Amul (Anand Milk Federation Union Limited)

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

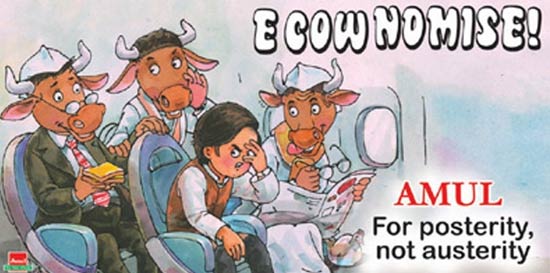

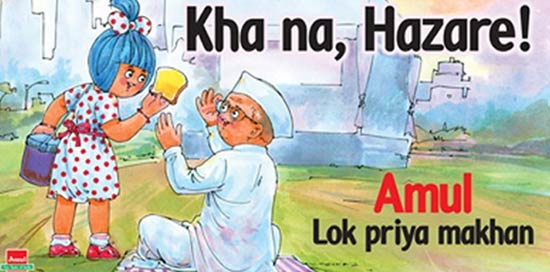

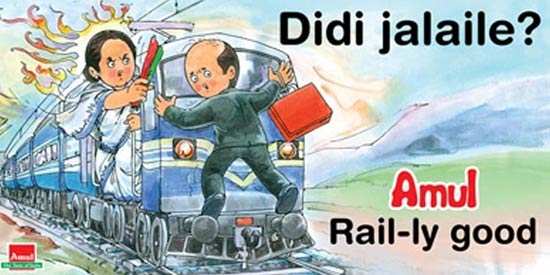

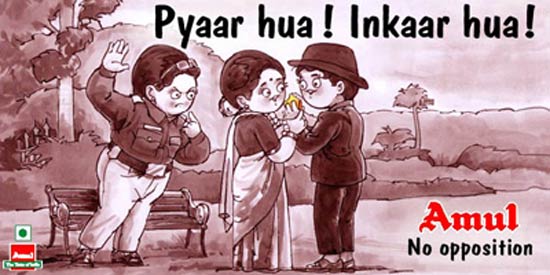

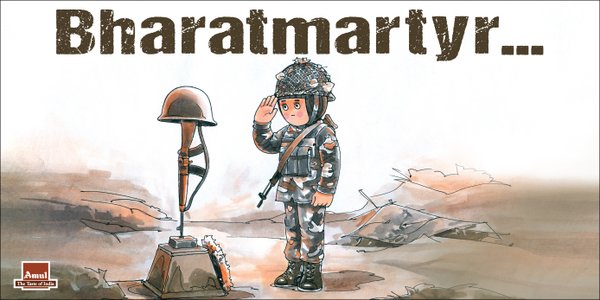

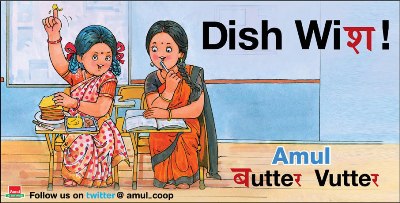

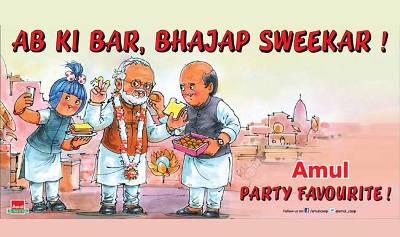

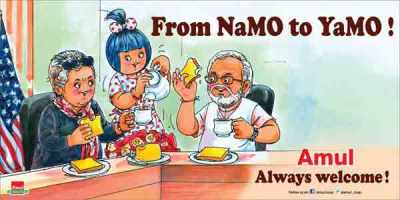

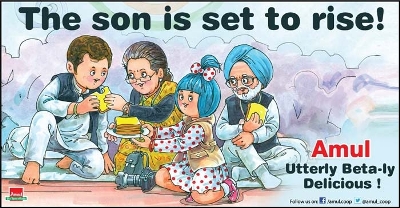

[[File: Amul ad28.jpg| Amul spoofs Politics|frame|500px]] | [[File: Amul ad28.jpg| Amul spoofs Politics|frame|500px]] | ||

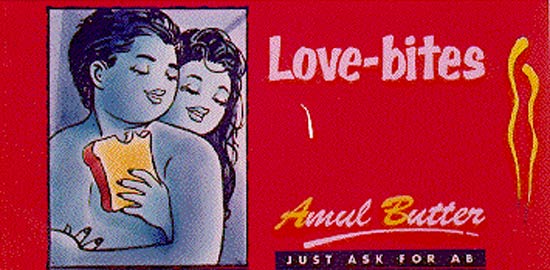

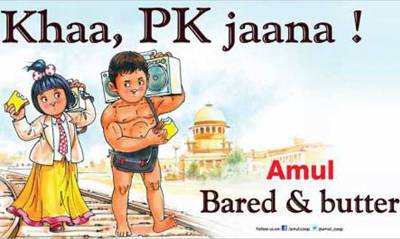

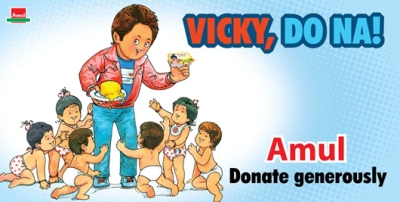

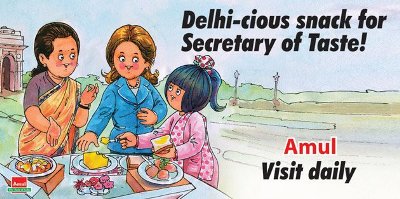

[[File: Amul ad29.jpg| Amul spoofs Filmistan|frame|500px]] | [[File: Amul ad29.jpg| Amul spoofs Filmistan|frame|500px]] | ||

