Antiques, antiquities, artefacts stolen from India

(→Theft of antiquities) |

(→Antiques stolen, state-wise) |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

[https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/bangalore/karnataka-has-most-number-of-stolen-artefacts/article26528757.ece Sathish G.T., 30 whisked away from ASI sites, reveals written answer in Lok Sabha, March 14, 2019: ''The Hindu''] | [https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/bangalore/karnataka-has-most-number-of-stolen-artefacts/article26528757.ece Sathish G.T., 30 whisked away from ASI sites, reveals written answer in Lok Sabha, March 14, 2019: ''The Hindu''] | ||

| − | [[File: Antiques stolen in Karnataka, 2013-18.jpg|Antiques stolen in Karnataka, 2013-18 <br/> From: |frame|500px]] | + | [[File: Antiques stolen in Karnataka, 2013-18.jpg|Antiques stolen in Karnataka, 2013-18 <br/> From: [https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/bangalore/karnataka-has-most-number-of-stolen-artefacts/article26528757.ece Sathish G.T., 30 whisked away from ASI sites, reveals written answer in Lok Sabha, March 14, 2019: ''The Hindu'']|frame|500px]] |

At least 12 idols have been stolen from protected monuments in Karnataka in the past six years, and none of them has been recovered by the police. | At least 12 idols have been stolen from protected monuments in Karnataka in the past six years, and none of them has been recovered by the police. | ||

Revision as of 11:11, 14 March 2019

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

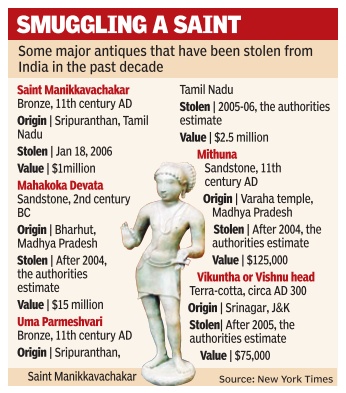

Theft of antiquities

The Times of India, Aug 16 2015

Amulya Gopalakrishnan

Will reworking the Antiquities Act stamp out the illicit trade in cultural artefacts? Sunday Times examines both sides of the debate What is anantiquity? Itcould be an idol in a shrine, a piece of jewellery passed on from your grandmother, or a casually bought souvenir that is much older than you realize. These are all covered under the Antiquities Act of 1972, but the ethics of owning and circulating them are not the same. Despite a stringent law, antiquities continually stream out of India. Their owners secretly sell them abroad, flouting export restrictions. The ongoing Chennai trial of Manhattan-based art dealer Subhash Kapoor, reveals how antiquities are spirited across the border by a network of smugglers and dealers, sold to museums, galleries and collectors.

Recently, Union culture minister Mahesh Sharma told Parliament about the theft of eight antiquities in the last year. As a remedy , he has spoken of liberalizing the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972, to create a more open market in India that might deter smuggling.

While the details are still being worked out, it is expected to involve a measure of selfcertification, electronic registration, and easier internal trade in antiquities. “We have invited comments, and will amend the law very soon,“ said Rakesh Tiwari, director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Flaw in the law?

The antiquities law covers objects over a 100 years old, forbids their export by citizens, and allows them to be sold within India only with a licence. Owners of an antique item must register it with the ASI. The state can also compulsorily acquire an object from its owners, without any reliable valuation of a fair price.

According to art historian Naman Ahuja, its chief flaw is the broad and meaningless definition of antiquities. A Chola bronze of inestimable historical value is treated the same way as a flea market idol that just happens to be a hundred years old, and may be personally valuable to a col ector, but is not worth the government's attention. “The state cannot possibly defend so much material; the law's only use is to harass middleclass citizens,“ he says. “What s the need for this elaborate registration, treating us like children?“ says Dadiba Pundole of the Pundole Art Gal ery that acquired a licence to sell in 2011.

And despite the punitive strength of the law, it hasn't been able to stem the illicit low of antiquities out of India. “That only one Subhash Kapoor has been caught in so many years only shows how neffective the law has been,“ says Ahuja.

In his view, this repressive legal regime has discouraged Indians from buying and selling antiques, recognizing special pieces, producing scholarship and images. A thriving internal market, he says, would be the best safeguard against smuggling.

“Without an open market, nobody knows where things are, and fakes circulate with ease,“ says art historian Kavita Singh. In her view, this law speaks of the anxiety of a decolonized nation, and the political situation of the 1970s, where the government and erstwhile royal families who held large art collections were suspicious of each other.

She points to laws in the UK and Canada that balance the owners' right to their property and the nation's investment in important cultural objects -you can place your object for sale in the international market, and the state is given time to match the highest bid.

