1971 War: Indian accounts

(→B) |

(→Operation Mandhol/ 9-Para Commando unit) |

||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

| − | =Prisoners of war= | + | = Prisoners of war = |

[[Category:Defence|1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS | [[Category:Defence|1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS1971 WAR: INDIAN ACCOUNTS | ||

Revision as of 19:45, 29 January 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The timing of the military campaign in East Pakistan

Air Vice Marshal Arjun Subramaniam (retd) ‘s argument

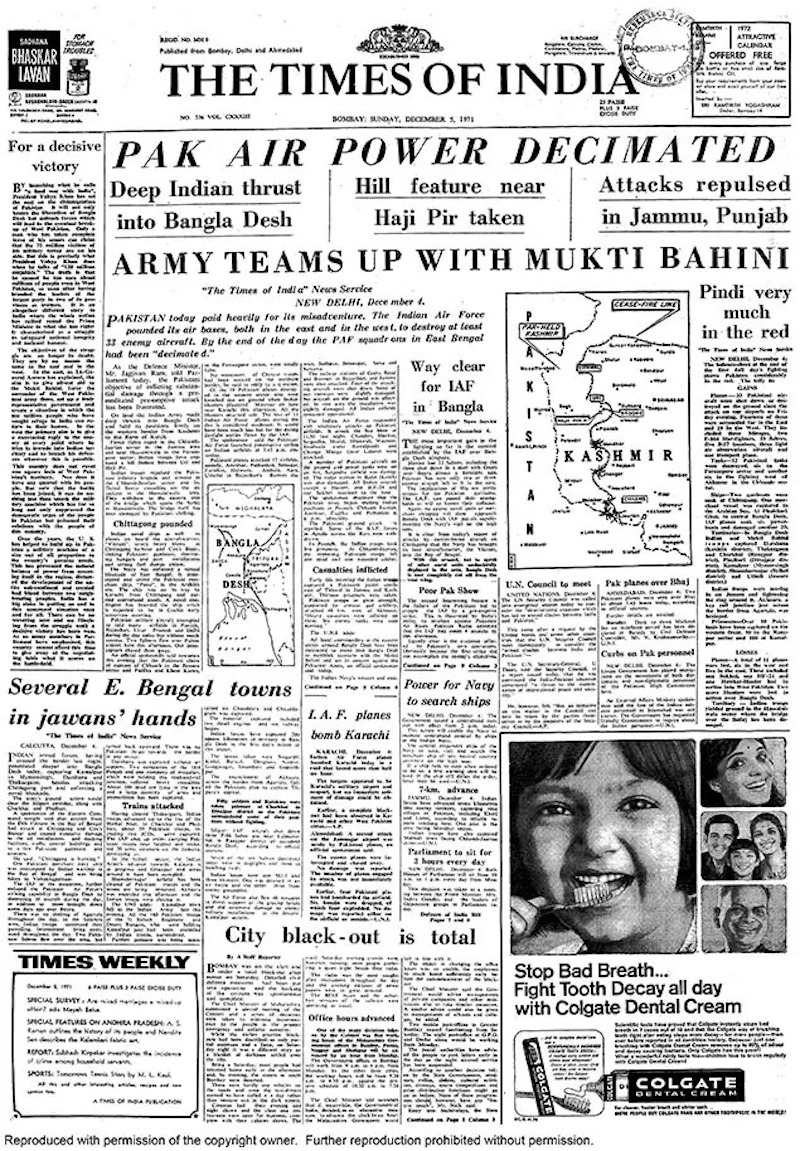

ARJUN SUBRAMANIAM, Nov 28, 2021: The Times of India

The attempts to undermine the contribution of Indian Army’s iconic army chief, General (later Field Marshal) Sam Manekshaw, to the strategic decision-making process in the run-up to the 1971 war are unfortunate. Two recent books by a former union minister, Jairam Ramesh (Intertwined Lives: P N Haksar And Indira Gandhi) and a seasoned diplomat, Chandrashekhar Dasgupta (India and the Bangladesh Liberation War: The Definitive Story), have contested the largely accepted narrative that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi delayed the military campaign in East Pakistan from April-May 1971 based on her army chief ’s advice. Dasgupta uses his superior linguistic skills to condescendingly portray Manekshaw as a raconteur. He also suggests rather sensationally in a recent interview that the idea of delaying India’s military campaign in East Pakistan was essentially Indira Gandhi’s idea and that she used her army chief to create the final narrative. Ramesh though gently calls this a ‘story bequeathed to us’.