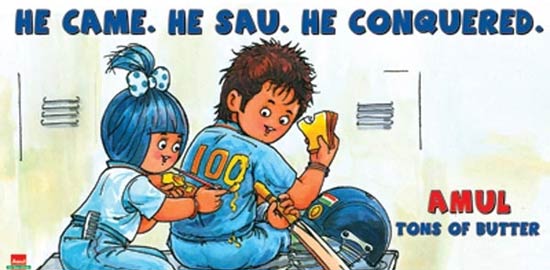

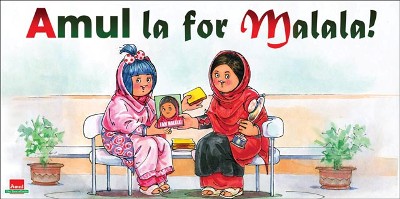

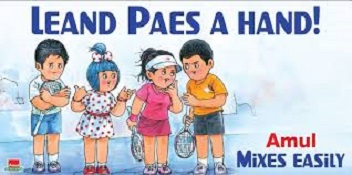

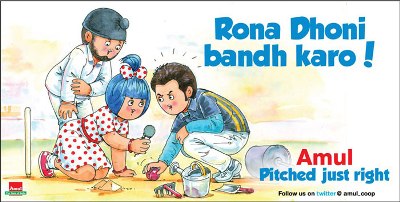

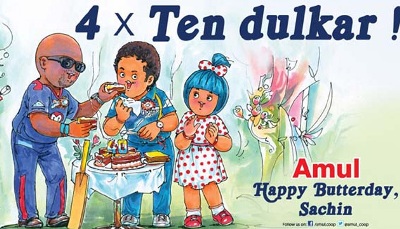

| − | [[File: Amul ad30a.jpg| Amul on | + | [[File: Amul ad30a.jpg| Amul on sports|frame|500px]] |

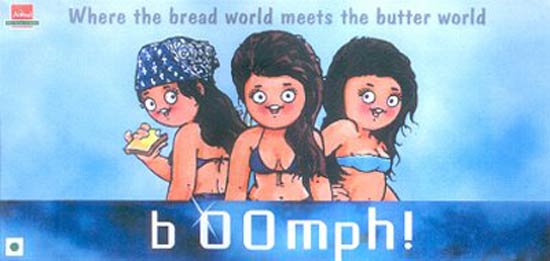

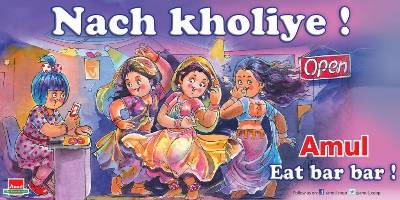

[[File: Amul ad31.jpg| Amul on Mumbai’s dance bars: okayed by the Supreme Court but the state government drags its feet|frame|500px]] | [[File: Amul ad31.jpg| Amul on Mumbai’s dance bars: okayed by the Supreme Court but the state government drags its feet|frame|500px]] | ||

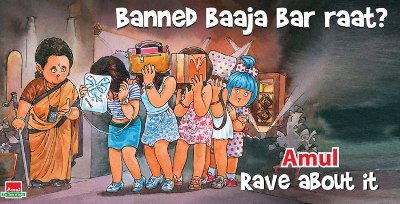

[[File: Amul ad32.jpg| Amul on a high profile raid on a rave party|frame|500px]] | [[File: Amul ad32.jpg| Amul on a high profile raid on a rave party|frame|500px]] | ||

Revision as of 19:56, 6 November 2016

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Contents |

Amul in the 21st century

Amul 2.0: What the ongoing change means for the Rs 18,143 crore cooperative [1] By Naren Karunakaran, ET Bureau | 31 Jul, 2014

In 2014 around 85% of Amul’s membership still comprises small and marginal farmers. For the new emerging lot dairying is a hard-nosed business. Around 85% of Amul’s membership still comprises small and marginal farmers. For the new emerging lot dairying is a hard-nosed business.

Several decades after Amul was established that movement, better known to the world as Amul, is facing yet another churn, a slow and silent one. Its farmer membership of 3.3 million -- the very composition of its bulwark, its raison d'etre - is undergoing a makeover. The upstream of the Amul value chain is changing like never before.