Can selling within India discourage smuggling? Opinion is divided. Singaporebased S Vijay Kumar, a heritage enthusiast who runs the website Poetry in Stone, disagrees with Ahuja and fears that any dilution in the law would give a free run to underhand dealers, given the more lucrative market abroad. “We have a handful of corporate buyers in India, who can't compete with the billionaires and museums of the West,“ he says. ASI officials also privately say that this loosening of the law will only benefit wealthy lobbies.

Kirit Mankodi, an archaeology professor who posts information and photographs about stolen antiquities on his website, Plundered Past, says that India's real problem is the inability to prove provenance.Photographs and dated documents are essential to tell a looted object apart from a legitimately owned one. And yet, “there is no public register to report losses, or for buyers to check out an object,“ he says. The National Mission for Monuments and Antiquities was set up in 2007 with a fiveyear plan to create an exhaustive database, say ASI officials.In 2015, it remains far away from the goal.

Whose patrimony is it?

While there is growing consciousness about looted antiquities, there is also a charged debate over whether nations are right to be so possessive about their heritage.Many source nations demand repatriation of objects taken away long ago -whether Greece's Elgin marbles, Egypt's Rosetta Stone or India's Koh-i-Noor diamond.

Some in the museum world, like Getty Trust president and provocateur James Cuno, disagree with these “nationalist-retentionist“ arguments, arguing that the great cosmopolitan museums (that happen to be in the West) are better equipped to preserve and display previous antiquities to the world, whose collective heritage they are.Others say that national cultures are complicated affairs, made by chance encounters and unforeseen circumstances, and that there must be a cut-off point to correcting historical wrongs.

“But as things are, for some of these global museums to display our antiquities, Indian laws may have been broken, violence committed on the monument, a sculpture wrenched from its niche, the context destroyed. When the sculpture was exported, Indian laws were broken again,“ says Mankodi.

Singh points out that it's often the museums still on the make -in Australia, Singapore and other locations -that are fed by the illicit supply of antiquities, and have had to return several artefacts bought at a high price. A much better strategy for India, says Singh, would be for Indian museums to capitalize on their vast stores, and loan pieces to museums in other nations.

As the antiquities law is now reconsidered, perhaps the answer would be to work with the world, not against it.

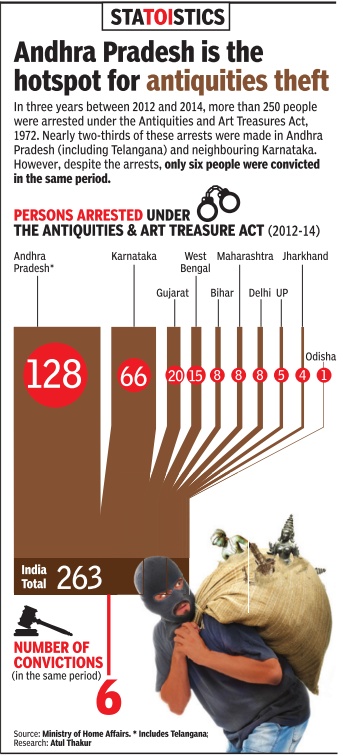

Antiques stolen, state-wise

Karnataka

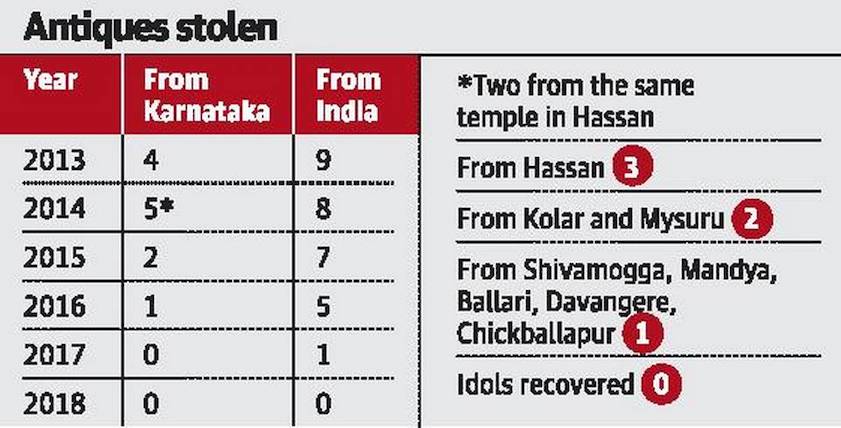

2013-18/ Antiques stolen in Karnataka

From: Sathish G.T., 30 whisked away from ASI sites, reveals written answer in Lok Sabha, March 14, 2019: The Hindu

At least 12 idols have been stolen from protected monuments in Karnataka in the past six years, and none of them has been recovered by the police.

Karnataka tops the list in the country that has seen 30 idols or artefacts being stolen from Archaeology Survey of India (ASI) sites, reveals the Ministry of Culture in a written answer to a Lok Sabha question last week.

