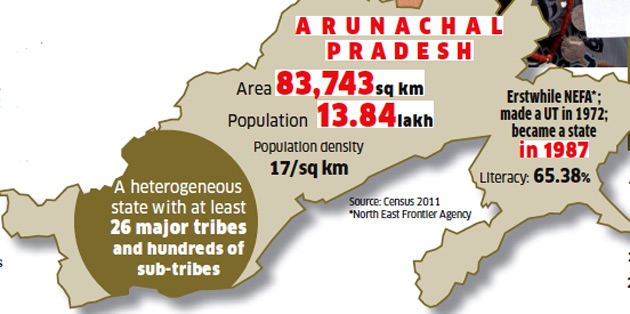

Arunachal Pradesh: Demographics/ Religion

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Citizenship

Chakmas and Hajongs

2022: Aborted plan to hold special census by the AP government

Rahul Karmakar, January 30, 2022: The Hindu

Chakmas and Hajongs | The peoples without a state

The Arunachal government’s aborted plan to hold a special census targeting Chakmas and Hajongs triggered concerns of their racial profiling

The often-violent Assam agitation from 1979 to 1985 had a domino effect on some of the other north-eastern States. The agitation, spearheaded by students, was aimed at expelling the “illegal immigrants” — by which they referred to “Bangladeshis” — who they claimed were outnumbering the indigenous communities.

The present-day hill States were fairly untouched by the riots in undivided Assam of the 1960s and early 1970s that targeted Bengalis through the politically-charged ‘Bongal kheda’ (chase out the Bengalis) campaign. In 1979, weeks after the Assam agitation started, the Bengalis of Shillong, Meghalaya, became the victims of the first major riot. Sporadic communal violence that continued till the 1990s did not spare the other non-tribal communities such as Biharis, Marwaris, Nepalis, Punjabis and Sindhis, viewed as “dkhars” (outsiders). The situation was the worst in 1987, which was marked by curfews throughout the year.

The Assam agitation also impacted Arunachal Pradesh and the politics of xenophobia was primarily directed at four communities — Chakmas, Hajongs, Tibetans and Yobins — who had settled there before Arunachal Pradesh was upgraded from the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) in 1972. These four communities were largely settled in the present-day Changlang district when NEFA was under the Ministry of External Affairs up to 1965 and then under the Ministry of Home Affairs until 1972.

The Yobins, formerly called Lisus, came from northern Myanmar. The migration of the Tibetans started in 1959 with the flight of the 14th Dalai Lama from Lhasa and peaked during the 1962 war with China. The main concentrations of the Tibetans today are in West Kameng and Tawang districts of Arunachal Pradesh.

The Buddhist Chakmas and the Hindu Hajongs came from present-day Bangladesh. Communal violence in 1964 and the construction of the Kaptai dam on the Karnaphuli River displaced about 100,000 Chakmas from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh. Around the same time, religious persecution made about 1,000 Hajongs cross over from Mymensingh district of Bangladesh. Some Chakmas were settled in areas of Mizoram and Tripura contiguous to the CHT.

The flow of Chakmas to Arunachal Pradesh continued till 1969. Those who came later were mostly from Bihar’s Gaya, where former Union Relief and Rehabilitation Minister Mahavir Tyagi had tried to settle them in. Over time, the Chakma-Hajongs became more of a political issue than a humanitarian problem in the State with indigenous groups mobilising on a plank of pushing back refugees.

Amid growing opposition to the continued settlement of Chakmas in the State, the Arunachal government had planned a special census from December 11 to 31, 2021, leading to criticism that Chakmas and Hajongs were being subjected to “racial profiling. The census was put on hold after the Chakma Development Foundation of India (CDFI) approached the Prime Minister’s Office. But it remains a sensitive political issue in the State.

‘Refugees go back’

Documents with the Committee for Citizenship Rights of the Chakmas and Hajongs of Arunachal Pradesh (CCRCHAP) show that New Delhi had granted migration certificates to about 36,000 Chakmas and Hajongs settled in the erstwhile NEFA. These certificates indicated legal entry into India and the willingness of the Centre to accept the migrants as future citizens. But indigenous groups led by the All Arunachal Pradesh Students’ Union (AAPSU) said the papers were inconsequential since neither the local people nor their representatives were consulted before settling the refugees in their backyard. They also pointed out that the prolonged stay of the refugees violated the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation (BEFR) of 1873 that requires outsiders to visit the State with a temporary travel document called Inner the Line Permit, also applicable in Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland.

