Attappadi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Infant Mortality Rate, 2016

Jeemon Jacob , Unborn Legacies “ India Today “ 24/11/2016

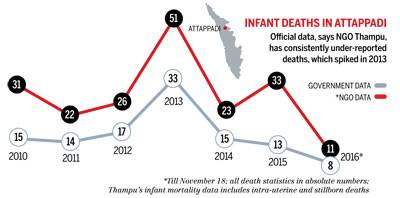

The grave was small, barely two feet deep. Pazhaniswami consigned the shrouded body of his seven-month-old grandchild Prayaga into the hole as his grieving family looked on. The setting for this solemn ceremony on October 1 was Attappadi, a forest paradise nestled in the mist-soaked valley in the Nilgiri hills of the Western Ghats. For the past six years, death has stalked the tribal hamlets of this administrative block in Palakkad district. Prayaga was among the latest of the 123 babies who have died since 2010. The 2016 figures are still being contested, but the first two weeks of November saw three casualties. The Attappadi deaths first raised a storm in 2013, seen as an anachronism in a state with India's lowest infant mortality rate (IMR). Only 12 infants die for every 1,000 born in Kerala (the national average is 40 deaths).

The official data for up to November 18 says the figure is eight deaths (NGO Thampu puts the figure at 11) but then it also mentions six intra-uterine foetal deaths. The official count of abortions is 26, but that could be much higher as just one hospital, the Kottathara Tribal Speciality Hospital which handles around 30 per cent of the pregnancy cases in the area, has reported 23 so far this year. Seen together with the fact that this year has seen only 735 births so far in Attappadi's three panchayats, and infant mortality statistics for the area are sure to be a blot again in the Kerala health department's records.

Today, tribals constitute just 34 per cent of Attappadi's total population, around 33,500 people in 192 villages. Of the three major tribal subgroups, Irulas make up nearly 80 per cent of this population. Health assessment reports in 2014 by paediatric surgeon Dr E.K. Sathyan and his team found that a majority of the pregnant women were anaemic and, consequently, a vast number of newborns were underweight with stunted growth. Indeed, malnutrition among tribal women is the prime factor for infant deaths in Attappadi. Ironically, this has occurred in a period when the state's attention to tribal welfare has markedly intensified. No less than 26 state departments are implementing projects worth Rs 520 crore, enough to pay each of the 9,433 tribal families over Rs 5 lakh in cash. There is a Rs 100 crore project to build 2,950 houses for them, Rs 76.13 crore for 16 new roads, Rs 100 crore under the National Rural Livelihood Mission, another Rs 100 crore to provide free provisions for seven years and Rs 43.35 crore under the National Health Mission for medical care. Since 2011, around 3,229 houses have been sanctioned under the Integrated Tribal Development Project. This is not counting the free food packets, free lunches and free Onam festival kits.

So why are the tribals still in such a state? Infants continue to die, the men are ravaged by unemployment and alcoholism, and malnutrition is at crisis levels. Planning Board member Dr B. Eqbal warns of a "silent genocide due to the criminal neglect of officials and Kerala society's apathy". "The programmes have not improved the situation," he says ruefully.

Every infant death seems to unearth more damning findings. A health check-up of 567 students of the Sholayar Tribal Higher Secondary school-after the death of 13-year-old Manikandan on September 7-found 110 of them were acutely anaemic.

Locals, however, say district health authorities simply pass on the blame to the tribals. "After every infant death, officials file a report saying the pregnant mother and family were reluctant to go to hospital for delivery and refused to seek medical help," says K.A. Ramu, a tribal activist.

The state's response has been to increase its welfare street strength. Some 145 Scheduled Tribe promoters, 179 animators, 125 anganwadi teachers, 125 helpers and 65 ASHA workers have been deployed to monitor the developmental works. In 2013, 102 new health posts were added, including 15 doctors. "There are seven health officials for every pregnant woman in the region," says Ramu. "But the tribals still deliver dead babies."

K.N. Ramesh, an activist from the Kallanmala colony, alleges an official-contractor-politician nexus who have benefitted from the mega development works. "In our death lies their prosperity," he says. Meanwhile, those in power go to astounding lengths to evade blame. Recently the Left Front's tribal development minister A.K. Balan told the assembly that one case was an abortion. But since the pregnancy "happened during the previous UDF regime's reign", he "was not responsible for that".

Kerala chief secretary S.M. Vijayanand, who worked in Attappadi as project officer in the mid-1980s, admits to a "systemic failure". "Delivery can be improved only through constant vigil and social auditing on programme implementation. Officials are taking a pro-active role. There have been improvements," he says.

In 2014, P.B. Nooh, sub-collector of Ottappalam,was appointed nodal officer for tribal development in Attappadi. Nooh had organised coaching classes for tribal children to help them get admission in the Sainik School in Thiruvananthapuram, a move that saw seven of them get into the school. He admits it's an uphill task. "Attappadi remains a Bermuda triangle for development," he says. Nooh links the tribal deaths to the loss of land and the destruction of their traditional methods of farming. Today, they mostly graze cattle and work as labourers in state programmes like NREGA. The Integrated Tribal Development Survey says only 1,309 acres of an original 10,796 acres of land have been returned to the tribals (settlers from the plains now control most of this land, having duped the illiterate tribals with petty cash or liquor). Nooh had identified 1,300 landless families and allocated 517 of them an acre each of cultivable land. But titles could not be issued as other departments didn't cooperate. Today, there are over 4,000 land dispute cases in Attappadi. The tribals have been fighting for their land for the last 30 years. Meanwhile, they continue to bury their dead in the soil.

Umbrella production

Tribal women of Attappady are trying to make their presence felt in the umbrella market

A set of tribal women from Attappady are attempting to make their presence felt in the seasonal umbrella market, dominated by big players, with quality products in various colours and designs.

A 60-member collective of tribal women from various settlements are making over 10,000 umbrellas targeting school and college students across Kerala at the start of the academic year.

Their Karthumbi brand of umbrellas had a humble beginning last year with a modest production of 800 umbrellas. Tribal voluntary organisation Thmabu and Peace Collective, a social media initiative of overseas Malayalees, are supporting the group. The Scheduled Tribes Department is extending financial support to the initiative.

“Though rain continues to elude the rain-shadow Attappady, we are fast making the umbrellas to ensure a big sale during the school-opening season. Most of us who are involved in umbrella-making never owned any umbrellas. We used to take refuge under canopies till the rain got over,” said B. Lakshmi of the Dasannur tribal settlement, who mastered umbrella-making two years ago.

The Hindu carried an article on Karthumbi last year and a number of individuals have approached Thambu, offering to buy the products since then. The C-DAC Recreation Club in Thiruvananthapuram has ordered 100 umbrellas.

Financial support

It was Peace Collective that ensured the working capital last year. Some of its members extended interest-free loans up to ₹10,000. “After selling the umbrellas, the tribal women were able to repay the loans. This year, the collective is promising more financial help,” said K.A. Ramu of Thambu.

Each beneficiary gets a daily wage of ₹600. Sneha Edamini of Peace Collective said it started engaging in the project after knowing about the high rate of poverty and malnutrition in the region.