There are two issues at play here that need to be dissected. It is quite clear that both Ramesh and Dasgupta have drawn very heavily on the memoirs and papers of P N Haksar and P N Dhar, two of Indira Gandhi’s closest advisors in the PMO and quite legitimately, her spin doctors. It is also evident that in the aftermath of the Shimla Accord where India failed to capitalise on a military victory by extracting adequate strategic concessions from Pakistan, both Haksar and Dhar worked overtime to retain PM Gandhi’s image as the ‘be all and end all’ of India’s 1971 campaign. Every single military historian, including this author, have recognised PM Gandhi’s stellar role in orchestrating the 1971 victory, but surely, it was not a single-handed effort! Dasgupta’s lack of graciousness and the unwillingness of Ramesh to take into considerations any recollections of the time by Indian Army officers involved in the planning process, induce an unnecessarily condescending twist to what was merely an army chief doing his job and ‘speaking truth to power.’ Even more galling is Dasgupta’s suggestion that Manekshaw lacked an understanding of geopolitics — this too reflects the myopic approach of yesteryear within Indian intelligentsia that ‘generals know little about anything else other than war fighting.’ Sam Manekshaw’s firm advice to PM Indira Gandhi about the perils of getting bogged down by the monsoon in riverine East Pakistan is well recorded in three books on Manekshaw by Major General Shubhi Sood and Brigadier Panthaki, his ADCs, and Lt Gen Depinder Singh who served as his military advisor. Even more robust are Lt General BT Pandit’s recollections of a morning in late March 1971 at the Military Operations (MO) Directorate in an interview that is part of the author’s oral history collection. Pandit, a future corps commander, was then a major in charge of logistics planning at Army headquarters. He would go on to command his engineer regiment during the Battle of Basantar as a lieutenant colonel and win a Vir Chakra for gallantry. Pandit recalls those momentous days of planning when Manekshaw was clearly seeking continuous validation from his staff to support his operational assessment that victory could not be assured should the Indian Army launch immediate operations against East Pakistan in April 1971. Sealing that decision was a clear assertion by Pandit to his chief that should the Indian Army be pushed into operations in April, sustaining one thrust line could be supported logistically in a time-frame of two-four weeks, and that putting together two or more axes of advance would take three months. The rest is recorded history wherein six months of stocking and planning resulted in four thrust lines into East Pakistan that both physically and psychologically overwhelmed the Pakistan Army.

However, India’s armed forces and particularly, the Indian Army, must accept that it has been unable to institutionally set this record straight due to the non-availability of any recorded minutes of all these important discussions that should/may have existed in the MO Directorate. These could then have been declassified to help historians deconstruct those momentous months for posterity. Instead, we have this undesirable jostling for space that is largely based on the personal papers of two influential officials in the PMO and a clutch of military biographies by Manekshaw’s military advisors and ADCs. In this melee, the clearest confirmation of the trajectory of events was his wistful response to Major Pandit’s timelines when he remarked ‘that bloody well takes me slap bang into the middle of the monsoons.’ Clearly, that planning conference indicated that Manekshaw understood the gravity of the refugee crisis, wanted to support his Prime Minister’s desire for speedy military action, but heeded sound military advice from subordinates and did not hesitate to speak truth to power in pursuit of larger national interest.