In the 21st century there has been a steady, methodical infusion of large, affluent farmers into the supply ecosystem. They seek to establish dairying units on a commercial level, with a big herd size of 30-50 animals and all the trappings of a modern dairy, complete with automated systems and Swedish milking machines.

They rub shoulders with the typical Gujarati village dairywoman engaged in subsistence or supplementary-income sort of dairying. They rub shoulders even with the likes of the landless such as Shantaben of Jalotra village in Banaskantha who secures green fodder for her cows in lieu of her labour in the fields.

Amul 2.0: What the ongoing change means for the Rs 18,143 crore cooperative: Around 85% of Amul's membership still comprises small and marginal farmers. For the new emerging lot, imbued with the keen Gujarati ken for profits, dairying is not a livelihood plank. It is hard-nosed business.

Those at the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) --owner of the Amul brand and the apex body of the milk unions -- are encouraging the transition. "We already have over 5,000 such large commercial farms," reveals RS Sodhi, managing director of GCMMF. "And they will only grow in numbers." These large farms, quite under the radar for the casual observer, suddenly seem critical for the future growth of GCMMF, even as it reorients itself, and begins to address and design specific programmes for these relatively new entities.

Compulsion To Grow This lot is expected to play a singular role in fuelling milk supplies as GCMMF begins to cope with a growing population, higher incomes, increasing health consciousness, and the consequent explosion in demand for pouch milk and value-added products across the country.

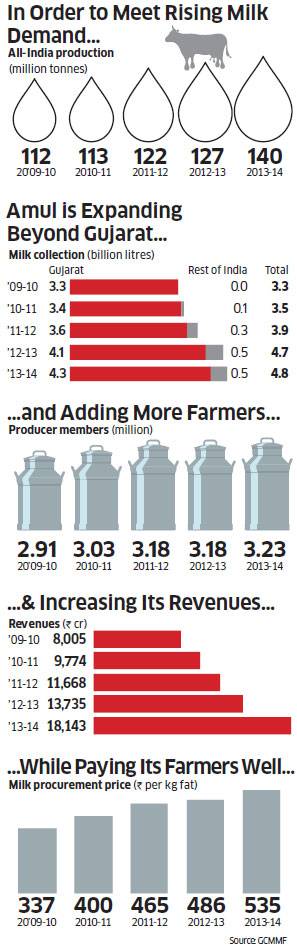

Estimates by the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) indicate milk demand is expected to rise to 180 million tonnes by 2022 (around 140 million tonnes in 2014). In order to meet this demand, an average annual increase exceeding 5 million tonnes over the coming years is required.

Planning, not only for the near, but the distant future, is key to sustenance, estimates the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union, popularly known as Amul Dairy, and the oldest of the 17 district unions. "All along our focus has been on products, and processing infrastructure." The downstream of the value chain prevailed.

For a long time, Amul was faced with a situation where its milk procurement was increasing at a much faster pace than it could dispose in the form of value-added products. It was therefore forced into a milk powder play, which it didn't relish.

2010-14: new markets and sourcing milk locally

It was only when GCMMF started entering new markets for liquid milk – Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, around 2010 -- the realisation dawned that hauling milk all over the country from Gujarat wasn't a prudent idea. In any case, milk from Gujarat wasn't enough for its expansion. Even today, two special milk trains leave Banaskantha for Kanpur every alternate day. From an era of milk plenitude, the tide turned, forcing GCMMF to seriously explore sourcing milk locally in UP and elsewhere. "We were falling short by 10% or so then," says Sodhi. The Amul pattern of coop structure is now being transplanted in UP.

The supply situation has eased, but the strain to keep pace with spiralling demand, and the windfall accruing from the changed circumstances, are showing. GCMMF posted a turnover of Rs 18,143 crore in 2013-14, along with its highest-ever growth of 32.1%. Over the last six years, GCMMF has recorded a compounded annual growth of 23% and hopes to touch Rs 30,000 crore by 2020.

The induction of a force multiplier in milk supplies -- like the professionally run commercial farms, or 'tabelas', as villagers in Anand, the home of Amul Dairy, describe them -- was in a way inevitable. Nowhere is this scorching growth more apparent than at the Banaskantha District Coop Milk Producers Union, or Banas Dairy as it is called.

With a daily milk collection of over 3.5 million litres, it is the largest dairy in Asia. Banas Dairy relies a great deal on large farms. They already account for 20%, or 700,000 litres, of milk procured every day. Abdul Rashid of Semodra village and Punmabhai Desai from Bevata village are exemplars of the new tribe (See box: The New Amul Farmer)

Why is commercial dairying attractive in Banas/ Gujarat?

Lure Of The Dairy

Why is commercial dairying attractive in Gujarat? Selling any quantity of milk is not an issue with the Amul ecosystem in place. The price on offer is good. Banas Dairy offers Rs 590 per kg fat, perhaps the best price for milk anywhere in the country. GCMMF officials insist it may be the best in the world if subsidies for milk in foreign countries are pared out.