The Chakma-Hajongs were at the core of the first bandh that Arunachal Pradesh experienced in April 1980. The AAPSU had imposed the shutdown to highlight a few demands, including resolution of the Assam-Arunachal boundary problem, detection and deportation of foreign nationals from the State and withdrawal of land allotment permit and trade licence from the non-Arunachalees. Inspired by the Assam agitation, the AAPSU organised a series of district-level bandhs in August 1982, primarily demanding the ouster of “outsiders”. In 1985, the government-backed students’ body adopted a resolution for asking the Centre to immediately remove the refugees settled permanently in the State and take steps against a possible influx of people displaced internally by the anti-foreigners agitation in adjoining Assam.

The ‘refugees go back’ slogans returned after a lull in 1994 when the AAPSU organised a march to Delhi, demanding action against “illegal foreign nationals”, who, they claimed, were threatening to change the demography of the region. Pointing out that the Indian government violated the legal provisions prohibiting people from outside entering Arunachal Pradesh, the AAPSU organised a ‘people’s referendum rally’ in September 1995 against making the State a “dumping ground” for “foreigners”. December 31 that year was set as the deadline for the then Congress government to eject the refugees, compelling the Centre to form a high-level committee to look into the issue.

According to Chakma organisations, the State government had by then systematically denied the refugees access to social, economic and political rights they were entitled to under Indian and international laws. The employment of Chakmas and Hajongs was banned in 1980 and all trade licences issued to then in the 1960s were seized in 1994. There were reports of blockades and attacks on the refugee camps and Vijoypur, a village in the Changlang district, was reportedly destroyed thrice between 1989 and 1995. In September 1994, the State government allegedly began a campaign to close down schools in the refugee areas and to relocate the Chakma-Hajongs.

Deportation bid

The AAPSU flagged the increasing population of the Chakma-Hajongs to justify the perceived threat to the identity and culture of the indigenous people. It said the population of the refugees had by the new millennium swollen to 65,000 from the 57 families originally settled in the State after a temporary stay in Assam’s Ledo in 1964. “Their population is more than 1 lakh today,” AAPSU’s general secretary Tobom Dai said. However, Santosh Chakma, general secretary of the CCRCHAP, said the figure was exaggerated. “A special census of the Chakma-Hajongs conducted in 2010-11 revealed the population was under 50,000. According to our estimate, it is about 60,000 now with 95% of them born in India to merit citizenship under Section 3 of the Citizenship Act,” he said.

The State government’s aborted move to hold the special census followed Chief Minister Pema Khandu’s Independence Day speech in which he said “all illegal immigrant Chakmas will be moved and settled in some other places” as the Constitution does not allow them to live in a tribal State. Following the controversies, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has asked the Ministry of Home Affairs and the State government to submit a report on the alleged racial profiling of the Chakmas and Hajongs.

The Chakma Development Foundation says there is no provision in the Constitution as a tribal State that stops the Chakmas from staying in Arunachal Pradesh. It also said the government has not processed their citizenship applications despite the Supreme Court’s orders in 1996 and 2015 to do so. The solution, Chakma organisations said, lies in the State respecting the rule of law and the judgments of the Supreme Court and the politicians stopping using the Chakma-Hajong issue for political benefits.

Religion

2001

Religion returns in Indian census provide a wonderful kaleidoscope of the country s rich social composition, as many religions have originated in the country and few religions of foreign origin have also flourished here. India has the distinction of being the land from where important religions namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism have originated at the same time the country is home to several indigenous faiths tribal religions which have survived the influence of major religions for centuries and are holding the ground firmly Regional con-existence of diverse religious groups in the country makes it really unique and the epithet unity in diversity is brought out clearly in the Indian Census.

