Banjara

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

(This article is based principally on a Monograph on the Banjara Clan, by Mr. N. F. Cumberlege of the Berar Police, believed to have been first written in 1869 and reprinted in 1882 (Notes on the Banjaras written by Colonel Mackenzie and printed in the Berar Census Report (1881) and the Pioneer newspaper (communicated by Mrs. Horsburgh) ; Major Gunthorpe's C7-iminal Tribes ; papers by Mr. M. E. Khare, Extra-Assistant Commissioner, Clianda ; Mr. Narayan Rao, Tahr. Betul ; Mr. Mukund Rao, Manager, Pachmarhi Estate ; and information on the caste collected in Yeotnial and Nimar.)

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Banjara, Wanjari, Labhana, Mukeri

A carriers and drivers of pack- bullocks

The caste of carriers and drivers of pack- bullocks. In 1911 the Banjaras numbered about 56,000 persons in the Central Provinces and 80,000 in Berar, the caste being in greater strength here than in any part of India except Hyderabad, where their total is 174,000. Bombay comes next with a figure approaching that of the Central Provinces and Berar, and the caste belongs therefore rather to the Deccan than to northern India. The name has been variously explained, but the most probable derivation is from the Sanskrit

banijya kanr, a merchant. Sir H. M. Elliot held that the name Banjira was of great antiquity, quoting a passage from the Dasa Kumara Charita of the eleventh or twelfth century. But it was subsequently shown by Professor Cowcll that the name l^anjara did not occur in the original text of this work.^ Banjaras are supposed to be the people mentioned by Arrian in the fourth century B.C., as leading a wandering life, dwelling in tents and letting out for hire their beasts of burden.' But this passage merely proves the existence of carriers and not of the Banjara caste. Mr. Crooke states '^ that the first mention of Banjaras in Muhammadan his- tory is in Sikandar's attack on Dholpur in A.D, 1504. It seems improbable, therefore, that the Banjaras accompanied the different Muhammadan invaders of India, as might have been inferred from the fact that they came into the Deccan in the train of the forces of Aurangzeb.

Two Muhammadan sections

The caste has indeed two Muhammadan sections, the Turkia and Mukeri.^ But both of these have the same Rajput clan names as the Hindu branch of the caste, and it seems possible that they may have embraced Islam under the proselytising influence of Aurangzeb, or simply owing to their having been employed with the Muhammadan troops. The great bulk of the caste in southern India are Hindus, and there seems no reason for assuming that its origin was Muhammadan.

Charans identified with Banjaras

It may be suggested that the Banjaras are derived from the Charan or Bhat caste of Rajputana. Mr. Cumberlege, whose Monograph on the caste in Berar is one of the best from the authorities, states that of the four divisions existing there the Charans are the most numerous and by far the most interesting class.*"

2. Ban- o^^Bhats

(' Mr. Crooke's Tribes a)id Castes, actions Bombay Literary Society, \o\.\. art. Banjara, para. i. 183) says that "as carriers of grain 2 Berar Census Report (1881), for Muhammadan armies the Banjaras p. 150. have figured in history from the days 2 Ibidem, para. 2, quoting Dowson's of Muhammad Tughlak (a.D. 1340) to Elliot, V. 100. those of Aurangzeb. * Khan Bahadur Fazalullah Lut- ^ Sir H. M. Elliot's Sttpplemeiital fullah Farldi in the Bombay Gazetteer Glossary. (Muhammadans of Gujarat, p. 86) ® Monograph on ike Batijdra Clan, quoting from General Briggs [Trans- p. 8,)

Customs

In the article on Bhat it has been explained how the Charans or bards, owing to their readiness to kill themselves rather than give up the property entrusted to their care, became the best safe-conduct for the passage of goods in Rajputana. The name Charan is generally held to mean ' Wanderer,' and in their capacity of bards the Charans were accustomed to travel from court to court of the different chiefs in quest of patronage.

They were first protected by their sacred character and afterwards by their custom of trdga [traga?] or chdndi [chandi??], that is, of killing themselves when attacked and threatening their assailants with the dreaded fate of being haunted by their ghosts. Mr. Bhimbhai Kirparam ^ remarks : " After Parasurama's dispersion of the Kshatris the Charans accompanied them in their southward flight. In those troubled times the Charans took charge of the supplies of the Kshatri forces and so fell to their present position of cattle-breeders and grain-carriers. . . ." Most of the Charans are graziers, cattle-sellers and pack- carriers.

Colonel Tod says : ^ " The Charans and Bhats or bards and genealogists are the chief carriers of these regions (Marwar) ; their sacred character overawes the lawless Rajput chief, and even the savage Koli and Bhil and the plundering Sahrai of the desert dread the anathema of these singular races, who conduct the caravans through the wildest and most desolate regions.

In another passage Colonel Tod identifies the Charans and Banjaras ^ as follows : " Murlah is an excellent township inhabited by a community of Charans of the tribe Cucholia (Kacheli), who are Bunjarris (carriers) by profession, though poets by birth. The alliance is a curious one, and would appear incongruous were not gain the object generally in both cases. It was the sanctity of their office which converted our bardais (bards) into buujdrris [???], for their persons being sacred, the immunity ex- tended likewise to their goods and saved them from all imposts ; so that in process of time they became the free- traders of Rajputana. I was highly gratified with the reception I received from the community, which collectively advanced to meet me at some distance from the town. The procession was headed by the village elders and all the fair Charanis, who, as they approached, gracefully waved their scarfs over me until I was fairly made captive by the muses of Murlah ! It was a novel and interesting scene. The manly persons of the Charans, clad in the flowing white robe witii the high loose-folded turban inclined on one side, from which the Didla or chaplet was gracefully suspended; and the uaiqucs [??? or leaders, with their massive necklaces of gold, with the image of the pitriszvar {iiianes) depending therefrom, gave the whole an air of opulence and dignity.

(' Hindus of Gujarat, p. 214 e( seq. ^ Rajasthdn, i. 602. 3 Ibidem, ii. 570, 573.)

The females were uniformly attired in a skirt of dark-brown camlet, having a bodice of light-coloured stuff, with gold orna- ments worked into their fine black hair ; and all had the favourite chilris or rings of lidthiddnt (elephant's tooth) covering the arm from the wrist to the elbow, and even above it." A little later, referring to the same Charan community.

Caravan

Colonel Tod writes : " The id?tda or caravan, consisting of four thousand bullocks, has been kept up amidst all the evils which have beset this land through Mughal and Maratha tyranny.

The utility of these caravans as general carriers to conflicting armies and as regular tax- paying subjects has proved their safeguard, and they were too strong to be pillaged by any petty marauder, as any one who has seen a Banjari encampment will be convinced. They encamp in a square, and their grain-bags piled over each other breast-high, with interstices left for their match- locks, make no contemptible fortification. Even the ruthless Turk, Jamshid Khan, set up a protecting tablet in favour of the Charans of Murlah, recording their exemp- tion from dlnd contributions, and that there should be no increase in duties, with threats to all who should injure the community. As usual, the sun and moon are appealed to as witnesses of good faith, and sculptured on the stone. Even the forest Bhil and mountain Mair have set up their signs of immunity and protection to the chosen of Hinglaz (tutelary deity) ; and the figures of a cow and its kairi (calf) carved in rude relief speak the agreement that they should not be slain or stolen within the limits of Murlah."