In addition to a good price, access to cheap cattle-feed, vet services and support for buying milking machines, members of the cooperative are also eligible for a share of the 'price difference', or profits, which can be substantial. For 2013-14, Banas Dairy announced a rate of 14%: a farmer receives Rs 14 for every Rs 100 worth of milk supplied during the year. On July 16, the Banas Dairy disbursed Rs 430 crore. That's not all. The village coop societies also disbursed -- another Rs 200 crore -- to its member farmers. Last year, Rashid earned Rs 3.5 lakh as price difference alone.

While the pickings seem good, these commercial dairies, as all other farmers, also retain a degree of freedom to do whatever they like with their milk as long as the mandatory minimum is poured at the village society. This is around 400 litres per cow per year to retain voting rights; and 750 litres to be a managing committee member. The situation is pregnant with possibilities

Farmer-consumer balance

The sheet-anchor of the Amul pattern has always been maximising of benefit to farmers and providing low-cost, value-for-money products to consumers. The tradition continues. "If you pay a good price, milk will come," says Sodhi. Subsistence farmers never bothered about costs, inputs, outputs or efficiency. "We are now fostering a business model," he says, and insists that the future of Indian dairying lies in encouraging "self-managed, farmer-managed units of 40 animals or so", and not the promotion of large private dairying behemoths of 5,000-plus animals.

Only now, Sodhi is a trifle worried about the farmer-consumer balance. With a cost-conscious, profit-seeking professional flock under his wings, he will now have to be more mindful about inflationary trends, input costs in dairying, and perhaps calibrate milk prices at the consumer end in a more nuanced and acceptable manner.

The Punjab milk crisis of just two years ago is still on everyone's mind. Commercial dairy farmers took to the streets as rising input costs made their units unviable. Many downed shutters.

The farmer-consumer conflict, therefore, is only going to get more complex for GCMMF in the future. Sodhi wonders why urban consumers raise hell with an increase of a couple of rupees in liquid milk prices when they don't mind splurging on fast food, fancy electronic gadgetry or mobile air time. However, for now, things aren't choppy.

Influx of large Farmers

Advantage, Large Farmers

"Big farmers will bring in 50% of Banas Dairy's milk in 10 years," proclaims Parthibhai Bhatol, chairman of Banas Dairy, who was elected chairman of GCMMF after the visionary Verghese Kurien demitted office. Bhatol, the dairy veteran who has steered Banas Dairy to its prima donna position today, is certain that a business approach to dairying is the only way to go if the Amul coops have to attract and retain the interest of Gujarat's rural households and the restive youth in dairying.

He has little choice. Many dairying families are dropping out of the system for varied reasons. Membership has reached saturation. "No one has been left behind, even the landless who tie their animals on the roadside are members in Banaskantha," he says.

Will this influx of affluence unsettle the cooperative spirit and dilute Amul values? GCMMF officials don't see that happening and underscore the cooperative dictum of 'one member, one vote', hinting that a tilt in balance, in favour or against a section of farmers, is not possible. "With commercial farms, efficiencies will only increase; productivity will rise," says Kishore Jhala, chief general manager of GCMMF. India's productivity per animal is abysmally low; about 987 kg per lactation as against the global average of 2,038 kg per lactation.

Moreover, they fit into the federation's future plans. In situations where a controlled environment is necessary -- for instance, innovating with neutraceuticals (food products that provide both health and medical benefits -- these modern, high-tech farms would be ideal locations.

Stigma on cattle breeding

Bhatol believes that it was imperative for them to move along this path as the present generation in dairying families is showing signs of restlessness. Girls also do not prefer marrying into families that keep animals. Even the boys, better educated and more aware than their forebears, are gravitating towards jobs in cities. Even call-centre jobs are enticing.

"There is no life in dairying," says Haresh Chaudhury, 30. "All our waking hours, which starts at 4 am, is spent feeding, milking, caring and tending to animals." He kept a herd of 10 for several years, but slowly became embittered by the sheer drudgery of it all.

One day, he sold all his animals for a song and breathed freedom. "Now, we have many career options, unlike our parents," he says. Growing cash crops doesn't call for the same labour intensity as dairying. Chaudhury has tried his hand at growing papayas. That continues. He is now examining options in real estate and retailing. Bhatol says a churn -- arising from a mix of rising aspirations, and dairying economics at the grassroots -- is inevitable and that farmers will enter and leave the system. It's evolutionary. Abdul Rashid is more direct. "All these three to five animal types will eventually wither away," he says, with a sage-like shake of his head.

Beyond Gujarat

What do all these structural churns, heightened political activity and acrimonious interference, within and outside cooperative boardrooms, as witnessed in recent years, and the absence of a charismatic leader like Verghese Kurien who held the family together, mean for the future of Amul?

As the first GCMMF chairman post the Kurien era, Bhatol has been in the thick of the messy and disquieting transition. He says Amul values revolve around providing maximum benefit to farmers. If this is adhered to in all earnest, he adds, the rest can be handled.

Bhatol describes how his recent intervention in UP is benefiting a whole new lot of farmers. Exploitative private players wouldn't pay more than Rs 18-20 a litre. As expected, there was resistance to Amul's entry in the state. He ratcheted up the game and started offering Rs 28. Over 1,100 village societies have been formed. Milk collection has reached 200,000 litres a day. "This winter we will reach 500,000 litres," he says.

