassment.’ At this, Sukhdev laughed and said, ‘Don’t worry, we will erect a memorial to her when India becomes free.’”

Mohan said his father-inlaw told him that Singh did not like the joke. “No, we cannot let that happen. I think you had better go back,” Singh said to his friend, and Durga Das returned home and got married, much to the relief of his family.

Not a ‘Terrorist’

Singh shot Saunders, and on April 8, 1929, he also threw a bomb inside the assembly chamber, but he was no terrorist. “Where he and his fellow revolutionaries differ from the present-day mass killers is that they never terrorised innocent people. He did use the gun, but very selectively, always careful to avoid collateral damage,” Mohan said. In the Legislative Assembly incident, “many leading lights of the British government were seated before them. But he was not out to kill anyone. He did not try to escape. He sacrificed his life just to make a point.” Later, in his statement to the court, Singh himself said: “We hold human life sacred beyond words... Our sole purpose was ‘to make the deaf hear’ and to give the heedless a timely warning.”

Honesty, Above All

Mohan’s father Virendra “had a fascinating account of Singh’s final moments based on what chief prison warder Charat Singh, who was present at the execution, told him.” This interaction is described in Virendra’s memoirs, ‘Destination Freedom’: “As Singh was about to reach the gallows, he (Charat Singh) pleaded with him, ‘Son, it is a matter of just a few minutes more. At least remember Wahe-guru now.’ The warder told us that Bhagat Singh laughed at his words and said, ‘Sardarji, I did not take His name all my life. In fact, when I saw how the poor and the oppressed were being treated, I even rebuked Him. Now if I pray to Him, when death stares me in the face, He will say this man is a hypocrite and a coward. So, what effect will my prayer possibly have on Him? If I don’t change my opinion, at least He will concede this man was honest.’”

Last words

Devyani Mohan, March 23, 2021: The Times of India

From: Devyani Mohan, March 23, 2021: The Times of India

From: Devyani Mohan, March 23, 2021: The Times of India

From: Devyani Mohan, March 23, 2021: The Times of India

On March 23, 1931, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged for the killing of British officer JP Saunders. The man they actually wanted was superintendent of police, James Scott, who had rained lathi blows on one of India’s most respected leaders, Lala Lajpat Rai during an anti-Simon Commission protest, leading to his death on November 17, 1928. It was a symbolic action; the mistaken identity was of little relevance.

To escape the massive manhunt that was underway in Lahore, Bhagat Singh, a bachelor, realised he needed the cover of a respectable married man. He had already cut his hair short and changed his attire but he knew the disguise wasn't enough.

Gurgaon resident Lalit Mohan, son of Virendra and son-in-law of Durga Das Khanna, both associates of Bhagat Singh, recounted the escape. "My father told me that at the time, the Punjab police’s entire focus was on nabbing the revolutionaries. Bhagat Singh decided to enlist the help of Durga Devi, who was married to his friend and comrade Bhagwaticharan. She offered to ‘act' as his wife. On the appointed day, Bhagat Singh dressed as an Anglo-Indian in a well-cut suit and felt hat, and Durga Devi arrived at the railway station. He carried Durga Devi's infant son in his arms. Rajguru, dressed as the domestic help, accompanied them." he said.

"Around 400 policemen were present at the station that day, but Bhagat Singh and Durga Devi walked confidently into the first-class compartment, while Rajguru went inside third class. All three played their parts brilliantly and managed to escape to Calcutta," Mohan said.

Determined and audacious though he was, Bhagat Singh had a softer side too, and Mohan might not have met his better half without it. “On a cold winter night in January 1927, Rajguru and Sukhdev persuaded my father-in-law Durga Das Khanna to slip away from his own wedding with with all the shagun money collected right before the ceremony because they were in desperate need for funds. He was all ready to board the next train out of Lahore for an operation in Rawalpindi. When Bhagat Singh learnt Durga Das had forsaken his family and bride-to-be, his mood turned pensive: ‘What will happen to your mother?’ he asked. Durga Das replied, ‘She will probably die of shame and embarrassment.’ At this point Sukhdev laughed and said: 'Don’t worry. We will erect a memorial to her when India becomes free.'”

This levity, Mohan said, did not go down too well with Bhagat Singh, who said: 'No. We cannot let that happen. I think you better go back.' Durga Das took his friend's advice – he returned home and got married, much to the relief of a panic-stricken family.

The three who ‘executed’ Inspector Saunders were sentenced to be hanged on March 24, 1931. But the hanging was brought forward by 11 hours to March 23 at 7.00pm.

Mohan said his father Virendra was incarcerated in the same prison at the time, on a different charge. “He had a fascinating account of Bhagat Singh’s final moments based on what chief prison warder Charat Singh, who was present at the execution, told him,” he said. This interaction is described in Virendra’s memoirs, Destination Freedom, “We asked the warder how the three rebels had conducted themselves as they approached death. At first, he would not speak. When he did tears welled up in his eyes. He said, 'Ever since I have joined jail service, I have seen dozens being hanged. But I have never seen anyone embrace death with such courage and fortitude.'”

"He said that after Bhagat Singh had changed into the outfit prescribed for the condemned and was about to reach the gallows, he (the warder) pleaded with him, 'Son, I have a request. It is a matter of just a few minutes more. At least remember Wahe-guru now.' The warder told us that Bhagat Singh laughed at his words and said, 'Sardarji, I did not take His name all my life. In fact, when I saw how the poor and the oppressed were being treated, I even rebuked Him. Now if I pray to Him, when death stares me in the face, He will say that this man is a hypocrite and a coward. So, what effect will my prayer possibly have on him? If I don't change my opinion, at least He will concede that this man was honest,'" writes Virendra. With those words he ascended the platform.

Can such a man be called a terrorist? "Where he and his fellow activists differed from the present-day mass killers is that they never ‘terrorised’ innocent people. He did use the gun, but very selectively, always careful to avoid any collateral damage," Mohan said. He cited the incident on April 8, 1929, when Bhagat Singh and fellow revolutionary BK Dutt hurled a bomb in the Central Legislative Assembly chamber. "He came to Delhi from Calcutta knowing fully well that if arrested he was certain to be hanged because of his role in Saunders’ assassination. On benches in front of them, like sitting ducks, were many leading lights of the British government. Had he been a terrorist, he would have found the temptation to do them in irresistible. But he was not out to kill any person. He did not try to escape. He sacrificed his life just to make a point," Mohan said.

The point that Bhagat Singh also made in his statement to the court following the incident was this:. “We hold human life sacred beyond words.... We dropped the bomb to register our protest on behalf of those who had no other means left to give expression to their heartrending agony. Our sole purpose was to make ‘to make the deaf hear’ and to give the heedless a timely warning.”