In the above passage the community described by Colonel Tod were Charans, but he identified them with Banjaras, using the name alternatively. He mentions their large herds of pack-bullocks, for the management of which the Charans, who were graziers as well as bards, would naturally be adapted ; the name given to the camp, tdnda, is that generally used by the Banjaras ; the women wore ivory bangles, which the Banjara women wear.^ In com- menting on the way in which the women threw their scarves over him, making him a prisoner. Colonel Tod remarks : " This community had enjoyed for five hundred years the privilege of making prisoner any Rana of Mewar who may pass through Murlah, and keeping him in bondage until he gives them a got or entertainment. The patriarch (of the village) told me that I was in jeopardy as the Rana's repre- sentative, but not knowing how I might have relished the joke had it been carried to its conclusion, they let me escape.

" Mr. Ball notes a similar custom of the Banjara women far away in the Bastar State of the Central Provinces : " " To- day I passed through another Banjara hamlet, from whence the women and girls all hurried out in pursuit, and a brazen- faced powerful-looking lass seized the bridle of my horse as he was being led by the sais in the rear. The sais and chaprdsi [chaprasi?] were both Muhammadans, and the forward conduct of these females perplexed them not a little, and the former was fast losing his temper at being thus assaulted by a woman."

' This custom does not necessarily frequently wear the hair long, down to indicate a special connection between the neck, which is another custom of the Banjaras and Charans, as it is Kajputana. common to several castes in Kajputana ; ^ Jungle Life in India, p. 517. but it indicates that the Banjaras came Berar Census Report (1881), p. from Kajputana. Banjara men also 152.

Origins: The ancestors of the Banjaras

Colonel Mackenzie in his account of the Banjara caste remarks : ^ "It is certain that the Charans, whoever they were, first rose to the demand which the great armies of northern India, contending in exhausted countries far from their basis of supply, created, viz. the want of a fearless and reliable transport service. . . . The start which the Charans then acquired they retain among Banjaras to this day, though in very much diminished splendour and position.

As they themselves relate, they were originally five brethren, Rathor, Turi, Panwar, Chauhan and Jadon. But fortune particularly smiled on Bhika Rathor, as his four sons, Mersi, Multasi, Dheda and Khamdar, great names among the Charans, rose immediately to eminence as commissariat transporters in the north. And not only under the Delhi Emperors, but under the Satara, subsequently the Poona Raj, and the Subahship of the Nizam, did several of their descendants rise to consideration and power." It thus seems a reasonable hy[)othesis that the nucleus of the Banjara caste was constituted by the Charans or bards of Rajputana. Mr. Bhimbhai Kirparam ^ also identifies the Charans and Banjaras, but I have not been able to find the exact passage. The following' notice '"' by Colonel Tone is of interest in this connection [From ' Bombay Gazetteer, Hindus of Gujarat. - Letter on the Marathas (1798), p. 67, India Office Tracts.] : " The vast consumption that attends a Maratha army necessarily superinduces the idea of great supplies

yet, notwithstanding this, the native powers never concern them- selves about providing for their forces, and have no idea of a grain and victualling department, which forms so great an object in a European campaign. The Banias or grain-sellers in an Indian army have always their servants ahead of the troops on the line of march, to purchase in the circumjacent country whatever necessaries are to be disposed of. Articles of consumption are never wanting in a native camp, though they are generally twenty-five per cent dearer than in the town bazars ; but independent of this mode of supply the Vanjaris or itinerant grain- merchants furnish large quantities, which they bring on bullocks from an immense distance.

These are a very peculiar race, and appear a marked and discriminated people from any other I have seen in this country. Formerly they were considered so sacred that they passed in safety in the midst of contending armies ; of late, how- ever, this reverence for their character is much abated and they have been frequently plundered, particularly by Tipu." The reference to the sacred character attaching to the Banjaras a century ago appears to be strong evidence in favour of their derivation from the Charans. For it could scarcely have been obtained by any body of com- missariat agents coming into India with the Muhammadans. The fact that the example of disregarding it was first set by a Muhammadan prince points to the same conclusion. Mr. Irvine notices the Banjaras with the Mughal armies in similar terms : ^ "It is by these people that the Indian armies in the field are fed, and they are never injured by either army. The grain is taken from them, but invariably paid for. They encamp for safety every evening in a regular square formed of the bags of grain of which they construct a breastwork. They and their families are in the centre, and the oxen are made fast outside. Guards with matchlocks and spears are placed at the corners, and their dogs do duty as advanced posts. I have seen them with droves of 5000 bullocks. They do not move above two miles an hour, as their cattle are allowed to graze as they proceed on the march.

" One may suppose that the Charans having acted as carriers for the Rajput chiefs and courts, both in time of peace and in their continuous intestinal feuds, were pressed into service when the Mughal armies entered Rajputana and passed through it to Gujarat and the Deccan. In adopting the profession of transport agents for the imperial troops they may have been amalgamated into a fresh caste with other Hindus and Muhammadans doing the same work, just as the camp language formed by the superposition of a Persian vocabulary on to a grammatical basis of Hindi became Urdu or Hindustani. The readiness of the Charans to commit suicide rather than give up property committed to their charge was not, however, copied by the Banjaras, and so far as I am aware there is no record of men of this caste taking their own lives, though they had little scruple with those of others. The Charan Banjaras, Mr. Cumberlege states," first came to the Deccan with Asaf Khan in the campaign which closed with the annexation by the Emperor Shah Jahan of Ahmadnagar and Berar about 1630. Their leaders or Naiks were Bhangi and Jhangi of the Rathor and Bhagvvun Das of the Jadtin clan. Bhangi and Jhangi had 180,000 pack-bullocks, and Bhagwan Das 52,000.

[' Army of the Indian A/itt^hals, p. 192. '^ Monograph, p. 14, and Jierar Census Report (1S81) (Kilts), p. 151.]

[^ Rathor: These are held to have been de- scendants of the Bhika Rathor referred to by Colonel Mackenzie above. II C//ARAN n.lA'J.lh'AS U'l'I'If MlUJllAI. ARMJI'.S 169]

It was naturally an object with Asaf Khan to keep his commissariat well up with his force, and as Bhangi and Jhangi made difficulties about the supply of grass and water to their cattle, he gave them an order engraved on copper in letters of gold to the following effect :

Ranjan kd [ka?] pdtii [patu?] ChJiappar kd ghds [ka ghas?] Din kc tin k/ifin miidf; Aur jalidn AsafJdli ke ghorc IVahdn Blian^^i J/uDigi ko bail, which may be rendered as follows : "If you can find no water elsewhere you may even take it from the pots of my followers ; grass you may take from the roofs of their huts ; and I will pardon you up to three murders a day, provided that wherever I find my cavalry, Bhangi and Jhangi's bullocks shall be with them." This grant is still in the possession of Bhangi Naik's descendant who lives at Musi, near HingoH. He is recognised by the Hyderabad Court as the head Naik of the Banjara caste, and on his death his successor receives a khillat or dress-of-honour from His Highness the Nizam.