Ever since its inception, the Census of India has been collecting and publishing information about the religious affiliations as expressed by the people of India. In fact, population census has the rate distinction of being the only instrument that collets the information son this diverse and important characteristic of the Indian population.

| Religion |

Number

|

%

|

| All religious communities |

1,028,610,328

|

100.0

|

| Hindus |

827,578,868

|

80.5

|

| Muslims |

138,188,240

|

13.4

|

| Christians |

24,080,016

|

2.3

|

| Sikhs |

19,215,730

|

1.9

|

| Buddhists |

7,955,207

|

0.8

|

| Jains |

4,225,053

|

0.4

|

| Others |

6,639,626

|

0.6

|

| Religion not stated |

727,588

|

0.1

|

| Source : Religion, Census of India 2001 | ||

At the census 2001, out of 1028 million population, little over 827 million (80.5%) have returned themselves as followers of Hindu religion, 138 million (13.4%) as Muslims or the followers of Islam, 24 million (2.3%) as Christians, 19 million (1.9%) as Sikh, 8 million (0.80%) as Buddhists and 4 million (0.4%) are Jain. In addition, over 6 million have reported professing other religions and faiths including tribal religions, different from six main religions.

Hinduism is professed by the majority of population in India. The Hindus are most numerous in 27 states/Uts except in Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Lakshadweep, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Jammu & Kashmir and Punjab.

The Muslims professing Islam are in majority in Lakshadweep and Jammu & Kashmir. The percentage of Muslims is sizeable in Assam (30.9%), West Bengal (25.2%), Kerala (24.7%), Uttar Pradesh (18.5%) and Bihar (16.5%).

Christianity has emerged as the major religion in three North-eastern states, namely, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Meghalaya. Among other states/Uts, Manipur (34.0%), Goa (26.7%), Andaman & Nicobar Islands (21.7%), Kerala (19.0%), and Arunachal Pradesh (18.7%) have considerable percentage of Christian population to the total population of the State/UT.

Punjab is the stronghold of Sikhism. The Sikh population of Punjab accounts for more than 75 % of the total Sikh population in the country. Chandigarh (16.1%), Haryana (5.5%), Delhi (4.0%), Uttaranchal (2.5%) and Jammu & Kashmir (2.0%) are other important States/Uts having Sikh population. These six states/Uts together account for nearly 90 percent Sikh population in the country.

The largest concentration of Buddhism is in Maharashtra (58.3%), where (73.4%) of the total Buddhists in India reside. Karnataka (3.9 lakh), Uttar Pradesh (3.0 lakh), west Bengal (2.4 lakh) and Madhya Pradesh (2.0 lakh) are other states having large Buddhist population. Sikkim (28.1%), Arunachal Pradesh (13.0%) and Mizoram (7.9 %) have emerged as top three states in terms of having maximum percentage of Buddhist population.

Maharashtra, Rajsthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujrat, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi have reported major Jain population. These states/Uts together account for nearly 90 percent of the total Jain population in the country. The percentage of Jain population to the total population is maximum in Maharastra (1.3%), Rajsthan (1.2%), Delhi (1.1%) and Gujrat (1.0%). Elsewhere in the country their proportion in negligible.

2011

As per census 2011, Christian are majority in Arunachal Pradesh state. Christian constitutes 30.26% of Arunachal Pradesh population. In all Christian form majority religion in 4 out of 16 districts of Arunachal Pradesh state. The data for 2020 & 2021 is under process and will be updated in few weeks.

Muslim Population in Arunachal Pradesh is 27.05 Thousand (1.95 percent) of total 13.84 Lakhs. Christian Population in Arunachal Pradesh is 4.19 Lakhs (30.26 percent) of total 13.84 Lakhs.

Hindu are minority in Arunachal Pradesh state forming 29.04% of total population. Hinduism is followed with majority in 3 out of 16 districts.