Air Vice Marshal Arjun Subramaniam (retd) is a military historian and author of India’s Wars and Full Spectrum

Dec 16, 2021: The Times of India

Lesson we learnt: Together we fight and…win

Teamwork worked

Till the 1971 war, the Indian Army had an overwhelming presence and impact on military decision-making. The sub-optimal operational outcomes of the 1965 India-Pakistan conflict forced India’s strategic establishment to look at a holistic development of military capability and much effort went into adding heft to sea power and air power. Consequently, the Indian Navy and Indian Air Force truly came of age during the 1971 conflict, striking telling blows across all sectors and theatres of conflict. Cementing this transformation was the ability of both Admiral Nanda and Air Chief Marshal Lal to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the dominating Sam Manekshaw and remind him of the growing importance of sea power and air power in modern warfare. While there was no integrated planning process prior to the conflict, a good beginning was made in the run-up to the conflict wherein all three services shared their final plans with each other. This resulted in a plug-and-play approach that allowed the navy and IAF to impact ground operations in a way never experienced before.

Planning and preparation

In March 1971, General Sam Manekshaw unambiguously indicated to PM Indira Gandhi at a cabinet meeting why India must not go to war before December 1971. To Indira’s credit, not once did she pressure Manekshaw or berate him for standing firm. But having gained breathing time for six months, the ball was now in the court of India’s armed forces to plan, prepare and deliver – which they did. Even as the Pakistan Army frittered away operational bandwidth by dabbling in politics on the west and engaging in genocide in the east, the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force worked on their strategy of multi-pronged offensive in the east and proactive defence in the west.

Seize the initiative

Several instances of calibrated initiative can be highlighted during the conflict, whether it was the ‘bash on regardless’ flavour of 54 Infantry Div under Maj Gen W A G Pinto in the Battle of Basantar; the insistence of Admiral Nanda to push his ‘killer squadron’ of missile boats to the limit while attacking Karachi; or the initiative shown by Wing Commander ‘Mini’ Bawa in launching the full might of his Hunter squadron to repel a Pakistani armoured assault at Longewala and converting it into a graveyard for their tanks. However, if there is one instance of operational initiative that stands out, it stemmed from a simple statement from Lt Gen Sagat Singh, the hard-driving corps commander of IV Corps that was making a dash on Dhaka from the east. Halted in his advance by the Meghna River and its tributaries, he turned to his air force adviser, Gp Capt Chandan Singh, and remarked, “I want to be the first into Dhaka, get me across the Meghna dammit.” The rest is history as Chandan Singh, supposedly without seeking much guidance from higher formations, orchestrated a series of heliborne landings with his Mi-4 units at multiple places across the Meghna and put Sagat at the doorsteps of Dhaka. This, along with the Tangail paradrop to the northwest of Dhaka, broke the will of the Pakistani forces to fight against an enemy that appeared larger than what it was. Though the capture of Dhaka was never on the plate when operations commenced, it was the speed and initiative with which Sagat progressed that made it possible to force a strategic outcome.

Leading from the top

Good leadership is non-negotiable in any professional military, but for it to permeate across ranks and levels in battle, it must begin at the top and 1971 saw military leadership taken to a new level as the three chiefs had the pulse of the various battles and campaigns always. This involvement was reflected by instances such as the army and air chiefs ringing up an IAF An-12 squadron separately to congratulate it after a spectacular night raid on a Pakistani artillery brigade at Haji Pir.

As we commemorate 50 years of the 1971 war, let us remember these enduring lessons from a transformative moment in contemporary Indian history.

Battles

The important ones

Dec 14, 2021: The Times of India

Basantar is a tributary of the Ravi in Punjab. The 12-day battle of Basantar took place in the Shakargarh ‘Bulge’, which is a protrusion of Pakistan’s boundary into Indian territory. It was a strategic area comprising road links to Jammu from Punjab that Pakistan could have cut off.

Pakistan had opened up the Western sector to divert Indian troops from the Eastern front in Bangladesh and prolong the war. To gain advantage through the element of surprise, the Indian Army attacked Pakistani positions in the Jarpal area, triggering the Battle of Basantar on December 4.

Despite being at a disadvantage, Indian troops made massive gains during the final days of the battle and also repelled the Pakistanis. They continued the military thrust deep inside Pakistan and came close to the Pakistan Army base at Sialkot. Expecting another massive assault by India, and in no position to launch counter-offensive operations in the region, Pakistan offered unconditional surrender, which led to the ceasefire. India gained control of more than 1,000 square miles before finally settling on 350 square miles of Pakistan territory.