Amul is present across much of Gujarat. Saurashtra and Kutch, untouched all these years, is also now under the umbrella. Now, it's the turn of farmers in other regions to benefit from Amul's direct play, although in the past the Amul/Anand pattern has been replicated in many states.

NDDB, which had been created to proliferate the Anand pattern, has now begun promoting milk-producer companies, a blend of a cooperative and a private limited company, under the Companies Act. "A producer company insulates us from undue government and political interference, and is more transparent in its operations," says SK Bhalla, CEO, Maahi Milk Producer Company Limited, based in Rajkot. With 76,000 members, a collection of 600,000 litres a day, it has been fairly successful, and hopes to reach a turnover of Rs 1,000 crore in 2014-15.

Politics and politicians

The deep suspicion of politics and politicians will remain. However, they cannot be wished away. It's how a situation or a set of circumstances are managed. Bhatol reveals how the present UP chief minister, despite stiff opposition, is helping him build a chain of Amul milk-processing plants in Faridabad, Lucknow and Kanpur

Political patronage, or interference, is not new to Amul. "In fact, we are born out of politics," explains Kishore Jhala, alluding to its formative years. Only then, the politicians were more statesmen-like. And Kurien was a buffer between the political establishment and the cooperative. Today, Amul, for good or bad, is directly exposed to politics and politicians. The churn continues

Manthan (1976)

Manthan (The Churning), the 1976 Shyam Benegal film, financed by marginal farmers [i.e. by Amul], and set against the backdrop of Operation Flood, captures the agrarian tumult and the promises held out by the dairy cooperative movement in Gujarat. [The film is a hagiography of Amul founder Mr Kurien.]

The New Amul Farmer

Banas Dairy likes to describe farmers like Abdul Rashid as progressive milk producers (PMPs) and is grooming another 7,100 farmers to join the fold. His is an example worth emulating.

Rashid, with a herd of 48 cows (25 milking cows), supplies 240 litres of milk a day to the dairy. His last year's supply was worth `18 lakh and he made a neat profit of `5 lakh. "I spend `2.4 lakh on labour alone in a year," he says, mischievously hinting he could have saved this money if his family members involved themselves in tending to the herd.

Over the years, Rashid has spent over `10 lakh on infrastructure: a warehouse to store a year's stock of feed, an animal housing with fans and foggers to manage heat stress of his herd, sprinklers over six bighas of land to grow green fodder, water-recycling and composting systems. He also rears his own stock. He was the first to buy a `45,000 DeLaval milking system in the entire district in 2011.

Unlike Rashid, with years of experience, 31-year-old Punmabhai Desai from Bevata village, a commodity trader, is a newcomer to dairying. He earns around `5 lakh a year from his trading activities and another `4 lakh comes as agriculture income.

"Dairying is a safe bet," says Desai. That's why he didn't think twice before mortgaging 40% of his five-hectare land for a `45 lakh loan from ICICI Bank to set up one of the most modern dairies in his region. He own 25 milking animals. His farm is already a "must visit" for hordes of farmers from Ghodsar and adjoining areas. "Within two years I will install bulk chillers and target 1,000 litres of milk supply a day," he says