|

Religion |

Percentage |

|

Hindu |

29.04% |

|

Muslim |

1.95% |

|

Christian |

30.26% |

|

Sikh |

0.24% |

|

Buddhist |

11.77% |

|

Jain |

0.06% |

|

Other Religions |

26.20% |

|

Not Stated |

0.48% |

Districts - Religion 2011

Arunachal Pradesh District Wise Data - Religion 2011

| District | Majority Religion |

|---|---|

| Papumpare | Christian |

| Changlang | Buddhist |

| Lohit | Hindu |

| West Siang | Others |

| Tirap | Christian |

| East Siang | Others |

| Kurung Kumey | Christian |

| West Kameng | Buddhist |

| Upper Subansiri | Others |

| Lower Subansiri | Others |

| East Kameng | Christian |

| Lower Dibang Valley | Hindu |

| Tawang | Buddhist |

| Upper Siang | Others |

| Anjaw | Hindu |

| Dibang Valley | Others |

Literacy

|

# |

District |

Literacy |

|

1 |

Serchhip |

97.91% |

|

2 |

Aizawl |

97.89% |

|

3 |

Mahe |

97.87% |

|

4 |

Kottayam |

97.21% |

|

5 |

Pathanamthitta |

96.55% |

The Christians

Population on the rise

Samarth Bansal and Smriti Kak Ramachandran, March 9, 2017: The Hindustan Times

Christian population in Arunachal Pradesh rose from less than 1% in 1971 to more than 30% in 2011, official census data show, numbers which appear to back Union minister Kiren Rijiju’s controversial comments about a radical demographic change in the northeastern state.

Manipur, another state in the region, also saw Christian population rise from around 19% in 1961 to more than 41% in 2011, census data showed.

Rijiju had sparked a controversy after referring to the growing Christian numbers in Arunachal Pradesh – his home state -- and linking them to conversions. “Hindu population is reducing in India because Hindus never convert people,” he had said.

However, there is no clear official reason for the rise in the Christian population in these states. While Rijiju cited religious conversion as a possible reason, some experts say this could be because of migration.

Opposition parties had slammed Rijiju for his comments and the Congress had accused the BJP of “converting Arunachal into a Hindu state”.

Arunachal Pradesh

In Arunachal Pradesh, the biggest state in the region, the share of ‘Other Religions’ category which comprised of two-thirds of Arunachalis in 1971 dropped to 26% in 2011 from as much as 64% in four decades ago.

Other religions include tribal faiths including the indigenous Donyi-Polo (Sun and Moon) whose followers worship the celestial objects.

The decadal growth rate of Christian population in the state has been more than 100% all through.

The population of Arunachal Pradesh is 1.3 million, according to the 2011 census.

Manipur

In Manipur, with a population of 2.8 million, the Christian numbers have surged.

Hindus constituted around 62% share of the Manipuri population in 1961 while Christians had a 19% share. In 2011, both Christians and Hindus have almost equal share — around 41%.

Taken together, the two states constitute just 0.3% of the Indian population. Further, total Christian population stands at 2.78 crore, around 2%.

For the R S S, these findings buttress their claims and concerns of an imbalance in growth rates and the so-called shrinking of Hindu population.

“As the Census figures show, there is a huge disparity in the way the Christian population has grown and the Hindu population has shrunk. There is no denying the role of missionaries who convert people in this. But off late there is an awakening of the indigenous people and the Sangh is only making them aware of this (conversions),” Arunachal unit state secretary of the R S S Nido Sakter told HT.

JK Bajaj of the Centre for Policy Studies also said the growth of Christianity is the result of “aggressive proselytisation undertaken by the Church mainly in the period following Independence”.

In Arunachal Pradesh, there have been regular reports of conversions by force, especially among the Nocte and the Wancho tribes, he said.

Not all agree that conversion alone is responsible for the growth of Christian population.

Amitabh Kundu, professor at Institute for Human Development, said migration could be another reason.

“One needs to take a closer look at migration figures from the Census and check how much of this increase can be attributed to in-migration of Christians from other states before drawing conclusions.”

He, however, added that since “literacy rate of Christians is higher than other religious groups, which means their fertility rate would be low”.

“Hence, natural growth cannot alone explain this increase, which points to conversion as a possible explanation.”

An R S S functionary who has earlier served in Manipur also said that migration of Christians from other states is a contributing factor.

He also raised concerns over the census enumeration, pointing out that in certain far-flung areas, some tribes have been incorrectly listed as Christians.

