Afghanistan-Pakistan relations

m (Pdewan moved page Afghanistan to Afghanistan-Pakistan relations) |

(→Afghanistan) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

[[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | ||

[[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | ||

| − | = | + | =Deteriorating relations= |

| − | + | ==How Afghanistan was lost== | |

March 18, 2007 | March 18, 2007 | ||

Revision as of 13:31, 5 January 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Deteriorating relations

How Afghanistan was lost

March 18, 2007

REVIEWS: How Afghanistan was lost

Reviewed by Zubeida Mustafa

THE message that emerges powerfully from this nondescript looking but informative book is that for Pakistan the chickens of its Afghan policy are coming home to roost. The author, Dr Fazal-ur-Rahim Marwat, who is associate professor at the Pakistan Study Centre in Peshawar, packs so much information in From Muhajir to Mujahid that it is not easy to assimilate it in one reading. There are so many details, names and events thrown together randomly that it takes some time for the reader to get accustomed to the writer’s style. As one wades through the book, all the pieces fall in place like that of a jigsaw puzzle.

In the ’80s when the so-called Afghan freedom fighters were combating the Russian forces in Afghanistan, Pakistan consistently denied having a hand in the insurgency. The myth was faithfully perpetuated that the Afghans were fighting a war against the godless infidels and Pakistan’s only role was that of providing moral support to the Afghans. If Islamabad was extending any material assistance, it was in the form of economic aid and shelter to the three million Afghan refugees who had fled their home, it was claimed. Until he died in a plane crash in 1988, Ziaul Haq did not shift from this stance.

Even in the heydays of the Afghan war, there were critics who refused to accept the Pakistan government’s official line that it was not involved in Afghanistan militarily. Today no one would deny that Pakistan’s intelligence agencies were not simply backing the Afghan fighters — the so-called mujahideen — they were actually conducting their war for them. Their aim? To extend Islamabad’s control over Afghan territory by controlling the mujahideen. Thus it hoped to realise its age old dream of gaining strategic depth.

The truth of the Afghan war has been exposed by many writers. John Cooley (Unholy Wars), George Crile (Charlie Wilson’s War), Steve Coll (Ghost Wars), Ahmad Rashid (Taliban) and Mohammad Yusaf and Mark Adkin (The Bear Trap) tell the story of the Afghan war very comprehensively. Dr Marwat’s book is a replay of this narrative albeit with a new dimension. He adds his own personal insight and knowledgeable analysis to it. This makes the book a worthwhile source of authentic information on Afghanistan.

The general perception of the Afghan problem is that trouble in that country began with the Soviet military intervention in December 1979. But the fact is that the crisis had begun to build up much before that. Since the Saur revolution of 1978 that brought the PDPA to power in Kabul, Pakistan started meddling in Afghan affairs. Some Islamist militants, who fled their homes after Sardar Daud overthrew the monarchy in 1973, were armed by Pakistan and sent back into Afghanistan to destabilise that country. Since the power of the traditional leadership comprising maliks and tribal chieftains had been broken after the fall of the monarchy, it was easier for Pakistan to fish in the troubled waters of Afghanistan. The United States also jumped into the fray and supplied arms to the insurgents.

The Soviet invasion forced difficult choices on Pakistan. It could either acquiesce in the Soviet presence across the Durand Line or confront it. It chose the latter but in typical Ziaul Haq style. Officially Pakistan’s policy took the form of vehement protest in international forums against the Soviet “invasion”. Covertly Pakistan provided active assistance to the Afghan resistance. In this way Islamabad hoped to preempt any Soviet expansion southwards and win the backing of the west without incurring the risk of a direct attack from the Russians. The aim was also to win access to Afghanistan.

The formulation of Pakistan’s Afghan policy involved a number of actors the most significant being the army leadership comprising the key generals and corp commanders, the president, the finance minister and the foreign minister. An infrastructure was also created to formulate the strategy and trap the refugees in the CIA/ISI’s scheme of things. The main institutions set up were the Afghan cell and the Afghan Refugee Commissionerate. The cell met frequently and operated above the foreign ministry.

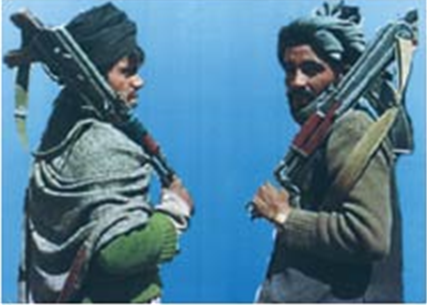

The Afghans leading the insurgency grouped themselves into parties, some of which were Peshawar-based and others were closer to Iran. Every refugee was forced to declare allegiance to one party or the other — that was the only way he could draw his rations. Thus the simple muhajir became the gun-wielding mujahid and provided cannon fodder to the freedom struggle. That would also explain why the mujahideen had to work hard to indoctrinate the refugees. In this context the schools that were set up to educate the refugee children served a useful purpose. Textbooks preaching jihad and developed by the Americans proved to be an effective tool.

Pakistan’s goal was to establish its influence in Afghanistan via the mujahideen. It could not succeed in its mission mainly because the various Islamist parties failed to come together for a common cause. The infighting among them intensified so much so that it became impossible for them to operate as a single force. At one stage 48 groups were conducting the jihad in Afghanistan. But they were working at cross-purposes. Pakistan was also a factor in this fragmentation because it had its favourites who were shamelessly promoted — Gulbadin Hekmatyar being the most notorious. Naturally enough this approach weakened the mujahideen who at one time were believed to have 73,000 fighters and 151,000 supporters.

The convergence of Ziaul Haq’s interests in Afghanistan with America’s global strategic goals helped both sustain and win the war. But it was a Pyrrhic victory as we know today. What was jihad for the Islamists, badal (revenge) for the common Afghan and a political coup against the Pakhtoon nationalists for the military leadership in Islamabad resulted in the “de-secularisation”, “de-liberalisation”, “kalashnikovisation” and the “Talibanisation” of Afghanistan. The educated classes and the intellectuals were wiped out or driven away from the country leaving it in the hands of an ignorant and obscurantist leadership — until 9/11 changed the scenario.

Dr Marwat very strongly concludes that violence does not bring durable peace. The solution lies in a political dialogue. The author does not, however, offer any way out of the present morass which has spread through the region.

From Muhajir to Mujahid: Politics of War Through Aid By Dr Fazal-ur-Rahim Marwat Edited by Dr Parvez Khan Toru Pakistan Study Centre, University of Peshawar ISBN 969-8928-03-0 243pp. Rs300 Reviewed by Zubeida Mustafa