Advertising campaign

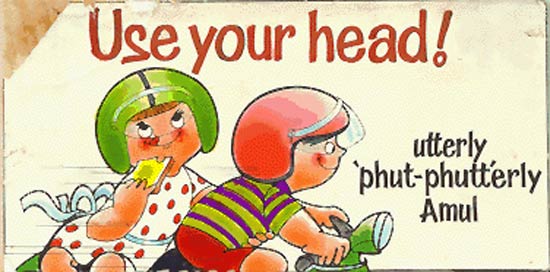

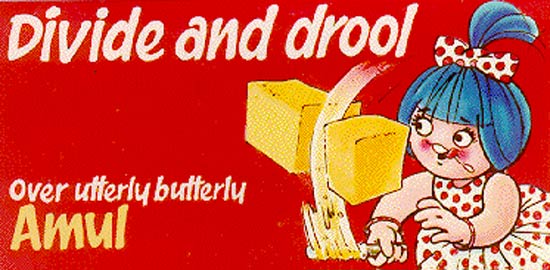

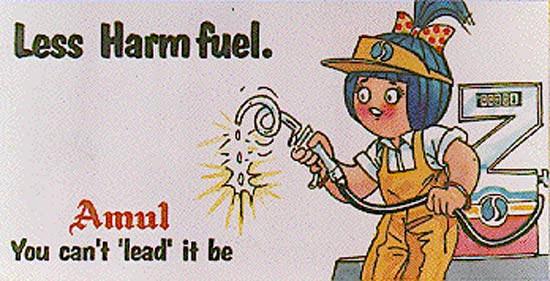

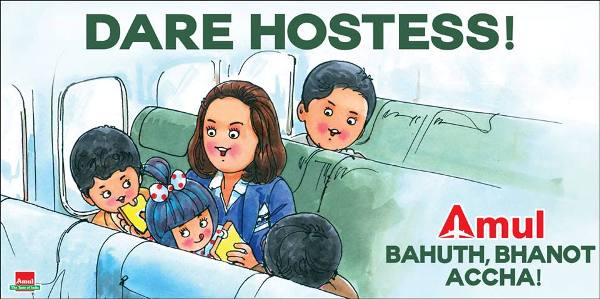

A brief history

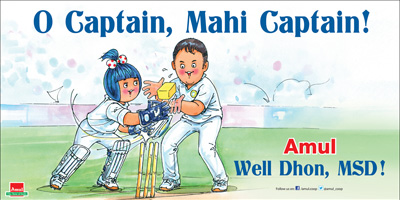

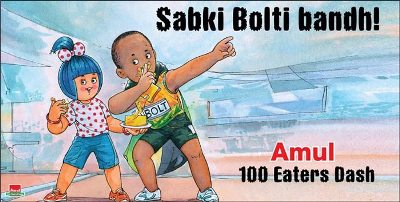

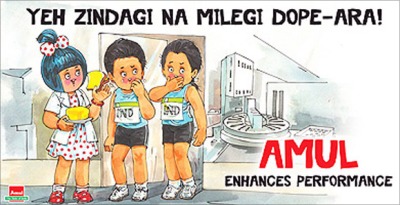

- The Amul girl has been the cheeky, one-line commentator on the zeitgeist for 50 years

- In 1966, the Amul campaign was started by Sylvester daCunha along with illustrator Eustace Fernandes and Usha Katrak and a few others

Rahul daCunha inherited the Amul campaign from his father in the early 1990s.

Amul Girl turns 50: Meet the three men who keep her going

The noseless girl with blue hair has been nosing around in her red polka-dotted frock. She looked up at Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the summer of 2014 with the oneliner Accha din-ner aaya hai.

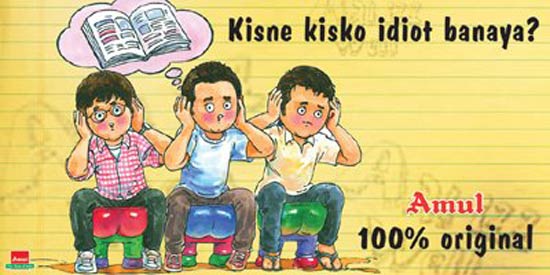

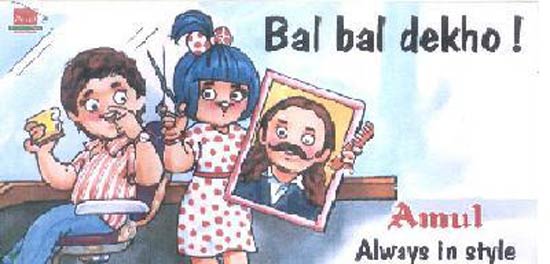

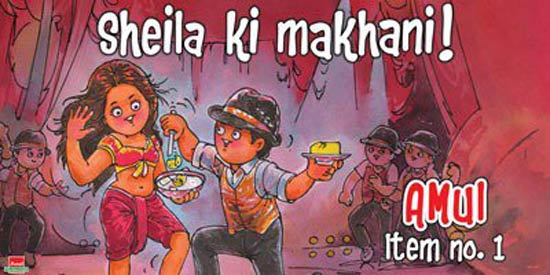

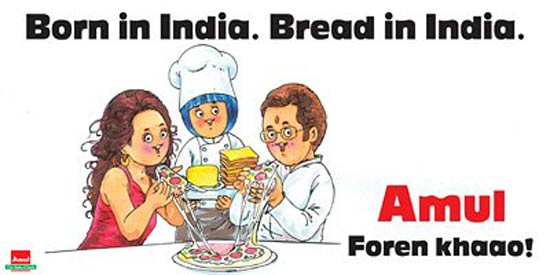

When his monogrammed suit was being auctioned, she cheekily smiled with the tagline "And the highest court is...". The Amul girl, a buttered toast in one hand and a prompt oneliner on her lips, has been a commentator on the zeitgeist for 50 years — from sterilisation during the Emergency ("We have always practised compulsory sterilisation," says the Amul girl, holding a salver of butter and with a cunning innocence that would have tied up even Indira Gandhi's censors in knots) to Aamir Khan's statement on growing intolerance (Amul girl offered a golden slice and asked him Aal izz hell or aal izz well?).

When Amul tweeted a birthday wish last month to Modi, who has been the butt of its butter jokes, he replied, "Thank you. Your sense of humour has always been widely admired." The Amul girl is the nice brat who gets away with it: her wide-eyed innocence is a counterpoint to her stinging wit, her young looks are balanced by her weighty statements, her hand-painted nostalgia is offset by her on-the-ball cool. "As India gets darker, the campaign is a ray of sunshine to make people laugh about what they are feeling dark about," Rahul daCunha, creative director of daCunha Communications and the man driving the Amul campaign, tells ET Magazine.