After Asaf Khan's campaign and settlement in the Deccan, a quarrel broke out between the Rathor clan, headed by Bhangi and Jhangi, and the Jadons under Bhagwan Das, owing to the fact that Asaf Khan had refused to give Bhagwan Das a grant like that quoted above. Both Bhangi and Bhagwan Das were slain in the feud and the Jadons captured the standard, consisting of eight thdns (lengths) of cloth, which was annually presented by the Nizam to Bhangi's descendants. When Mr. Cumberlege wrote (1869), this standard was in the possession of Hatti Naik, a descendant of Bhagwan D3.S, who had an estate near Muchli Bunder, in the Madras Presidency. Colonel Mackenzie states ^ that the leaders of the Rathor clan became so distinguished not only in their particular line but as men of war that the Emperors recognised their carrying distinctive standards, which were known as dJial 1 See note 3, p. 16S.

by the Rathors themselves. Jhangi's family was also represented in the person of Ramu Naik, the patel or headman of the village of Yaoli in the Yeotmal District. In 1791—92 the Banjaras were employed to supply grain to the British army under the Marquis of Cornwallis during the siege of Seringapatam/ and the Duke of Wellington in his Indian campaigns regularly engaged them as part of the commissariat staff of his army. On one occasion he said of them : " The Banjaras I look upon in the light of servants of the public, of whose grain I have a right to regulate the sale, always taking care that they have a proportionate advantage." - Mr. Cumberlege gives four main divisions of the caste in Berar, the Charans, Mathurias, Labhanas and Dharis. Of these the Charans are by far the most numerous and important, and included all the famous leaders of the caste mentioned above. The Charans are divided into the five clans, Rathor, Panwar, Chauhan, Puri and Jadon or Burthia, all of these being the names of leading Rajput clans ; and as the Charan bards themselves were probably Rajputs, the Banjaras, who are descended from them, may claim the same lineage. Each clan or sept is divided into a number of subsepts ; thus among the Rathors the principal subsept is the Bhurkia, called after the Bhika Rathor already mentioned ; and this is again split into four groups, Mersi, Multasi, Dheda and Khamdar, named after his four sons.

As a rule, members of the same clan, Panwar, Rathor and so on, may not intermarry, but Mr. Cumberlege states that a man belonging to the Banod or Bhurkia subsepts of the Rathors must not take a wife from his own subsept, but may marry any other Rathor girl. It seems probable that the same rule may hold with the other subsepts, as it is most unlikely that inter- marriage should still be prohibited among so large a body as the Rathor Charans have now become. It may be supposed therefore that the division into subsepts took place when it became too inconvenient to prohibit marriage ' General Briggs quoted by Mr. - A. Wellesley (1800), quoted in Farldi in Bombay Gazetteer, Muham- Mr. Crooke's edition of Hobson-Jobson, madans of Gujarat, p. 86. art. Brinjarry.

throughout the whole body of the sept, as has happened in other cases. The Mathuria Banjaras take their name from Mathura or M ultra and appear to be Brahmans. " They wear the sacred thread/ know the Gayatri Mantra, and to the present day abstain from meat and Hquor, subsisting entirely on grain and vegetables. They always had a sufficiency of Charans and servants {Jdiigar) in their villages to perform all necessary manual labour, and would not themselves work for a remuneration otherwise than by carrying grain, which was and still is their legitimate occupation ; but it was not considered undignified to cut wood and grass for the household. Both Mathuria and Labhana men are fairer than the Charans ; they wear better jewellery and their loin-cloths have a silk border, while those of the Charans are of rough, common cloth." The Mathurias are sometimes known as Ahiwasi, and may be connected with the Ahiwasis of the Hindustani Districts, who also drive pack-bullocks and call themselves Brahmans. But it is naturally a sin for a Brahman to load the sacred ox, and any one who does so is held to have derogated from the priestly order. The Mathurias are divided according to Mr. Cumberlege into four groups called Pande, Dube, Tiwari and Chaube, all of which are common titles of Hindustani Brahmans and signify a man learned in one, two, three and four Vedas respectively. It is probable that these groups are cxogamous, marrying with each other, but this is not stated. The third division, the Labhanas, may derive their name from lavana, salt, and probably devoted themselves more especially to the carriage of this staple. They are said to be Rajputs, and to be descended from Mota and Mela, the cowherds of Krishna.

The fourth subdivision are the Dharis or bards of the caste, who rank below the others. According to their own story "" their ancestor was a member of the Bhat caste, who became a disciple of Nanak, the Sikh apostle, and with him attended a feast given by the Mughal Emperor Humayun. Here he ate the flesh of a cow or buffalo, and in consequence became a Muhammadan and was circumcised. He was employed as a musician at the Mughal court, and his sons ^ Cumberlege, loc. cit. - Cumberlege, pp. 28, 29. 1/2 DANJARA PART joined the Charans and became the bards of the Banjara caste. " The Dharis," Mr. Cumberlege continues, " are both musicians and mendicants ; they sing in praise of their own and the Charan ancestors and of the old kings of Delhi ; while at certain seasons of the year they visit Charan hamlets, when each family gives them a young bullock or a few rupees. They are Muhammadans, but worship Sarasvati and at their marriages offer up a he-goat to Gaji and Gandha, the two sons of the original Bhat, who became a IMuhammadan. At burials a Fakir is called to read the prayers." Besides the above four main divisions, there are a num- ber of others, the caste being now of a very mixed character. Two principal Muhammadan groups are given by Sir H.

Elliot, the Turkia and Mukeri. The Turkia have thirty- six septs, some with Rajput names and others territorial or titular. They seem to be a mixed group of Hindus who may have embraced Islam as the religion of their employers. The Mukeri Banjaras assert that they derive their name from Mecca (Makka), which one of their Naiks, who had his camp in the vicinity, assisted Father Abraham in building.^ Mr. Crooke thinks that the name may be a corruption of Makkeri and mean a seller of maize. Mr. Cumberlege says of them : " Multanis and Mukeris have been called Banjaras also, but have nothing in common with the caste ; the Multanis are carriers of grain and the Mukeris of wood and timber, and hence the confusion may have arisen between them." But they are now held to be Banjaras by common usage ; in Saugor the Mukeris also deal in cattle.

From Chanda a different set of subcastes is reported called Bhusarjin, Ladjin, Saojin and Kanhejin ; the first may take their name from bliusa, the chaff of wheat, while Lad is the term -used for people coming from Gujarat, and Sao means a banker. In Sambalpur again a class of Thuria Banjaras is found, divided into the Bandesia, Atharadesia, Navadcsia and Chhadesia, or the men of the 52 districts, the 18 districts, the 9 districts and the 6 districts respectively. The first and last two of these take food and marry with each other. Other groups are the Guar Banjaras, apparently from Guara or Gwrda, a milkman, the ' Elliot's Races, quoted by Mr. Crooke, ibidem.

Guguria Baiijaras, wiio may, Mr. Ilira Lai suggests, take their name from trading in gi'tgar^ a Icind of gum, and the Bahrup l^anjaras, who arc Nats or acrobats. In Bcrar also a number of the caste have become respectable cultivators and now call themselves Wanjari, disclaiming any connection with the Banjaras, probably on account of the bad reputation for crime attached to these latter. Many of the Wanjaris have been allowed to rank with the Kunbi caste, and call themselves Wanjari Kunbis in order the better to dissociate themselves from their parent caste.

The existing caste is therefore of a very mixed nature, and the original Brahman and Charan strains, though still perfectly recognisable, cannot have main- tained their purity. At a betrothal in Nimar the bridegroom and his friends 6. Mar- come and stay in the next village to that of the bride. The two betrothal parties meet on the boundary of the village, and here the bride- price is fixed, which is often a very large sum, ranging from Rs. 200 to Rs. 1000. Until the price is paid the father will not let the bridegroom into his house. In Yeotmal, when a betrothal is to be made, the parties go to a liquor-shop and there a betel-leaf and a large handful of sugar are distributed to everybody. Here the price to be paid for the bride amounts to Rs. 40 and four young bullocks.