In a span of three years, a stone Nandi and a stone Ganesha were stolen from the Ramalingaswara temple complex at Avani in Kolar district.

A stone Shivalinga was stolen from a Shiva temple in Thimalapura in Ballari district; while, the eight-armed goddess Mahishamardini was stolen from the Panchalingeswara Temple in Mandya is yet to be recovered.

Tracing problem

“The demand for these Hoysala and Chalukya idols exist and the three southern States are susceptible as there are hundreds of unprotected or State-protected sites,” said T. Arun Raj, Superintending Archaeologist (Museum), ASI, New Delhi, and who was in-charge of Karnataka till recently.

In Hassan district, three sculptures of Hoysala period were stolen.

A seated Chaturbhuja Ganesha sculpture from Bucheshwara Temple at Koravangala near Hassan was stolen on the night of October 11, 2013.

ASI officers had filed the complaint with Dudda Police in Hassan taluk.

Within a year, two schist stone sculptures were stolen from Nageshwara Temple at Mosale in Hassan taluk.

A case was filed at Gorur Police Station. “In both the cases, the police have reported that the stolen sculptures were not traceable (C-report). I recently visited both the police stations and spoke to the officers concerned. They have not been able to trace them so far,” said L.B. Kamath, Junior Conservation Assistant of ASI posted in Hassan.

Lack of sufficient staff to guard the monuments is said to be one of the reasons for the thefts. H.N. Nagaraj, district general secretary of Temporary Workers Union of ASI, said the sculptures were stolen from a place that had no night watchmen.

2014

Recovery of artefacts from Australia

The Indian Express, October 11, 2015

During his visit to India in 2014, the then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott had handed over to his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi two antique statues of Hindu deities which had been stolen from temples in Tamil Nadu before being bought by art galleries in Australia. Abbott returned the idols, one of which was a Nataraja –the dancing Shiva– belonging to the Chola period 11th-12th century. The other was Ardhanariswara dating to 10th century. Ardhnariswara, the androgynous form of Shiva and his consort Parvati, is depicted as half male and half female, split down the middle.

The Nataraja statue, cast in bronze, was purchased by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in February 2008 from Subhash Kapoor who was then based in New York.

In 2012,Subhash Kapoor, owner of the “Art of the Past” gallery in New York, was arrested in Germany and subsequently extradited to India. He has been accused of conspiracy to commit burglary and smuggling from Tamil Nadu of antique idols of Hindu deities belonging to Chola dynasty. German Chancellor Angela Merkel had on October 6 handed over to Prime Minister Narendra Modi a 10th century Durga idol which had gone missing from a temple in Kashmir over two decades back and was later found in a museum in that country.

2016

June 2016: Recovery of artefacts from the US

The Hindu, September 24, 2016

In June 2016, the United States formally returned to India about 200 stolen cultural objects, which include 2,000-year-old artefacts, part of a $100 million trove unearthed by an investigation of Subhash Kapoor’s art business. What emerges from these long battles to reclaim articles that constitute cultural heritage is the insight that a dedicated national agency with State government support would be better equipped to fight the scourge of theft and illicit transfer. With trained personnel, it could devote itself to the task of documenting antiquities and ensuring that the country’s ports are sealed against smuggling.

India Pride Project (IPP)

The Times of India, June 12, 2016

Debayan Tewari

Chasing Ganeshas: Meet the art sleuths bringing India's stolen heritage home When Prime Minister Narendra Modi re turned from his foreign travels, in his luggage was a consignment of 200 antiquities, including a beautiful 1,000-year-old Ganesha bronze, that the US government handed over to him. What few know that is behind the goodwill gestures and photo-ops highlighting cultural cooperation is a group of very committed idol chasers who helped investigative agencies in the US crack the cases of stolen antiquities. In March, when special agents in the US seized two stolen Indian artefacts -a sandstone stele of Rishabhanata and a panel with Revanta and his entourage -from an auction in New York as part of the ongoing decade-long Operation Hidden Idol, among the first to identify the 10th century Rishabhanata was Vijay Kumar, an accountant working for a shipping company in Singapore.

Kumar has been photographing and documenting Indian antiquities for the past 12 years, trying -in his own way -to prevent their theft and ensure the return of stolen artefacts to India.In 2014, he and fellow heritage lover and art enthusiast Anuraag Saxena began the India Pride Project (IPP) to “restore the nation's pride through restoring its culture“.

IPP began with 20 members and has since grown to 4,000, including researchers, art-loversturned-private-investigators, bloggers, freelance photographers and journalists. It is managed by a core team of 40 people.