Battle of Longewala

On the intervening night of December 4-5, 4,000 Pakistani soldiers and tanks attacked Longewala border post, a strategic point on the Western frontier. Pakistan assumed the attack would help its 1st Armoured Division in the Sri Ganganagar area. Its troops crossed the border at 1am on December 5, and its tanks came within sight of the Indian post at about 4.30am. At 7am, Indian Air Force planes attacked and knocked out many Pakistani tanks. There were several attacks over the day, but Indian troops repulsed them each time.

At 3.30pm the enemy made a full assault with tanks but the Indian troops held their ground and the IAF turned the scene into a graveyard of Pakistani tanks. In all, 37 tanks were destroyed and the enemy left behind 250 vehicles. Indian troops pursued the Pakistanis through the night of December 5-6 and captured Manitwala post 10km inside Pakistan territory. The ceasefire saved Pakistan further losses.

Meghna Heli-Bridge

By December 8, territory leading up to the Meghna River had been occupied as part of the Dhaka Campaign but a Pakistani division had turned the Ashuganj Bridge, the only way across the river, into a fortress. However, Indian troops steamrolled past them with a daring improvisation of heli-borne and river crossing operations. Through the night of December 9, the IAF air-lifted the entire 311 Brigade. Around 600 troops landed first. Over the next 36 hours, more than 110 sorties were flown. While this operation was on, 73 Brigade moved across the Meghna on boats and riverine crafts. After consolidating their positions at Raipura (south of the bridge), the troops were heli-lifted to Narsingdi, 50km from Dhaka. They captured Daudkandi in Comilla and Baidder Bazar in Narayanganj on December 14 and 15, respectively, both with helicopter assaults. After that, the metalled road to Dhaka lay undefended for 4 Corps to take.

Tangail Airdrop

The main objective of this operation mounted on December 11 was to capture the Poongli Bridge on the Jamuna River, to cut off the Pakistani 93rd Brigade retreating from Mymensingh in the north to defend Dhaka.

The paradrop at Tangail, along with the Indian Army’s speedy advance, unnerved the Pakistani commanders. The bridge’s capture gave access to the undefended Manikganj-Dhaka Road and prevented the retreating Pakistani troops from reaching Dhaka.

Operation Trident

In November 1971, the Western Fleet of the Indian Navy was given a broad directive to prevent any reinforcements from reaching the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan. The port of Karachi housing the Pakistan Navy headquarters was to be blockaded.

On December 3, an Indian Navy force sailed from Bombay to Diu. At 5pm on December 4, when it was 240km from Karachi, orders to commence Operation Trident were given. Missile boats closed in on Karachi at full speed in the dark, and launched their missiles. The shocked Pakistanis thought it was an air attack. This daring raid sank PNS Muhafiz, PNS Khyber, and Merchant Vessel Venus Challenger, besides Pakistani morale.

Battle of Longewala, December 5-6, 1971

Ajay Sura, Dec 12, 2021: The Times of India

The battle of Longewala on December 5-6, 1971 was one of the first major engagements in the western sector. It took place at the Indian border post of Longewala, in the Thar desert of Rajasthan.

A company of 120 soldiers of the 23rd battalion of the Punjab Regiment, led by Chandpuri, who was then a major, managed to hold off around 3,000 troops of the 51st Infantry Brigade of the Pakistani Army, backed by the 22nd Armoured Regiment, for two days until the Indian Air Force arrived to thwart the Pakistani assault. The battle went on to be made into the blockbuster film Border.

In an interaction with TOI before his death in November 2018, Chandpuri revealed that during the battle, he had kept a loaded carbine with him. He intended to use it to shoot himself if he was captured by the Pakistani troops. “I decided to die on my own rather than becoming a prisoner of war,” Chandpuri said. Fortunately, he never had to use it on himself.

Surinder, now in her late seventies, said she came to know that the war was about to begin only on December 4, 1971, at the Nawanshahar bus stand in Punjab while she going from her in-laws’ house in Saroa village to Chandigarh.