Prior to the wedding the bridegroom goes and stays for a month or so in the house of the bride's father, and during this time he must provide a supply of liquor daily for the bride's male relatives. The period was formerly longer, but now extends to a month at the most. While he resides at the bride's house the bridegroom wears a cloth over his head so that his face cannot be seen. Probably the prohibition against seeing him applies to the bride only, as the rule in Berar is that between the betrothal and marriage of a Charan girl she may not eat or drink in the bridegroom's house, or show her face to him or any of his relatives. Mathuria girls must be wedded before they are seven years old, but the Charans permit them to remain single until after adolescence.

Banjara marriages are frequently held in the rains, a 7. Mar- season forbidden to other Hindus, but naturally the most con- "^^^• venient to them, because in the dry weather they are usuall}'

travelling. For the marriage ceremony they pitch a tent in lieu of the marriage-shed, and on the ground they place two rice- pounding pestles, round which the bride and bridegroom make the seven turns. Others substitute for the pestles a pack - saddle with two bags of grain in order to sym- bolise their camp life. During the turns the girl's hand is held by the Joshi or village priest, or some other Brahman, in case she should fall ; such an occurrence being probably a very unlucky omen. Afterwards, the girl runs away and the Brahman has to pursue and catch her.

In Bhandara the girl is clad only in a light skirt and breast-cloth, and her body is rubbed all over with oil in order to make his task more difficult. During this time the bride's party pelt the Brah- man with rice, turmeric and areca-nuts, and sometimes even with stones ; and if he is forced to cry with the pain, it is considered luck}^ But if he finally catches the girl, he is conducted to a dais and sits there holding a brass plate in front of him, into which the bridegroom's party drop presents. A case is mentioned of a Brahman having obtained Rs. 70 in this manner. Among the Mathuria Banjaras of Berar the ceremony resembles the usual Hindu type.^ Before the wedding the families bring the branches of eight or ten different kinds of trees, and perform the Jiom or fire sacrifice with them.

A Brahman knots the clothes of the couple together, and they walk round the fire. When the bride arrives at the bridegroom's hamlet after the wedding, two small brass vessels are given to her ; she fetches water in these and returns them to the women of the boy's family, who mix this with other water previously drawn, and the girl, who up to this period was considered of no caste at all, becomes a Mathuria." Food is cooked with this water, and the bride and bridegroom are formally received into the husband's kttri or hamlet.

It is possible that the mixing of the water may be a survival of the blood covenant, whereby a girl was received into her husband's clan on her marriage by her blood being mixed with that of her husband.'^ Or it may be simply symbolical of the union of the families. In some localities after the wedding the bride and bridegroom are made to 1 Cumberlege, pp. 4, 5. ' Cumberlege, I.e. ^ This custom is noticed in the article on Khairwar. remar- riajre. II 111RTJ{ AND Dl'lA I'll 175 stand on two bullocks, which arc driven forward, and it is believed that whichever of them falls off first will be the first to die. Owing to the scarcity of women in the caste a widow 8. Widow is seldom allowed to go out of the family, and when her husband dies she is taken either by his elder or younger brother ; this is in opposition to the usual Hindu practice, which forbids the marriage of a woman to her deceased husband's elder brother, on the ground that as successor to the headship of the joint family he stands to her, at least potentially, in the light of a father. If the widow prefers another man and runs away to him, the first husband's relatives claim compensation, and threaten, in the event of its being refused, to abduct a girl from this man's family in exchange for the widow.

But no case of abduction has occurred in recent years. In Berar the compensation claimed in the case of a woman marrying out of the family amounts to Rs. 75, with Rs. 5 for the Naik or headman of the family. Should the widow elope without her brother- in-law's consent, he chooses ten or twelve of his friends to go and sit dharna (starving themselves) before the hut of the man who has taken her. He is then bound to supply these men with food and liquor until he has paid the customary sum, when he may marry the widow.^ In the event of the second husband being too poor to pay monetary compensation, he gives a goat, which is cut into eighteen pieces and distributed to the community.^

After the birth of a child the mother is unclean for five 9- Birth days, and lives apart in a separate hut, which is run up for ^"^ ^^^^'^^' her use in the kuri or hamlet. On the sixth day she washes the feet of all the children in the kuri, feeds them and then returns to her husband's hut. When a child is born in a moving tdnda or camp, the same rule is observed, and for five days the mother walks alone after the camp during the daily march. The caste bury the bodies of unmarried

1 Cuniberlege, p. 18. seems, however, to be a euphemism, 2 Mr. Hlra Lai suggests that this eighteen castes being a term of inde- custom may have something to do with finite multitude for any or no caste, the phrase Athara jat ke gayi, or The number eighteen may be selected 'She has gone to the eighteen castes,' from the same unknown association used of a woman who has been persons and those dying of smallpox and burn the others.

Their rites of mourning are not strict, and are observed only for three days. The Banjaras have a saying : " Death in a foreign land is to be preferred, where there are no kinsfolk to mourn, and the corpse is a feast for birds and animals " ; but this may perhaps be taken rather as an ex- pression of philosophic resignation to the fate which must be in store for many of them, than a real preference, as with most people the desire to die at home almost amounts to an instinct. 10. Reii- One of the tutelary deities of the Banjaras is Banjari 1'°"; . Devi, whose shrine is usually located in the forest. It is Devi. often represented by a heap of stones, a large stone smeared with vermilion being placed on the top of the heap to repre- sent the goddess. When a Banjara passes the place he casts a stone upon the heap as a prayer to the goddess to protect him from the dangers of the forest.

A similar practice of offering bells from the necks of cattle is recorded by Mr. Thurston : ^ "It is related by Moor that he passed a tree on which were hanging several hundred bells. This was a superstitious sacrifice of the Banjaras (Lambaris), who, passing this tree, are in the habit of hanging a bell or bells upon it, which they take from the necks of their sick cattle, expecting to leave behind them the complaint also. Our servants particularly cautioned us against touching these diabolical bells, but as a few of them were taken for our own cattle, several accidents which happened were imputed to the anger of the deity to whom these offerings were made ; who, they say, inflicts the same disorder on the unhappy bullock who carries a bell from the tree, as that from which he relieved the donor." In their houses the Banjari Devi is represented by a pack-saddle set on high in the room, and this is worshipped before the caravans set out on their annual tours. 11. Mithu Another deity is Mlthu Bhukia, an old freebooter, who lived in the Central Provinces ; he is venerated by the dacoits as the most clever dacoit known in the annals of the caste, and a hut was usually set apart for him in each 1 Ethnographic Notes in Southern India, p. 344, quoting from Moor's Narrative of Little s Detachment. Bhukia.

hamlet, a staff carrying a white flag being planted before it. Before setting out for a clacoity, the men engaged would assemble at the hut of Mlthu Bhtikia, and, burning a lamp before him, ask for an omen ; if the wick of the lamp drooped the omen was propitious, and the men present then set out at once on the raid without returning home. They might not speak to each other nor answer if challenged ; for if any one spoke the charm would be broken and the protection of Mithu 15hukia removed ; and they should either return to take the omens again or give up that particular dacoity altogether.^ It has been recorded as a characteristic trait of Banjaras that they will, as a rule, not answer if spoken to when engaged on a robbery, and the custom probably arises from this observance ; but the worship of Mlthu Bhukia is now frequently neglected.