Resistance to conversion

Prerna Katiyar, Nov 19, 2017: The Economic Times

From: Prerna Katiyar, Nov 19, 2017: The Economic Times

From: Prerna Katiyar, Nov 19, 2017: The Economic Times

From: Prerna Katiyar, Nov 19, 2017: The Economic Times

From: Prerna Katiyar, Nov 19, 2017: The Economic Times

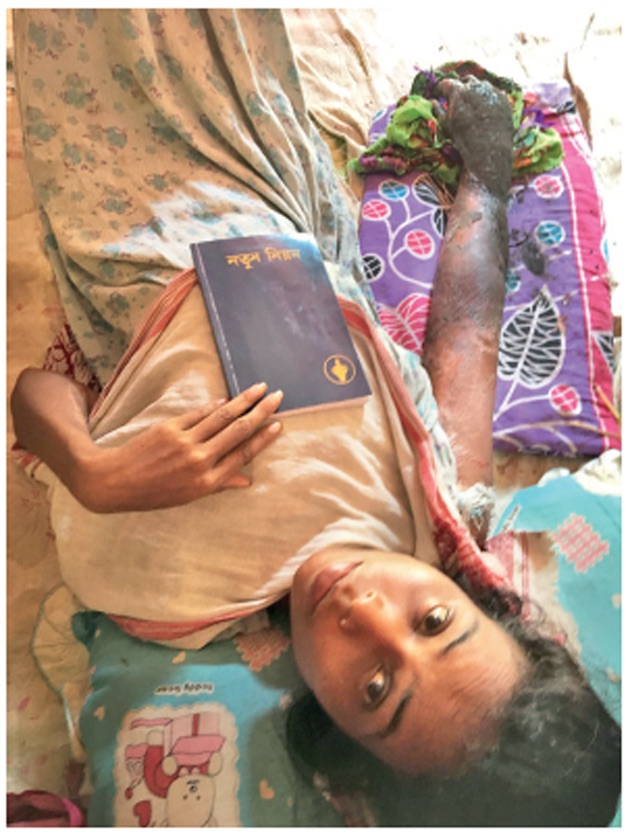

CHANGLANG, PAPUMPARE & ANJAW: Arunachal Pradesh Sona Padam is writhing in pain. The 20-year-old who got married last year has a rare skin disease on her right arm that has blackened the skin and swollen it to an extent that she cannot use “The Hindus have done this to me, my in-laws, my own people. They got this done through an occultist,” she alleges.

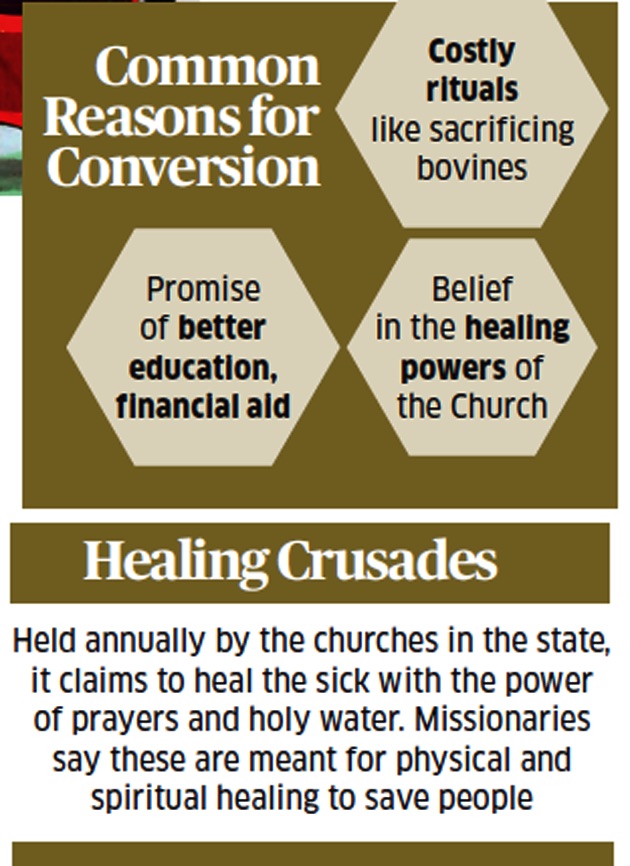

Sona is an Adi tribal from Arunachal Pradesh, a state that is home to 26 major tribes and more 100 sub-tribes. Taboos, superstitions and rituals prevail, and sacrificing bovines for the most minor of ailments is par for the holy course.