"I told my mother-in-law about it on reaching Chandigarh. She said a 'jyotishi' (astrologer) who was a family friend had happened to come to their home and assured her that Major Chandpuri would return home unscathed and also that he would be honoured and celebrated after the war. I was still not satisfied and brushed everything aside, not knowing that the panditji’s prophecy would come true,” said Surinder.

Surinder said also she came to know of her husband being awarded the country’s second-highest gallantry award, the Maha Vir Chakra, through the radio. “My father heard about gallantry awardees on AIR. Initially, he did not inform me as there was some confusion because some awards were announced posthumously. It was only after confirmation that he told us about it,” she said. The two were married in 1967 and the couple have three sons.

Major (later Brig.) Kuldip Singh Chandpuri

How he motivated his troops

Surinder described her husband as a “very honest, simple person who would stand strong for what he felt was right." "He always gave the credit of winning the battle to his troops and the IAF. He looked after his soldiers like his own children. They still come to our home and remember the days they spent with him,” she said with moist eyes.

Some years ago, her husband Chandpuri, in the interaction with TOI before his demise, had recalled the visit of Field Marshal R M Carver, who served as chief of the British army and then the chief of defence staff, to the site of the heroism a few weeks after the war.

Chandpuri said Carver wanted to know what motivated him to stay put even after seeing the substantial size of Pakistan troops moving towards the post and how he kept his troops motivated. To the first question, Chandpuri replied, “Sir, I was given a task in writing and I had to complete it until changes were received from the Army in writing. I just executed what I was asked to do by my seniors.”

As for how he had kept his men motivated, Chandpuri, then a young major, said, “I just told them about the sacrifices made by the armed forces and the Sikh community, especially Guru Gobind Singh, as most of the troops were from Punjab. I told my jawans that I would not leave the post and anyone willing to go could leave. They relied on me and we managed to hold the post till the arrival of the IAF.”

Chandpur also remembered the timely entry of the IAF. "They came when they were needed the most," said the war veteran. According to Chandpuri, initially, IAF pilots were conducting sorties but not firing on Pakistan tanks. When he asked headquarters for the reason, he was told that the IAF pilots could not distinguish between Indian and Pakistani tanks. “I told them we had not deployed any tanks and all the tanks visible to the pilots belong to Pakistan. Soon after, the IAF destroyed most of the Pakistan forces in a short time,” he said.

Why J P Dutta waited for 25 years to make Border

Chandpuri also revealed why filmmaker J P Dutta waited for 25 years to make the film Border. He said the story of the Longewala battle was narrated to the Dutta family immediately after the war by J P Dutta’s brother, Squadron Leader Deepak Dutta, who was a flight lieutenant during the 1971 war.

“Deepak told J P Dutta and his family at their Mumbai house about the remarkable story of Longewala, where 120 men led by me saved a strategically important post, fighting a 3,000-strong assault force of the Pakistan army. Later, Deepak died flying the newly-inducted MIG during the conversion of Hunter aircraft to MIG in the IAF,” Chandpuri said.

After his brother's death, J P Dutta decided to make a film based on the battle. But, he had to wait because the Official Secrets Act forbids sharing of details of war for 25 years. Overwhelmed by the bravery shown by the men on the border, Dutta waited. In 1996, he finally got permission from the ministry of defence (MoD) and made the film, Chandpuri told TOI.

Chandpuri's role was played by actor Sunny Deol. His wife Surinder's role was essayed by Tabu.

How the temple stayed intact

When the war broke out, the Army took over the Longewala post from the Border Security Force (BSF). During the handing over ceremony, a BSF inspector hesitantly requested Chandpuri to look after a small temple maintained by them. Chandpuri told TOI, “I told him that the Army had taught us to hold all religions in high esteem. I immediately deployed a havildar of my company to maintain the temple. Even heavy shelling from Pakistan could not damage the temple. I still believe it has miraculous powers and saved my troops,” Brig Chandpuri had said. The war veteran used to visit the temple even after his retirement.