After a successful dacoity a portion of the spoil would be set apart for Mlthu Bhukia, and of the balance the Nfiik or headman of the village received two shares if he participated in the crime ; the man who struck the first blow or did most towards the common object also received two shares, and all the rest one share. With Mlthu Bhukia's share a feast was given at which thanks were returned to him for the success of the enterprise, a burnt offering of incense being made in his tent and a libation of liquor poured over the flagstaff. A portion of the food was sent to the women and children, and the men sat down to the feast. Women were not allowed to share in the worship of Mlthu Bhukia nor to enter his hut.

Another favourite deity is Siva Bhaia, whose story is 12. Siva given by Colonel Mackenzie ^ as follows : " The love borne ^'^^'^• by Mari Mata, the goddess of cholera, for the handsome Siva Rathor, is an event of our own times (1874) ; she proposed to him, but his heart being pre-engaged he rejected her ; and in consequence his earthly bride was smitten sick and died, and the hand of the goddess fell heavily on Siva

himself, thwarting all his schemes and blighting his fortunes and possessions, until at last he gave himself up to her. She then possessed him and caused him to prosper exceedingly, gifting him with supernatural power until his fame was

^ Cumberlege, p. 35. 2 Bei-ai- Census Report, i8Si. VOL. II N

noised abroad, and he was venerated as the saintly Siva Bhaia or great brother to all women, being himself unable to marry. But in his old age the goddess capriciously wished him to marry and have issue, but he refused and was slain and buried at Pohur in Berar. A temple was erected over him and his kinsmen became priests of it, and hither large numbers are attracted by the supposed efficacy of vows made to Siva, the most sacred of all oaths being that taken in his name." If a Banjara swears by Siva Bhaia, placing his right hand on the bare head of his son and heir, and grasping a cow's tail in his left, he will fear to jaerjure himself, lest by doing so he should bring injury on his son and a murrain on his cattle.^

Naturally also the Banjaras worshipped their pack- cattle.'"' " When sickness occurs they lead the sick man to the feet of the bullock called Hatadiya.^ On this animal

no burden is ever laid, but he is decorated with streamers of red-dyed silk, and tinkling bells with many brass chains

and rings on neck and feet, and silken tassels hanging in all directions ; he moves steadily at the head of the convoy, and at the place where he lies down when he is tired they pitch their camp for the day ; at his feet they make their vows when difficulties overtake them, and in illness, whether

of themselves or their cattle, they trust to his worship for

a cure."

Mr. Balfour also mentions in his paper that the Banjaras call themselves Sikhs, and it is noticeable that the Charan subcaste say that their ancestors were three Rajput boys who followed Guru Nanak, the prophet of the Sikhs. The influ- ence of Nanak appears to have been widely extended over northern India, and to have been felt by large bodies of the people other than those who actually embraced the Sikh religion. Cumberlege states * that before starting to his marriage the bridegroom ties a rupee in his turban in honour of Guru Nanak, which is afterwards expended in sweetmeats.

' Cumberlege, p. 21. 2 The followini; instance is taken from Mr. I'alfour's article, ' Migratory Tribes of Central India,' inJ.A.S.B., new series, vol. xiii., quoted in Mr. Crook e's Tribes and Castes. ^ From the Sanskrit Hatya-adhya, meaning ' That which it is most sinful to slay ' (Balfour). * Monograph, p. 12.

But otherwise the modern Banjaras do not appear to retain any Sikh observances. "The Banjaras," Sir A. L}all writes/ "are terribly vexed 15. vvitch- by witchcraft, to which their wandcrin<^ and precarious exist- '^'^'^ cnce especially exposes them in the shape of fever, rheuma- tism and dysentery.

Solemn inquiries are still held in the wild jungles where these people camp out like gipsies, and many an unlucky hag has been strangled by sentence of their secret tribunals." The business of magic and witchcraft was in the hands of two classes of Bhagats or magicians, one good and the other bad," who may correspond to the Euro- pean practitioners of black and white magic. The good Bhagat is called Nimbu-katna or lemon -cutter, a lemon speared on a knife being a powerful averter of evil spirits. He is a total abstainer from meat and liquor, and fasts once a week on the day sacred to the deity whom he venerates, usually Mahadeo ; he is highly respected and never panders to vice. But the Janta, the ' Wise or Cunning Man,' is of a different type, and the following is an account of the devilry often enacted when a deputa- tion visited him to inquire into the cause of a prolonged illness, a cattle murrain, a sudden death or other misfortune.

A woman might often be called a Dakun or witch in spite, and when once this word had been used, the husband or nearest male relative would be regularly bullied into consulting the Janta. Or if some woman had been ill for a week, an avaricious ^ husband or brother would begin to whisper foul play. Witchcraft would be mentioned, and the wise man called in. He would give the sufferer a quid of betel, muttering an incantation, but this rarely effected a cure, as it was against the interest of all parties that it should do so. The sufferer's relatives would then go to their Naik, tell him that the sick person was bewitched, and ask him to send a deputation to the Janta or witch-doctor.

This would be at once despatched, consisting of one male adult from each house in the hamlet, with one of the sufferer's relatives. On the road the party would bury a bone or other article to 1 Asiatic Stttdies,\. p. Ii8(ed. 1899). produced from his Monograph. 2 Cumberlege, p. 23 et seq. The ^ His motive being the fine inflicted description of witchcraft is wholly re- on the witch's famih-.

test the wisdom of the witch-doctor. But he was not to be caught out, and on their arrival he would bid the deputation rest, and come to him for consultation on the following day. Meanwhile during the night the Janta would be thoroughly coached by some accomplice in the party. Next morning, meeting the deputation, he would tell every man all particu- lars of his name and family ; name the invalid, and tell the party to bring materials for consulting the spirits, such as oil, vermilion, sugar, dates, cocoanut, chironji} and sesamum.

In the evening, holding a lamp, the Janta would be possessed by Mariai, the goddess of cholera ; he would mention all particulars of the sick man's illness, and indignantly inquire why they had buried the bone on the road, naming it and describing the place. If this did not satisfy the deputation, a goat would be brought, and he would name its sex with any distinguishing marks on the body. The sick person's representative would then produce his iiazar or fee, formerly Rs. 25, but lately the double of this or more. The Janta would now begin a sort of chant, introducing the names of the families of the kuri other than that containing her who was to be proclaimed a witch, and heap on them all kinds of abuse. Finally, he would assume an ironic tone, extol the virtues of a certain family, become facetious, and praise its representative then present. This man would then question the Janta on all points regarding his own family, his connec- tions, worldly goods, and what gods he worshipped, ask who was the witch, who taught her sorcery, and how and why she practised it in this particular instance.

But the witch- doctor, having taken care to be well coached, would answer everything correctly and fix the guilt on to the witch. A goat would be sacrificed and eaten with liquor, and the deputation would return. The punishment for being proclaimed a Dakun or witch was formerly death to the woman and a fine to be paid by her relatives to the bewitched person's family. The woman's husband or her sons would be directed to kill her, and if they refused, other men were deputed to murder her, and bury the body at once with all the clothing and ornaments then on her person, while a further fine would be exacted from the family for not doing away with her themselves. 1 The fruil of Buchanania latifolia.