Sona’s parents, too, resorted to such sacrifices to help her heal but without luck. “We almost become bankrupt because of such rituals,” shrugs her mother, a traditional weaver, sitting at Sona’s bedside with a hand fan.

Today, Sona is recuperating at the Tangsa Baptist Churches Association’s Bethel Prayer Centre at Jairampur, a town in the Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh — with a prayer on her lips and The New Testament in her hands. “Jesus will heal me. I am told the holy water they are giving me has divine powers,” she says.

To be sure, the promise of “healing power of Christ” and the prospects of better education have been driving the believers of indigenous faiths in Arunanchal towards Christianity. It’s been happening for some time now, with visible results. The difference today, though, is the current climes. A government buoyed by the platform of Hindu nationalism rules in both the state and the Centre. And at the helm of the saffron ship is the ideological and organisational big brother, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (R S S).

“The missionaries’ work is a national threat. Indigenous faith will have to be taken forward. The Sangh has been successful in supporting and inspiring these movements. Self-awareness is key for realisation of where they come from,” says Sandeep Kavishwar, R S S pracharak, and joint organising secretary, Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram (NE), a service arm of the Sangh working in tribal areas. The church, of course, has a different take. Christian missionaries were not allowed to enter Arunanchal decades ago, points out Tame Hakam, a pastor at the Catholic Church of Itanagar. Tribals of Arunachal went to Assam in the 1950s and 1960s for education, he adds. “We were poor and illiterate till then. When they came back, the first Church was built at Ziro (in Lower Subansiri district).

It is the church that taught us to preserve our dialect and language.” The past three-four decades have been productive for the church. Consider: In the 1981 Census, followers of indigenous faiths (termed as Others in the census) were a little over half of the population, at 51.6%. By 2011, it was down to 26%, according to the most recent census.

The Christian population — largely Roman Catholics —incontrast has surged from 0.79% in 1971 to 31% by 2011, in the process becoming the largest religion. Hindus come in at 29%, unimaginable for the Hindu nationalists, and for many within the BJP and the R S S. “The Hindu population is reducing in India because Hindus never convert people,” Union Minister for State for Home Affairs Kiren Rijuju had famously said on his home turf in February.

AMIK MATAI: An indigenous movement that believes in the workshop of nature. It is followed by Digaru and Mishmi tribes

The missionaries for their part will point to another set of statistics: the 1951 census showed 0% Christians and 0% literacy. The literacy rate is 65.38%, as per Census 2011.

Bible-reading, Tribal Style

The main prayer hall of Bethel Prayer Centre has scores of converted tribals following biblical recital of “the mother”. “We preach in the language they understand. We were praying for peace, harmony, security and health of the entire nation,” says R Jujuli, the mother. Liturgical services at most of the Arunachal churches are not conducted by priests but by young converts who work as catechists.

Established in 2009, the Bethel Prayer Centre serves asadeaddiction centre and offers free accommodation, counselling and prayers to the ailing and the infirm. “The missionaries do not ask us to practise costly rituals or change our lifestyles, languages or even our wardrobe. Many of the converted tribals, like me, have not even been asked to change names. We have received the gospel of Jesus, enlightenment, education. My own Nyishi tribesmen were rude, uncultured and a warrior tribe. The church has made us better people. What is wrong in that?” asks Hakam, the pastor, who calls himself a Nyishi Christian and refuses to call Christianity a foreign religion. “Christianity was born in Central Asia.

How can it be foreign?” Hakam’s faith appears unshakeable, particularly when it comes to healing crusades. “Once, a woman came with crippled legs; we all prayed for her and she was cured. A tribal woman who was told by doctors she will never bear children had twins once she became a Christian and attended a healing crusade.” So is medical science futile? “Miracles happen. It is all a matter of faith,” avers Hakam. It isn’t as if all tribals are enthusiastic about conversion. Many believe this has been at the cost of indigenous customs, beliefs and cultures.

“Missionaries offer medicine, food grain and cash to the needy on the back of strong funding from outside. Earlier, we were all one. There was no disharmony. But now converted tribals — our own brethren till a couple of years back — look down upon us,” says N Songtheng, a Lisu tribal working for the preservation of indigenous faith. Hindu organisations clearly a see a nefarious plan in the missionary work. “They are working for conversion; we are working for education. Their plans are treacherous… Tribal culture ought to be preserved with the same zeal that missionaries display while converting tribals,” says Bindu Nair, a Hindi teacher at Vivekananda Kendra Vidyalaya, Changlang.