Daily Butter

The Amul campaign was started by daCunha's father Sylvester daCunha in 1966 along with illustrator Eustace Fernandes and Usha Katrak, among others. It was a prestigious account, but the ads had been staid and stuck to the basic brief of selling butter. When Sylvester took over, he decided to pitch it differently. "My dad realised that there was only so much one could say about food," says Rahul.

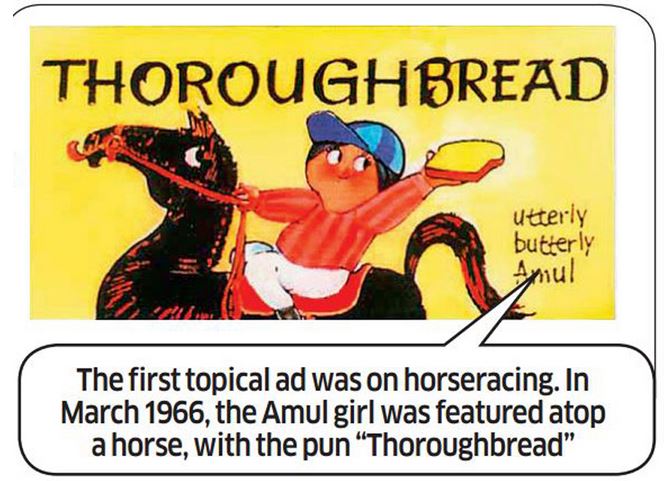

"There was no television and print was wildly expensive. An outdoor hoarding was a good way to inform people." The first topical ad came out in March 1966 when horse racing was becoming big. It featured the Amul girl riding a horse, with the word "Thoroughbread", followed by the famous slogan, Utterly Butterly Delicious. Rahul daCunha inherited the Amul campaign from his father in the early 1990s.

All through his childhood and youth, he says, his father gave him paltry pocket money with the justification that he would give him the Amul campaign. While passing it on, Sylvester had a word of advice for his son: don't "get into too much trouble, but say things the way they need to be said". During Sylvester's time itself, a Mumbai hoarding on Ganesh Chaturthi went Ganpati Bappa More Ghya past(Ganpati, Eat More), a play on the festival cry Ganpati Bappa Morya, and earned the wrath of Shiv Sena members who threatened to vandalise his office. Under Rahul, the campaign increasingly commented on politics, films and sports, but stayed clear of religious issues. The ads became controversial nevertheless. When allegations were swirling around Jagmohan Dalmiya, former chief of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, an Amul hoarding showed him in the manner of "hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil" monkeys and a tagline that went "Dalmiya mein kuchh kala hai?".

Dalmiya threatened to sue Kurien for Rs 500 crore, says daCunha. Last year, British Airways too called the agency to express its displeasure, when it was dubbed "British Errways" after Sachin Tendulkar's luggage got misplaced. Manish Jhaveri, the sole copywriter for the Amul campaign, says its vocabulary got a distinct stamp in 1995. When there was a leadership tangle involving PV Narasimha Rao, Sonia Gandhi and VP Singh, Amul came up with the line Party, Patni Ya Woh, a take on the film Pati, Patni Aur Woh. Jhaveri says the ad established Amul's style of punning, borrowing from popular culture and mixing the colloquial and regional with the formal.

Pushing the vernacular flavour, Amul has done campaigns in Tamil, Gujarati, Bengali and Punjabi as well. daCunha says the fearlessness of the Amul campaign has trickled down from the visionary Verghese Kurien, who established the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) that sells its products under the Amul brand. When Dalmiya threatened to take Kurien to court, he called daCunha and asked him to put up a fresh board outside Dalmiya's office in Kolkata. This one would have a fourth Dalmiya, covering his pelvic area with his hands.

Thankfully, it didn't come to that, but the bold streak has endured even after Kurien's death in 2012. "We believe in consistency. We have never changed our ad agency," says RS Sodhi, managing director, GCMMF, about daCunha Communications. "They know what they are doing. We have faith in their work and we mostly don't even look at the drafts before they go up on hoardings."

Making of an Amul Ad

Amul has arguably the longest running hoarding ad campaign in India. It might also have one of the smallest ad teams. Apart from Da-Cunha and Jhaveri, who has been with the campaign for 22 years, the only other person integral to it is illustrator Jayant Rane, who has been sketching for 30 years. Their output has kept pace with the times.

"In the 1960s, we used to do one ad a month; in the '70s and '80s we did one every fortnight; in the '90s that increased to one a week; now we put out up to five ads every week," says daCunha, adding that they cannot afford to slacken the pace as a topic "will be dead in three days". The campaign's target audience is the multitasking, up-to-date and opinionated 16-25-year-olds who see the world through their smartphones and have really short attention spans. DaCunha says this is an audience that shifts sides and changes opinions at the drop of a hat. An ad has to catch them by the scruff of their neck when an issue is red-hot. Choosing a subject for an ad and deciding on the exact moment to come out with it is a science, says da-Cunha.

He uses the term "topic plus", which means an issue that affects the public psyche and elicits dynamic and not just one-dimensional reactions or black/white opinions.