But murder for witchcraft has been almost entirely stopped, and nowadays the husband, after being fined a i^w head of cattle, which are given to the sick man, is turned out of the

village with his wife. It is quite possible, however, that an obnoxious old hag would even now not escape death, especi- ally if the money fine were not forthcoming, and an instance is known in recent times of a mother being murdered by her three sons. The whole village combined to screen these amiable young men, and eventually they made the Janta the

scapegoat, and he got seven years, while the murderers

could not be touched. Colonel Mackenzie writes that, " Curious to relate, the Jantas, known locally as Bhagats, in order to become possessed of their alleged powers of divina- tion and prophecy, require to travel to Kazhe, beyond Surat, there to learn and be instructed by low-caste Koli impostors."

This is interesting as an instance of the powers of witchcraft being attributed by the Hindus or higher race to the indi-

genous primitive tribes, a rule which Dr. Tylor and Dr.

Jevons consider to hold good generally in the history of magic. Several instances are known also of the Banjaras having i6. Human practised human sacrifice. Mr. Thurston states : ^ " In ^

former times the Lambadis, before setting out on a journey, used to procure a little child and bury it in the ground up

to the shoulders, and then drive their loaded bullocks over

the unfortunate victim. In proportion to the bullocks

thoroughly trampling the child to death, so their belief in a successful journey increased." The Abbe Dubois describes

another form of sacrifice :

"

" The Lambadis are accused of the still more atrocious crime of offering up human sacrifices. When they wish to

perform this horrible act, it is said, they secretly carry off the

first person they meet. Having conducted the victim to some lonely spot, they dig a hole in which they bury him up to the neck. While he is still alive they make a sort of lamp of dough made of flour, which they place on his head ; this they fill with oil, and light four wicks in it. Having done this, the men and women join hands and, forming a

1 Ethnographic Notes in Southern - Hindu Manners, Customs and India, p. 507, quoting from the Rev. Ceremonies, p. 70.

J.

Cain, Ind. Ant. viii. (1879).

17. Ad- mission of outsiders : circle, dance round their victim, singing and making a great noise until he expires." Mr. Cumberlege records ^ the fol- lowing statement of a child kidnapped by a Banjara caravan in I 87 I. After explaining how he was kidnapped and the tip of his tongue cut off to give him a defect in speech, the Kunbi lad, taken from Sahungarhi, in the Bhandara District, went on to say that, " The tdnda (caravan) encamped for the night in the jungle. In the morning a woman named Gangi said that the devil was in her and that a sacrifice must be made. On this four men and three women took a boy to a place they had made for puja (worship). They fed him with milk, rice and sugar, and then made him stand up, when Gangi drew a sword and approached the child, who tried to run away ; caught and brought back to this place, Gangi, holding the sword with both hands and standing on the child's right side, cut off his head with one blow. Gangi col- lected the blood and sprinkled it on the idol ; this idol is made of stone, is about 9 inches high, and has something sparkling in its forehead.

The camp marched that day, and for four or five days consecutively, without another sacrifice ; but on the fifth day a young woman came to the camp to sell curds, and having bought some, the Banjaras asked her to come in in the evening and eat with them. She did come, and after eating with the women slept in the camp. Early next morning she was sacrificed in the same way as the boy had been, but it took three blows to cut ofif her head ; it was done by Gangi, and the blood was sprinkled on the stone idol. About a month ago Sitaram, a Gond lad, who had also been kidnapped and was in the camp, told me to run away as it had been decided to offer me up in sacrifice at the next Jiuti festival, so I ran away." The child having been brought to the police, a searching and protracted in- quiry was held, which, however, determined nothing, though it did not disprove his story. The Banjara caste is not closed to outsiders, but the general rule is to admit only women who have been married to Banjara men. Women of the lowest and impure casteskidnapped children ^^^ cxcludcd, and for some unknown reason the Patwas " and and slaves. ' Monograph, p. 19. 2 The Patwas are weavers of silk thread and the Nunias are masons and navvies.

Nunias arc bracketed with these. In Nimar it is stated that formerly Gonds, Korkus and even Balahis ^ might become Banjaras, but this does not happen now, because the caste has lost its occupation of carrying goods, and there is therefore no inducement to enter it. In former times they were much addicted to kidnapping children—these were whipped up or enticed away whenever an opportunity presented itself during their expeditions.

The children were first put into the gotiis or grain bags of the bullocks and so carried for a few days, being made over at each halt to the care of a woman, who would pop the child back into its bag if any stranger passed by the encampment. The tongues of boys were sometimes slit or branded with hot gold, this last being the ceremony of initiation into the caste still used in Nimar. Girls, if they were as old as seven, were sometimes disfigured for fear of recognition, and for this purpose the juice of the marking-nut^ tree would be smeared on one side of the face, which burned into the skin and entirely altered the appearance. Such children were known as Jangar.

Girls would be used as concubines and servants of the married wife, and boys would also be employed as servants. Jangar boys would be married to Jangar girls, both remaining in their condition of servitude. But sometimes the more enterprising of them would abscond and settle down in a village. The rule was that for seven generations the children of Jangars or slaves continued in that condition, after which they were recog- nised as proper Banjaras. The Jangar could not draw in smoke through the stem of the huqqa when it was passed round in the assembly, but must take off the stem and inhale from the bowl. The Jangar also could not eat off the bell-metal plates of his master, because these were liable to pollution, but must use brass plates. At one time the Banjaras conducted a regular traffic in female slaves between Gujarat and Central India, selling in each country the girls whom they had kidnapped in the other.^ 1 An impure caste of weavers, rank- ^ Malcolm. Memoir of Central in;4 with the Mahars. India, ii. p. 296.

- Seniecarpns Anacardiuiii.

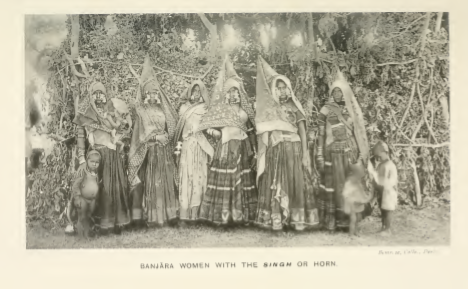

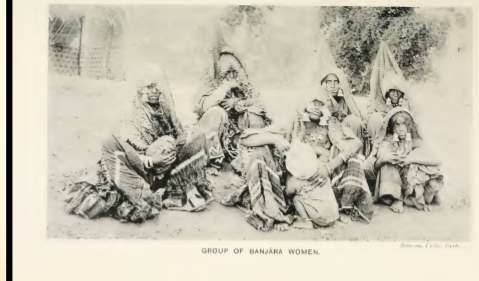

i8. Dress. Up to twelve years of age a Charan girl only wears a skirt with a shoulder-cloth tucked into the waist and carried over the left arm and the head. After this she may have anklets and bangles on the forearm and a breast -cloth. But until she is married she may not have the zudnkri or curved anklet, which marks that estate, nor wear bone or ivory bangles on the upper arm.^ When she is ten years old a Labhana girl is given two small bundles containing a nut, some cowries and rice, which are knotted to two corners of the dupatta or shoulder-cloth and hung over the shoulder, one in front and one behind. This denotes maidenhood. The bundles are considered sacred, are always knotted to the shoulder-cloth in wear, and are only removed to be tucked into the waist at the girl's marriage, where they are worn till death. These bundles alone distinguish the Labhana from the Mathuria woman. Women often have their hair hanging down beside the face in front and woven behind with silver thread into a plait down the back.