The photograph of a former R S S sahkaryavah Eknath Ranade — often called the underground sarsangh chalak for his activities when the Sangh was banned in the wake of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination — hangs on a wall of the staff room alongside Swami Vivekananda’s.

As does the BJP government. In August, the state cabinet approved the establishment of the Department of Indigenous Faith & Cultural Affairs (DIFCA) at a meeting chaired by Chief Minister Pema Khandu. “The indigenous communities of the state are getting disconnected from their rich culture and languages due to globalisation and exposure to external influences.

As such, there have to be specific steps to preserve and protect them from disappearing into oblivion,” the CM said. But the Christian community was quick to smell an agenda. Toko Teki, general secretary of the Arunachal Christian Forum (ACF) said the move to create such a department was targeted at the Church. “The locals were getting attracted to Christianity due to various local problems...The government should not interfere in religious matters and treat all religious groups equally,” Teki asserted.

Bowing to the pressure of the Christian community, the cabinet decided to drop the word “faith” from the proposed department. A Facebook page titled “Fight for Tribals Tradition” has been created to garner support for the new department. Hundreds of photos with tribals holding placards — such as “My name is Khojjon Sumta. I am from Tangsa community, district Changlang. I strongly support DIFCA” — have been posted.

Tribal disdain for the missionaries isn’t difficult to spot. “They call us shaitan (demon), our roots rotten. They scorn at us and convert innocent tribals either by allurement, force or coercion,” says Tajom Tasung, the newly elected president of Indigenous Faith and Cultural Society of Arunachal Pradesh from the Donyi-Polo faith. Others even claim missionaries have a nexus with Naga terrorists who support them in their mission in return for moolah.

The church duly rubbishes the allegations. “People who put such blame on us are bad spirits. Christianity or Christian preachers never force anyone to convert. Christ is the saviour of mankind. It’s only through our preaching that people are convinced, never by force, coercion or allurement,” says Reverend Dr Nyakdo Tasar, president, Arunachal Pradesh Christian Revival Church Council. Tasar points to the changed living conditions of tribals to illustrate the good work of the Church. “Tribals of Arunachal led lives like animals. But when the messengers of Christ came to the state, there was a remarkable change in their living style. Ask anyone here what was their lifestyle before the missionaries entered the state and how they lead their life now.”

The line between altruism and enticement is often not too thick. “The moment they come to know of a sick person, they approach his home and make him change religion, often offering money for conversion,” alleges Kanzai Taisam, a youth leader working for the revival of indigenous faith in Arunachal.

Even as Arunachal is the largest state in the Northeast, it has just 14 hospitals and 18 degree colleges across its 21 districts. The anti-conversion legislation of 1978 aimed at curbing conversions and a refusal to issue inner-line permits — mandatory for outsiders entering the state — don’t deter Christian missionaries. “The anti-conversion law was never enforced as its rules have not been framed,” says Kavishwar.

A prevalent perception — and not just in the Northeast — is that the Congress and its policy of appeasing minorities may have contributed to the strides taken by the missionaries. Arunachal Pradesh BJP president Tapir Gao attributes the high conversion to poverty, innocence, lack of education and medical facilities and the catalytic work of the Congress. At the same time he stresses on the need for preservation of indigenous faiths. “The Arunachal Pradesh Congress Committee has had a long history in being a catalyst for reducing the indigenous population.

The tribals were innocent people but now I feel people are more aware. There is a resurrection of indigenous faith; many are coming back to their tribal fold — which is a good thing,” adds Gao. Gegong Apang, the longest serving Congress CM of the state — he is now with the BJP — refuses to acknowledge such allegations. “Charges of giving a free hand to missionaries are baseless,” he told ET Magazine.

Lately, followers of three indigenous faiths — Donyi-Polo, Rangfraa and Amik Matai — have been making efforts to stop conversions and save their native culture.