Role of the IAF

Rajat Pandit , February 19, 2021: The Times of India

The IAF now wants to debunk the conventional narrative, reinforced by blockbuster movie ‘Border’ in 1997, that the famous battle of Longewala was primarily won by the gallantry shown by the 120 infantry soldiers led by Major Kuldip Singh Chandpuri during the 1971 war.

A new book, ‘The Epic Battle of Longewala’, written by Air Marshal Bharat Kumar (retd) after extensive research, contends it was actually airpower that decisively won the battle against Pakistan’s major armoured thrust at the Rajasthan border outpost on December 5-6, 1971. A force of just six Hunter ground-attack jets based at the Jaisalmer airbase “destroyed or damaged over 40 Pakistani tanks” in attacks, making the rest of the tanks as well as the Pakistani infantry scurry back across the desert.

Releasing the book on Thursday to mark the 50thanniversary of the 1971 war, IAF chief Air Chief Marshal R K S Bhadauria said the “audacious” and “brilliant” Pakistan plan to launch the thrust along the “unexpected” Longewala-Jaisalmer axis could have changed the course of the war.

Pakistan, however, forgot to factor in IAF’s ability to strike. “Airpower can bring asymmetric results if the time and place are chosen correctly,” he said, endorsing the “detailed and accurate account” of the battle in the book.

‘Battle wasn’t won the way depicted in film’

Chandpuri, incidentally, was decorated with the country’s second-highest wartime gallantry medal, the Maha Vir Chakra, for the way he and his company of Punjab Regiment soldiers bravely held their post despite repeated Pakistani attacks till the Hunters could arrive on their bombing missions. He later became a brigadier and passed away in 2018.

The book, however, contends the J P Dutta-directed film erroneously depicts that the battle was “single-handedly” won by the Army company against all odds, with the IAF playing only a peripheral role in the defeat of the attackers. In the film, Chandpuri’s role was played by Sunny Deol. “While one does not want to belittle the courageous role played by the Army personnel who faced the enemy at Longewala, it must be emphasised that the battle was not fought the way it has been depicted in the film,” it says.

The attack by Pakistani forces had reached Longewala at about first light on December 5 and decided to neutralise the Army post there. “By this time, the first pair of Hunters loaded with T-10 rockets and 30mm Aden guns were already airborne from Jaisalmer,” writes ACM Bhadauri in the book’s foreword. “Thereafter, there was no respite for the Pakistanis as wave after wave of Hunters decimated the enemy armour,” he adds.

The book contends that a popular movie erroneously depicts that the IAF played only a peripheral role in the battle of Longewala

Operation Mandhol/ 9-Para Commando unit

B

Ajay Sura, Dec 12, 2021: The Times of India

CHANDIGARH: A team of 120 Para Commandos of the Indian Army was given the task to raid and destroy enemy’s artillery guns positioned inside Pakistan territory during the 1971 war.

The military engineers told them that 3kg of plastic explosive would be enough to damage the guns, the commanding officer of the unit, however, asked the raiding team to “add 2kg extra for luck”. The raid, popularly recognised as Operation Mandhol is considered to be the first surgical strike by Indian Army’s Special Forces inside enemy territory.

The raid had also forced the Pakistan army to raise a second line of troops to secure their artillery guns, thereby changing their military doctrine.

Recalling the war, Colonel K D Pathak (retd), who was then a captain and second-in-command (2-IC) of the company that carried out the raid, said during the night of December 13/14, 1971, his unit was assigned the task of destroying Pakistan’s artillery guns positioned near Mandhol village — around 19km southwest of Poonch. Six 122mm Chinese guns of Pakistani battery were creating trouble for 93 and 120 infantry Brigades of the Indian Army. The 9-Para unit was then posted at ‘Nangi Tekri’ post at the height of 4,665 feet in Poonch sector in Jammu and Kashmir.

One of the renowned veterans of special forces, Col Pathak, 80, said their company comprising five officers and around 120 men, led by Maj C M Malhotra, started around 5.30pm on December 13, 1971.