This is known as Anthi, and has a number of cowries at the end. They have large bell-shaped ornaments of silver tied over the head and hanging down behind the ears, the hollow part of the ornament being stuffed with sheep's wool dyed red ; and to these are attached little bells, while the anklets on the feet are also hollow and contain little stones or balls, which tinkle as they move. They have skirts, and separate short cloths drawn across the shoulders according to the northern fashion, usually red or green in colour, and along the skirt-borders double lines of cowries are sewn. Their breast-cloths are profusely ornamented with needle-work embroidery and small pieces of glass sewn into them, and are tied behind with cords of many colours whose ends are decorated with cowries and beads. Strings of beads, ten to twenty thick, threaded on horse-hair, are worn round the neck. Their favourite ornaments are cowries,' and they ' Cumberlege, p. i6. change for a rupee could not be had '^ Small double shells which are still in Chhattlsgarh outside the two prin- used to a slight e.Ktent as a currency in cipal towns. As the cowries were backward tracts. This would seem a form of currency they were prob- an impossibly cumbrous method of ably held sacred, and hence sewn carrying money about nowadays, but I on to clothes as a charm, just as have been informed by a comparatively gold and silver are used for orna- young official that in his father's lime, ments.

DKESS iS:

have these on their dress, in their liouses and on the trappinj^s of their bullocks. On the arms they have ten or

twelve bangles of ivory, or in default of this lac, horn or

cocoanut-shell. Mr. Ball states that he was "at once

struck by the peculiar costumes and brilliant clothing of these Indian gipsies. They recalled to my mind the appear- ance of the gipsies of the Lower Danube and Wallachia." ^ The most distinctive ornament of a Banjara married woman is, however, a small stick about 6 inches long made of the wood of the kJiair or catechu. In Nimar this is given to a woman by her husband at marriage, and she wears it after-

wards placed upright on the top of the head, the hair being wound round it and the head-cloth draped over it in a graceful fashion. Widows leave it off, but on remarriage adopt it again.

The stick is known as chunda by the Banjaras, but outsiders call it singh or horn. In Yeotmal, instead of one, the women have two little sticks fixed upright in the hair. The rank of the woman is said to be shown by the angle at which she wears this horn." The dress of the men presents no features of special interest. In Nimar they usually have a necklace of coral beads, and some of them carry, slung on a thread round the neck, a ^ Jtmgic Life in India, p. 516. ^ Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable contains the following notice of horns as an article of dress : " Mr. Buckingham says of a Tyrian lady, ' She wore on her head a hollow silver horn rearing itself up obliquely from the forehead. It was some four inches in diameter at the root and pointed at the extremity. This peculiarity re- minded me forcibly of the expression of the Psalmist : " Lift not up your horn on high ; speak not with a stiff neck.

All the horns of the wicked also will I cut off, but the horns of the righteous shall be exalted" (Ps. Ixxv. 5, 10).' Bruce found in Abyssinia the silver horns of warriors and distin- guished men. In the reign of Henry V. the horned headgear was introduced into England and from the effigy of Beatrice, Countess of Arundel, at Arundel Church, who is represented with the horns outspread to a great extent, we may infer that the length of the head -horn, like the length of the shoe -point in the reign of Henry VI., etc., marked the degree of rank.

To cut off such horns would be to degrade ; and to exalt and extend such horns would be to add honour and dignity to the wearer." Webb {Herit- age of Dress, p. 117) writes: "Mr. Elworthy in a paper to the British Association at Ipswich in 1865 con- sidered the crown to be a development from horns of honour. He maintained that the symbols found in the head of the god Serapis were the elements from which were formed the composite head-dress called the crown into which horns entered to a very great extent." This seems a doubtful speculation, but still it may be quite possible that the idea of distinguishing by a crown the leader of the tribe was originally taken from the antlers of the leader of the herd. The helmets of the Vikings were also, I believe, decorated with horns.

tin tooth-pick and ear-scraper, while a small mirror and comb are kept in the head-cloth so that their toilet can be performed anywhere. Mr. Cumberlege ^ notes that in former times all Charan Banjaras when carrying grain for an army placed a twig of some tree, the sacred nlui " when available, in their turban to show that they were on the war-path ; and that they would do the same now if they had occasion to fight to the death on any social matter or under any sup- posed grievance.

The Banjaras eat all kinds of meat, including fowls and pork, and drink liquor. But the Mathurias abstain from both flesh and liquor. Major Gunthorpe states that the Banjaras are accustomed to drink before setting out for a dacoity or robbery and, as they smoke after drinking, the remains of leaf-pipes lying about the scene of action may indicate their handiwork. They rank below the cultivating castes, and Brahmans will not take water to drink from them. When engaged in the carrying trade, they usually lived in kun's or hamlets attached to such regular villages as had considerable tracts of waste land belonging to them.

When the tdnda or caravan started on its long carrying trips, the young men and some of the women went with it with the working bullocks, while the old men and the remainder of the women and children remained to tend the breeding cattle in the hamlet. In Nimar they generally rented a little land in the village to give them a footing, and paid also a carrying fee on the number of cattle present. Their spare time was constantly occupied in the manufacture of hempen twine and sacking, which was much superior to that obtainable in towns. Even in Captain Forsyth's ^ time (1866) the construction of raihvays and roads had seriously interfered with the Banjaras' calling, and the}' had perforce taken to agriculture. Many of them have settled in the new ryotwari villages in Nimar as Government tenants. They still grow tilW^ in preference to other crops, because this oilseed can be raised without much labour or skill, and during their former nomadic life they were accustomed to

- Monograph, p. 40. ^ Author of the Niutar Settlement Report. 2 Melia indica. * Sesatmiiu.

sow it on any poor strip of land wliich they might rent for a season. Some of them also are accustomed to leave a part of tiieir holding untilled in memory of their former and more prosperous life. In many villages they have not yet built proper houses, but continue to live in mud huts thatched with grass. They consider it unlucky to inhabit a house with a cement or tiled roof; this being no doubt a superstition arising from their camp life. Their houses must also be built so that the main beams do not cross, that is, the main beam of a house must never be in such a position that if projected it would cut another main beam ; but the beams may be parallel.

The same rule probably governed the arrangement of tents in their camps. In Nimar they prefer to live at some distance from water, probably that is of a tank or river ; and this seems to be a survival of a usage mentioned by the Abbe Dubois : ^ " Among other curious customs of this odious caste is one that obliges them to drink no water which is not drawn from springs or wells. The water from rivers and tanks being thus forbidden, they are obliged in case of necessity to dig a little hole by the side of a tank or river and take the water filtering through, which, by this means, is supposed to become spring water." It is possible that this rule may have had its origin in a sanitary precaution.

Colonel Sleeman notes ^ that the Banjaras on their carrying trips preferred by-paths through jungles to the high roads along cultivated plains, as grass, wood and water were more abundant along such paths ; and when they could not avoid the high roads, they commonly encamped as far as they could from villages and towns, and upon the banks of rivers and streams, with the same object of obtaining a sufficient supply of grass, wood and water. Now it is well known that the decaying vegetation in these hill streams renders the water noxious and highly productive of malaria.