The team consists of (from L) illustrator Jayant Rane, Rahul da Cunha, Manish Jhaveri, the sole copywriter who has been with the campaign for 22 years

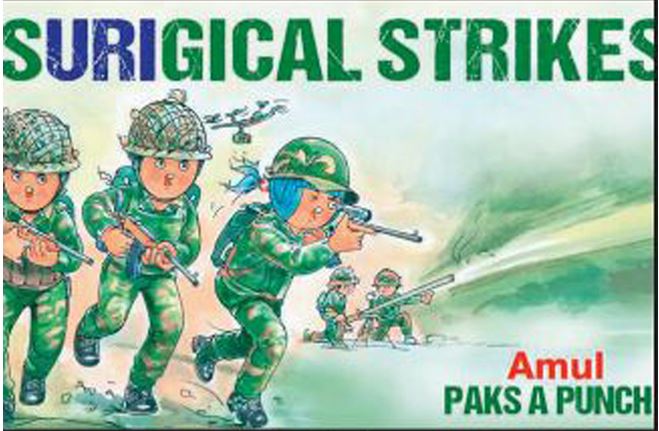

"For example, when Pakistan attacked Uri, I didn't know what people were feeling about it. I didn't know what our response as a country will be. Doing an ad sometimes involves holding back and waiting for public perception," he says. The waiting paid off. India carried out surgical strikes along the LoC, which led to Amul's "sURIgical Strikes". Social media has become the weather vane to gauge public perception. "I get the trend from newspapers. But I get the point of view from social media," says daCunha.

They now put out more ads on social media than on hoardings. This means Rane has to be extra careful with the detailing as illustrations are more vivid on a screen than on an overhead hoarding. For an ad celebrating the 500th Test match of Team India on September 22, Rane, for instance, searched for the exact shade of the cricketers' blazers.

What Not to Write

The Amul girl has withstood the test of time when many other mascots — Asian Paints' Gattu, the Onida devil or the Air India maharaja — have either been discarded by the brands (Asian Paints and Onida) or not been used to their full potential (Air India). DaCunha and his team know what has worked for the campaign, which is why it has undergone little change over the years. In an age of multi-generic art forms, the Amul ads are still painstakingly hand-painted by Rane. He was introduced to the Amul moppet through scrapbooks compiled by the previous teams.

He calls them "guide books" and has followed them. Rane says it's a stylistic decision to give the Amul girl's features — chubby cheeks, no nose, wide eyes and long eyelashes — to celebrities who are featured in the ad. Small allowances are made for discernible features such as Amitabh Bachchan's white French beard or Tendulkar's curly hair. The campaign has a list of favourite people and a checklist of attributes on what it takes to make it to the hoarding. Boring is out. Openness is in.

A person needs to have "failed or succeeded openly", says daCunha. In Bollywood, Bachchan is a favourite as are Shah Rukh Khan and Karan Johar. Among politicians, apart from Modi, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and his Tamil Nadu counterpart J Jayalalitha are preferred. Idiosyncrasies are a big draw — like Kejriwal's muffler and the facial features of Lalu Prasad Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav. But Mulayam's son and UP CM Akhilesh Yadav doesn't quite make the cut. Among businessmen, Vijay Mallya and the Ambanis have been covered often but Ratan Tata was drawn only once — when he retired, says daCunha. The ad has never used real people or thought of a brand ambassador. DaCunha says he is against roping in celebs for ad campaigns: "The star becomes more relevant than the product. I don't know any more what cricketer MS Dhoni advertises these days. Bachchan is every other brand."

All of this helps in keeping the Amul ads simple and cost-effective. Amul spends 1% of its total turnover on marketing, says Sodhi. GCMMF last year clocked a turnover of Rs 23,000 crore. Apart from daCunha Communications, ad agency FCB Ulka handles the advertising for Amul's other products. Piyush Pandey, chairman of Ogilvy & Mather India, says, "I think they have done a great job for decades," adding that maybe they should be more choosy. "They could do with being more selective to live up to their own standards.

Sometimes less is more." He says he wouldn't, however, change the old look and feel of the ads. "They stand out because of that basic art. Sometimes old is gold." The makers of the Amul ad are careful about what the Amul girl says. While public humour in India has changed, peppered with innuendos, the Amul girl indulges in none of that. "She is a kid," says daCunha. "She is also really old," he adds, pointing to the paradox that defines the Amul girl. Also, people feel responsible for her. A few years back, the Amul girl had featured as one of the characters in the ads. Once she was a cheerleader at an IPL match and daCunha faced angry comments on why she was portrayed in a short skirt. Now, he says, he tries to keep her at an objective distance, "as a commentator not a character". DaCunha employs people for production and admin work but doesn't hire anyone else for the campaign. Nor has he felt the need to take up another similar assignment.

"Anything else we take up will be an alsoran," he says. DaCunha is 54, Jhaveri 47 and Rane is 57. What about succession? They are not thinking about it. They are not even thinking about taking a long vacation. The trio say they almost never switch off from the campaign and are wired to work even on holidays. Rane hardly ever goes on vacations. When asked what would happen if some day Jhaveri asks for a three-month holiday, daCunha says: "I'd shoot him!" All this for the with-it girl with blue hair who loves her pun maska.