Except for Kumar and Sax ena, the rest have chosen to stay anonymous, providing expertise and inside information to the group. “Our members are heritage enthusiasts, scholars, archaeologists... many help but want to keep their identity private,“ says Kumar, who grew up in Chennai and was drawn to heritage conservation after reading `Ponniyin Selvan', a Tamil historical novel based in the Chola period. “My whole sense of cultural pride comes from the book,“ he says.

IPP helps track and restore stolen artefacts by contradicting the provenance that museums are provided by not-so-legitimate art dealers. Volunteers use photographs of the artefact in its original site from the IPP database or from archives to prove that it was stolen. For example, in the case of a Nataraja idol that Australia returned to India in September 2014, IPP volunteers matched photographs taken by the French Institute Pondicherry (IFP) in November 1994, frameby-frame, to prove that the idol on display at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) was stolen from Sripuranthan in Tamil Nadu.

Saxena, a banker-turned-education executive who is also based in Singapore, says IPP depends on a network of volunteers. “We are spread across the world and are from various background and professions. It is very normal for a volunteer who is a CEO in Singapore to work with another who runs a cloth-shop in a small village in Tamil Nadu,“ he says.

IPP also scans catalogues of art galleries to track down looted antiquities. Kumar used a print cata logue from in ternational art thief Subhash Kapoor's Art of the Past gallery to match a stat ue of Uma Parameshwari in Singapore's Asian Civilizations Museum with a photograph of a stolen idol from Ariyalur that the Tamil Nadu police's idol wing released.

It's a long, slow process to prove that the idols were stolen and then get them back. The latest seizures in New York came after three years of work, while proving that the Uma Parameshwari statue was the same one stolen from Ariyalur took five years with valuable time being lost mostly due to red tape in India, explains Kumar.

Kumar began photographing temple architecture and idols in Tamil Nadu as a hobby . These photographs have become a part of the database IPP volunteers are building to compensate for the lack of an official database. “We do documenting missions twice a year for two weeks,“ he says.

Besides field work, IPP also uses social media, encouraging members and volunteers to contribute photos to its archive.

After the arrest of Kapoor and his deportation to India in 2012, Kumar reached out to Jason Felch, an investigative journalist based in the US, who published a story about objects smuggled by Kapoor on display at NGA. “Vijay immediately began supplying me with detailed information about other objects in the NGA's collection and possible links to objects stolen from Indian temples,“ Felch told TOI in an email interview. “Soon, we developed a collaborative relationship with journalists in Australia and India, each of us working our sources and sharing information to advance the story .“

While Kumar leads research and analysis, Saxena handles coordination with government agencies and the media.

But Saxena does not want IPP to be seen as police informers.“People are interested in the whodunit stuff, and we are often seen as khabris (informers). But our work is more than that,“ he says.

IPP's website has detailed information about how it helped to identify the Sripuranthan Nataraja, Vriddhachalam Shiva Ardhanari and sandstone Yakshi seized from Kapoor's warehouse in the US, a bronze Ganesha in Toledo Museum, and the Uma Parameshwari statue in Singapore. Vijay says they are currently tracking more 4,000 antiquities.

It's work that has gained them the respect of enforcement agencies around the world. US Homeland Security Investigations special agent Brenton Easter told TOI: “They have been helpful as have other academics and institutions, like the French Institute of Pondicherry . Without the record keeping and image recognitions done by these individuals and entities many of our recoveries would take much longer.“

September 2016: Recovery of artefacts from Australia

The Hindu, September 24, 2016

The return to India of three ancient sculptures from the National Gallery of Australia is another milestone in the long and difficult campaign waged by several countries to repossess their cultural treasures, which have often been bought by museums from idol smugglers. As the provenance of the artefacts — the 900-year old statues of Goddess Pratyangira and Seated Buddha, and the third century Worshippers of Buddha — became clear, the only ethical course open to the Australian gallery was to restore the sculptures, which it must be commended for pursuing. Evidently, the two icons other than the sandstone Seated Buddha were acquired from a New York-based art dealer, Subhash Kapoor, for about $840,000 on the strength of fake documentation.

The National Gallery of Australia’s inquiry into the status of its Asian art objects conducted by a retired judge, Susan Crennan, has had the positive outcome of identifying 22 articles that have questionable or doubtful credentials, 14 of which were purchased from Kapoor. Many of the findings in the Australian review underscore the importance of creating a strong repository of information of all Indian antiquities, backed up by unimpeachable forensic records, so that they may be claimed without difficulty at a future date. A lot of the illicit trade has been carried out by smugglers who have laundered the provenance of idols using fake documentation designed to overcome the prohibition imposed by the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972 on non-governmental exports. Providentially, it is the records of a research institution such as the French Institute of Pondicherry that helped establish the claim to the 11th-12th century Nataraja idol stolen from Tamil Nadu in 2006. Documentation of antiquities using public and private records should become a national mission. These treasures could then be put on display in national museums.