And it seems possible that the perception of this fact led the Banjaras to dig shallow wells by the sides of the streams for their drinking-water, so that the supply thus obtained might be in some degree filtered by percolation through the 1 Hindu Manners^ Citsloms and - Report on the Badhak or Bagri CercmoJiies, p. 21. Dacoits, p. 310.

intervening soil and freed from its vegetable germs. And the custom may have grown into a taboo, its underlying reason being unknown to the bulk of them, and be still practised, though no longer necessary when they do not

travel. If this explanation be correct it would be an

interesting conclusion that the Banjaras anticipated so far

as they were able the sanitary precaution by which our soldiers are supplied with portable filters when on the

march.

Each kuri (hamlet) or tdnda (caravan) had a chief or leader with the designation of Naik, a Telugu word meaning ' lord ' or ' master.' The office of Naik ^ was only partly hereditary, and the choice also depended on ability. The Naik had authority to decide all disputes in the communit}', and the only appeal from him lay to the representatives of Bhangi and Jhangi Naik's families at Narsi and Poona, and to Burthia Naik's successors in the Telugu country. As already seen, the Naik received two shares if he participated in a robbery or other crime, and a fee on the remarriage of a widow outside her family and on the discovery of a witch. Another matter in which he was specially interested was pig-sticking.

The Banjaras have a particular breed of dogs, and with these they were accustomed to hunt wild pig on foot, carrying spears. When a pig was killed, the head was cut off and presented to the Naik or head- man, and if any man was injured or gored by the pig in the hunt, the Naik kept and fed him without charge until he recovered. The following notice of the Banjaras and their dogs may be reproduced : '" " They are brave and have the reputation of great independence, which I am not disposed to allow to them. The Wanjari indeed is insolent on the road, and will drive his bullocks up against a Sahib or any one else ; but at any disadvantage he is abject enough. I remember one who rather enjoyed seeing his dogs attack me, whom he supposed alone and unarmed, but the sight of a cocked pistol made him very quick in calling them off, and very humble in praying for their lives, which I spared, ' Colonel Mackenzie's notes. - -Mr. W. !•'. Sinclair, C.S., in Ind. An/, iii. p. 1S4 {1S74).

II THK NAIK OR f/J'.A PMAN—HA NJARA DOGS 189

less for liis entreaties than because they were really noble animals. The Wanjaris arc famous for their doi^s, of which tiicre are three breeds. The first is a large, smooth dog, generally black, sometimes fawn-coloured, with a square

heavy head, most resembling the Danish boarhound. This is the true Wanjari dog. The second is also a large, square-headed dog, but shaggy, more like a great underbred spaniel than anything else. The third is an almost tailless greyhound, of the type known all over India by the various names of Lat, Polygar, Rampuri, etc.

They all run both by sight and scent, and with their help the Wanjaris kill a good deal of game, chiefly pigs ; but I think they usually keep clear of the old fighting boars. Besides sport and their legitimate occupations the Wanjaris seldom stickle at supplementing their resources by theft, especially of cattle ; and they are more than suspected of infanticide." The Banjaras are credited with great affection for their dogs, and the following legend is told about one of them : Once upon a time a Banjara, who had a faithful dog, took a loan from a Bania (moneylender) and pledged his dog with him as security for payment. And some time afterwards, while the dog was with the moneylender, a theft was com- mitted in his house, and the dog followed the thieves and saw them throw the property into a tank.

When they went away the dog brought the Bania to the tank and he found his property. He was therefore very pleased with the dog and wrote a letter to his master, saying that the loan was repaid, and tied it round his neck and said to him, * Now, go back to your master.' So the dog started back, but on his way he met his master, the Banjara, coming to the Bania with the money for the repayment of the loan. And when the Banjara saw the dog he was angry with him, not seeing the letter, and thinking he had run away, and said to him, ' Why did you come, betraying your trust ? ' and he killed the dog in a rage. And after killing him he found the letter and was very grieved, so he built a temple to the dog's memory, which is called the Kukurra Mandhi. And in the temple is the image of a dog. This temple is in the Drug District, five miles from

Balod. A similar story is told of the temple of Kukurra Math in Mandla. The following notice of Banjara criminals is abstracted from Major Gunthorpe's interesting account:^ "In the palmy days of the tribe dacoities were undertaken on the most extensive scale.

Gangs of fifty to a hundred and fifty well-armed men would go long distances from their tdndas or encampments for the purpose of attacking houses in villages, or treasure-parties or wealthy travellers on the high roads. The more intimate knowledge which the police have obtained concerning the habits of this race, and the detection and punishment of many criminals through approvers, have aided in stopping the heavy class of dacoities formerly prevalent, and their operations are now on a much smaller scale. In British territory arms are scarcely carried, but each man has a good stout stick {gedi), the bark of which is peeled off so as to make it look whitish and fresh.

The attack is generally commenced by stone -throwing and then a rush is made, the sticks being freely used and the victims almost invariably struck about the head or face. While plundering, Hindustani is sometimes spoken, but as a rule they never utter a word, but grunt signals to one another. Their loin-cloths are braced up, nothing is worn on the upper part of the body, and their faces are generally muffled. In house dacoities men are posted at different corners of streets, each with a supply of well-chosen round stones to keep off any people coming to the rescue. Banjaras are very expert cattle- lifters, sometimes taking as many as a hundred head or even more at a time.

This kind of robbery is usually practised in hilly or forest country where the cattle are sent to graze. Secreting themselves they watch for the herdsman to have his usual midday doze and for the cattle to stray to a little distance. As many as possible are then driven off to a great distance and secreted in ravines and woods. If questioned they answer that the animals belong to landowners and have been given into their charge to graze, and as this is done every day the questioner thinks nothing more of it. After a time the cattle are 1 Azotes on Criminal Tribes frequenting Bombay^ Berar and the Central Provinces (Bombay, 1882). II TIU'.IR VIRTUES igi quietly sold to individual purchasers or taken to markets at a distance.

The Banjfiras, however, are far from being wholly 22. Their criminal, and the number who have adopted an honest ^" "^^' mode of livelihood is continually on the increase. Some allowance must be made for their having been deprived of their former calling by the cessation of the continual wars which distracted India under native rule, and the extension of roads and railways which has rendered their mode of transport by pack - bullocks almost entirely obsolete. At one time practically all the grain exported from Chhattlsgarh was carried by them. In 1881 Mr. Kitts noted that the number of Banjaras convicted in the Berar criminal courts was lower in proportion to the strength of the caste than that of Muhammadans, Brahmans, Koshtis or Sunars,^ though the offences committed by them were usually more heinous.

Colonel Mackenzie had quite a favourable opinion of them : " A Banjara who can read and write is unknown. But their memories, from cultiva- tion, are marvellous and very retentive. They carry in their heads, without slip or mistake, the most varied and complicated transactions and the share of each in such, striking a debtor and creditor account as accurately as the best -kept ledger, while their history and songs are all learnt by heart and transmitted orally from generation to generation. On the whole, and taken rightly in their clannish nature, their virtues preponderate over their vices.

In the main they are truthful and very brave, be it in war or the chase, and once gained over are faithful and devoted adherents. With the pride of high descent and with the right that might gives in unsettled and troublous

times, these Banjaras habitually lord it over and contemn the settled inhabitants of the plains. And now not having foreseen their own fate, or at least not timely having read

the warnings given by a yearly diminishing occupation,

which slowly has taken their bread away, it is a bitter pill for them to sink into the ryot class or, oftener still, under stern necessity to become the ryot's servant. But they are settling to their fate, and the time must come when

' Berar Census Report (iSSi), p. 1 51.

all their peculiar distinctive marks and traditions will be