Anna Molka Ahmed

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Anna Molka Ahmed

April 29, 2007

EXCERPTS: Different strokes

A book on the life and works of Anna Molka Ahmed.

Marjorie Husain writes about Anna Molka Ahmed’s early days in Lahore.

On her first day at the university, Sheikh Ahmed escorted Anna up to the gate; the date was June 1, 1940, a historic occasion. Anna Molka took a deep breath, marched in through the gate and later recorded her initial impressions. “I entered the university gate, shaded at that time by one of the oldest and most beautiful peepal trees in Lahore. The university was old — it had been established in 1862, and expanded into a university in 1882 — but the tree was older, and stood proudly in front of the gate greeting visitors, it was a natural division for coming and going.” …

The vice-chancellor of the University Mian Afzal Hussain welcomed Anna and explained that he had started the new department despite considerable opposition and was depending on her to make a success of it. Anna discovered to her consternation that there were no rooms allotted for the department, furniture would have to be designed and made, and most disturbing, there was as yet no equipment. It was a department without books or slides, and a syllabus would have to be evolved from scratch. Further shocks were in store as she was informed that the subject had been introduced for girls only, to keep them from overcrowding or even joining classes of subjects suitable for men.

To her surprise, she learnt that a university syndicate composed of learned judges, professors, doctors and scholars, variously of Indian, American and European origin, had in their collective wisdom decided that valuable university space and resources were being wasted on women students, as the only profession they were fit for was marriage. However, as more and more emphasis was being placed on the emancipation of women, they should not be stopped but rather ‘side tracked’. After all, the consensus was that art as a subject was useful only for keeping women occupied and turning them into housewives properly equipped to adorn themselves and decorate their homes.

Hearing this, Anna Molka became incoherent with the outrage she felt both as a woman and as an artist, and over three decades later was still incensed. Alarmed at her indignation, Mian Sahib rang for his peon and told him to bring a glass of cold water to cool her down. Through the years, many more glasses of cold water were to be sent for when he was unable to increase grants or necessary budgets, or could not accede to her repeated requests for more space. …

While preparations were underway, Anna Molka was asked by the vice chancellor to visit the local women’s colleges to lecture on subjects such as, ‘What is art’, and ‘The value of art in daily life’. He explained that these lectures would be an excellent introduction to art as a useful subject for study. Then, with the permission of their parents and cooperation of their college principals, the students could switch their subjects choosing art as one of their electives ...

The Lahore Government College for Women had an English principal, a Miss Geary, who was very much in favour of the new developments at the university. She felt that the art and music subjects would help the girls culturally and artistically in their homes as well as equip them to follow careers as teachers if they so chose. Most of the students who joined Anna Molka’s art classes came from this college, an eclectic mix of young Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Sikh women. The Hindu College and the Sikh Fateh Chand College wanted to send all their first year Intermediate students for art and music classes, so that all they would only have to teach them in their own colleges would be English and one other subject. At this stage however, it was not practicable for Anna Molka to take on a hundred students when she was the sole teacher.

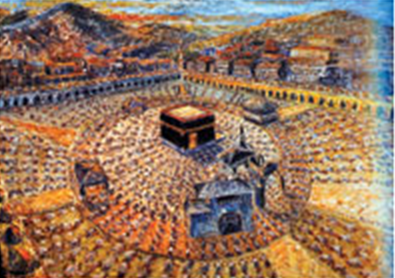

The fourth college Anna Molka visited was the Islamia College for Women. There she lectured the students and their teachers on the great heritage of Muslim art. The staff and students were extremely enthusiastic, and she left the college feeling very optimistic. Soon after she arrived back at the university, 30 burqa-clad students descended on the department in tongas. They were so keen to join her classes, they had left their college without permission from the principal and without even discussing the matter with their parents. Very regretfully Anna Molka had to send them back and sadly they were never accorded the necessary permission from the Anjuman of their college ...

Anna started off with a class of 23 girls. From the very first day, Anna Molka’s commitment and personal interest in her students was obvious to all. Anna devised a programme of art teaching, starting the classes with theory, practice and history. In class, Anna Molka found her students inhibited, some of them drawing like six-year-olds, though they were already matriculates but they persevered, worked hard and began to do well in design. Their rich sense of colour delighted her and she attributed this phenomenon to their indigenous cultural roots. Anna sometimes found it hard to maintain the discipline she felt was owed to art study. She stopped the girls from knitting in the class during lectures on art history, but realising she could not stop them from snacking on dry fruits and nuts, joined in with them. “We all threw the shells in one corner of the room and chewed through prehistoric art with much greater interest and gusto.” …

Once Anna became ill with malaria and was lying prostrate on her bed when representatives of her class burst in, absolutely distraught. They begged her to come to the class, fearing that without the teacher present, the department would be closed down. Anna was unable even to stand upright, but as she was very slim in those days. The girls carried her to their car and then upstairs to the classroom. There they arranged her comfortably with cushions on the model platform and continued with their work, drawing painting and designing. They filled in their own attendance register, supervised the locking up of the department and delivered her home after class ...

Anna delivered a series of radio lectures and wrote numerous newspaper articles focusing on creativity and the intention of the artist; modern methods of art teaching; and other art education-related matters. It was a challenging, busy, but overall happy time for Anna Molka and Sheikh Ahmed. Money was always short but their affection for each other remained strong.

Excerpted with permission from The Sun Blazes the Colours Through My Window: Anna Molka Ahmed By Marjorie Husain Research and Publication Centre, National College of Arts, in collaboration with Ferozsons. 60 Shahrah-i-Quaid-i-Azam, Lahore Tel: (042) 630 1196-8 UAN 111-62-62-62 ISBN 969-8623-18-3 236pp. Rs1,800

Marjorie Husain, an authority on the art history of Pakistan, is an art critic and curator of a number of exhibitions. Her other books include Bashir Mirza: The Last of the Bohemians and Ali Imam: Man of the Arts.