They are also bringing about reforms to age-old practices such as saying no to sacrifices and engaging youth to spread the movement. The first active indigenous faith movement was started in 1986 by Talom Rukbo in whose memory December 1 is celebrated as Indigenous Faith Day or Religious Freedom Day. “Rather than working separately, we are working to unify the three indigenous faiths, which would make them more powerful in taking on the mighty church,” explains Khomseng Khomrang, a religious leader of Rangfraa movement from Changlang. The Rangfraa is an animist belief system of Arunachal. Changes are becoming evident owing to the small yet significant steps being taken. Against the many and big edifices of churches, one finds small “ganggin” or places of worship of indigenous faith. There are 450 such places across the state.

Does the Sangh plan ghar wapsi for converted tribals to bring them back into the fold of Hinduism? “Hindus’ mentality is not for conversion. We believe in positive affirmation and not conversions. It is for the people to realise what is happening to them and stop getting converted. We are working as a catalyst to create that awareness to help them return to their tribal roots and nothing more,” says Kavishwar.

Christian preachers never force anyone to convert: Dr Nyakdo Tasar

Excerpts from an interview with Reverend Dr Nyakdo Tasar, president, Arunachal Pradesh Christian Revival Church Council:

How do you react to charges that Christian missionaries convert forcibly and resort to allurement?

That is false. Christian preachers never force anyone to convert. We just preach the acts of Christ. It’s only through our preaching that people are convinced, never by force, coercion or allurement.

What is the purpose of conversion?

It is very important to understand why we spread Christianity. It is in this way we realise God. People from even neighbouring states such as Assam are not allowed to enter Arunachal and need an Inner Line Permit. All this is because Arunachal is still inhabited by tribal people. They were living like animals. But when the messenger of Christ came to the state, there was a remarkable change in the living style of the people. You may ask anyone what was their lifestyle before the missionaries entered the state and what is the situation now.

Why are allegations made against the missionaries?

I don’t know why people of other faith are blaming Christian missionaries. But we know that those who are making false charges are not good. See what Mother Teresa has done for mankind and how Graham Staines was murdered by fundamentalists. We believe God is peace. Those who are blaming us are creating disharmony.

What are ‘healing crusades’?

Healing crusades are for physical and spiritual healing. They save people from demonic influence and curses. Its purpose is healing and deliverance.

By claiming healing via prayer, aren’t you denying medical science?

Doctors believe in science and tests and chemicals and examinations. When science fails, faith helps. It is not possible to cure every ailment with medical science. It is at this point that we call upon God and ask people to surrender totally.

Sangh Parivar is fully with the tribals: Sandeep Kavishwar

Excerpts from an interview with Sandeep Kavishwar, R S S pracharak and joint organising secretary, Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram, NE

What is the organisation doing in the Northeast for the last 40 years?

Talom Rukbo officially started the indigenous faith movement. The Sangh Parivar has been giving logistic and moral support to existing movements. In regions that did not have any such movements, we have motivated others to make a start.

Do tribals accept the Sangh Parivar?

Earlier there was mistrust. Now, they know that the Sangh is fully with them.

How many prayer halls are there affiliated to indigenous faith movements?

Some 450 prayer houses have been built over 40 years in the state in contrast to thousands of churches in the state.

How would you describe the missionaries work?

It is a national threat, hence a national issue must be made to of it. When the public pressure will increase, automatically it will become an issue.

You allege that missionary work is carried out by allurement and forceful conversion.

Numerous such incidents and proof exist that have been published over a period of time.

But the missionaries say they are just helping people. What is wrong with that?

We do not believe in talkingnegative about these people. Positive aspects of our movement will have to be highlighted. Indigenous faith movement will have to be taken forward. People can be brought together through prayers. This way, they will get organised and get united.

MS Golwalkar wrote in Bunch of Thoughts that soon Northeast will comepadristan.

We are following the constructive way. I am sure people will dodharm ka paalan. This may take time but changes will surely happen.

Will the Sangh ask for minority status to Hindus?

No, for small gains the Sangh does not believe in giving Hindus the minority status.

How strong is the Sangh cadre in Arunachal?

Full-time pracharaks are only 10 -12 but local workers should number around 10,000.

Is R S S taking the help of the government?

We only give impetus to samaj ka jaagran (mass awareness). Our focus is in creating awareness in all pockets of the society.