“It was a cold night and they had to cross neck-deep water of the Poonch river to reach Mandhol. On reaching the village, they found it completely deserted. After tracing the gun positions, the party was split into six groups with each attacking one gun. After a fierce battle with the enemy, all guns were destroyed with the help of pencil-cell connected timer explosives. During the fight, many soldiers of the Pakistan army were killed while several fled,” recalls the veteran.

Prisoners of war

Fl Lt (later Air Commodore) Jawahar Lal Bhargava

Ajay Sura, Dec 12, 2021: The Times of India

From: Ajay Sura, Dec 12, 2021: The Times of India

CHANDIGARH: After getting free from the torturous one-year confinement in Pakistan as a prisoner of war (POW) during the 1971 Indo-Pak war, the most shocking thing that came before Air Commodore Jawahar Lal Bhargava, then a young flight lieutenant, on reaching India, was when his kids called him “uncle”.

“When I met my son Sandeep and daughter Suniti on reaching India on December 1, 1972, both of them were curiously staring at their mother wanting to know who I was. After a while, my son came and said 'hello uncle'. I broke down," said the 79-year-old war veteran. "All I could say in reply was 'fine, beta.'"

A native of Patiala, Bhargava said his son was three and daughter was just one-and-a-half years old when he was captured in Pakistan. Fifty years later, his son is part of the Indian Air Force as an officer and his daughter is married to an Indian Army officer.

Bhargava was among the 12 air force pilots, 7 army officers and 600 soldiers who were made POW in Pakistan during the 1971 war and were released in December 1972, after almost a year in captivity. Only two, who were sick and wounded, were released earlier – in February 1972.

Bhargava recalled the day – December 1, 1972 – when he along with other POWs returned from Pakistan. They came via the Wagah border where the then chief minister of Punjab, Giani Jail Singh, received them. Initially, they were taken to the local air force unit, where chilled beer and a sumptuous lunch were arranged. Thereafter, they were flown to the Palam air force base, where they were united with their families.

Bhargava, who is also a former Ranji cricket player, said he considers his wife Anu more courageous than him since she had to face a lot of trauma in his absence. “When news about the crash of my aircraft was told to her, she told everyone that nothing will go wrong and that I would return,” he said.

Bhargava said his family came to know that he was likely to be alive when his parachute, ejection seat and G-suit were found by an army search team and the same were handed over to his squadron. "From these items, it became evident I was alive, but where the hell I had disappeared no one knew,” he recalled.

Later, in mid-January 1972, his family was informed about his POW status in Pakistan.

How he was caught Bhargava said he was struck down during his first sortie in the enemy area, soon after he took off from the air force station in Barmer, Rajasthan, on the morning of December 5, 1971 to launch an attack.

At around 9am, his aircraft was hit by ground fire and he decided to eject. His parachute had barely opened when he touched down. His aircraft crashed into the sand dunes on the Pakistan side adjoining Rajasthan.

He immediately took out some important items from the survival pack, buried his G-suit under the bushes, set his watch to Pakistan standard time and started walking away from the aircraft.

He said he managed to survive for around 12 hours without being identified. Introducing himself as a pilot, Mansoor Ali, of the Pakistan air force, he told villagers his plane was shot down by Indian forces. He even showed Pakistan currency to convince them.

However, he came across some Pakistani rangers in a village. One of the officers asked him to read the Kalima (testimony of Islamic faith). "As I failed to read that, I was exposed. I was arrested and handed over to the Pakistan army," he said.

A traumatic year in captivity

Bhargava said he spent close to a year in Pakistan as a POW after his HF-24 9 (Hindustan Fighters) aircraft, popularly known as “Marut”, was shot down.

"The defence officers in Pakistan behaved decently with Indian soldiers in captivity but a pilot has to go through a traumatic period in responding to their queries. They would not allow you to sleep and would keep asking about your squadron and other classified information. It is really difficult to say no for every query," he said.

When he was asked to reveal the names of other pilots of his squadron, Bhargava said he stated the names of his siblings and cousins instead. "I had to make sure to repeat the same names to other investigators, as lots of agencies grilled the pilots in such situations. I remember they asked me who is the best pilot of your squadron and I replied – 'He is in front of you,'" he said.

Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra radio station

Priyanka Dasgupta, Nov 28, 2021: The Times of India

A quiet road in Kolkata’s Ballygunge leads to a nondescript two-storied house whose entrance is lined with deodar trees. But the current owners of Gupta House on 57/8 Ballygunge Circular Road, a stone’s throw from where legendary actress Suchitra Sen once lived, are unaware of its tryst with history. Fifty years ago, their residence had housed a secret radio station that played a vital role in liberating Bangladesh in 1971.

Yet, some 7,388 km away in Heidelberg, Germany, 74-year-old Abdullah Al-Farooq still feels an adrenaline rush when he sees a photo of this white house where he worked for the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra from May 25 to December 21, 1971.

According to Dhaka-based stage and film director Nasiruddin Yousuff, who is also a muktijoddha (freedom fighter), other radio stations were important as well. “Akashvani Kolkata, BBC and Voice of America also played an important role by broadcasting war field news on a regular basis,” he says. Yet Mutassir Mamoon, who holds the Bangabandhu Chair at Chittagong University, insists that the impact of Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra was “unique”. “People of Bangladesh tuned in just to get inspired,” he said.

Farooq rewinds to the momentous day on March 26, 1971 when ‘Bangabandhu’ Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s declaration of independence was aired. Poet Abdus Salam read out a fiery text asking Bengalis to resist the invading Pakistani army. On March 28, the word ‘revolutionary’ was dropped and the station was named Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra. Soon ‘Joi Bangla, Banglar Joi’ became the radio’s signature tune.

Broadcasting continued till the transmission building in Bangladesh got bombed by Pakistan on March 30. Farooq’s reminiscences sound like a thriller as he describes their miraculous escape and how they carried their KW mobile transmitter in a truck to Ramgarh on the Tripura border. The next broadcast began on April 3 after they reached BSF 92 headquarters at Bagafa. A Sikh soldier from the BSF, Amar Singh, was their operator. An hour-long programme went on air interspersed with several Bengali patriotic songs.

Since the provisional camp in Bagafa had to shift, this radio station needed a different base. The next stop was Agartala where live programmes were replaced by recorded broadcast. Working for a covert radio service had its own challenges and they generally introduced themselves as BSF employees and also took Hindu names to protect their identities. So, Farooq became Khokan Roy. His co-workers took inspiration in cult Bengali poets and called themselves names like Sunil and Shakti.

To increase listenership, a decision was taken to shift to Kolkata. The station was put under the jurisdiction of the provisional Bangladesh government-in-exile under the prime ministership of Tajuddin Ahmad. One room at the Ballygunge house, which then housed some ministers of Bangladesh government-in-exile, was designated as the studio. “Tajuddin Ahmed was present there when we shifted. We used to sleep on mattresses on the floor,” Farooq recalls.

May 25 was chosen as the day for the first programme from Kolkata to go on air because it coincided with poet Kazi Nazrul Islam’s birthday. Music played a very important role in the Kolkata chapter of broadcast. According to Mamoon, “Besides the songs of Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Atul Prasad Sen, Dwijendralal Ray and Govinda Haldar, lyricists from West Bengal wrote new songs that were played by the Kendra.”

One of the most popular voices was Salil Chowdhury. His daughter Antara remembers her father’s 1971 album called ‘Bangla Amar Bangla’. “Mainly meant for the mukijuddha (or the liberation war), Baba had re-recorded his 40s song called ‘O alor pathojatri’ with Manna De, my mother Sabita Chowdhury and Bombay Youth Choir for this album. Manna uncle had recorded two solo songs with chorus called ‘Manbona bondhone’ and ‘Dhonyo ami jonmechhi’. Singers also got inspiration from his earlier IPTA compositions,” she says.

Whenever she asked him how he wrote such songs of mass awakening, Chowdhury would say it was because he knew the world of grassroot workers. Almost two decades later in 1990, Chowdhury was given the welcome of a mass leader in Dhaka. “Baba was in tears when they lifted him on their shoulders and entered the auditorium. In 2012, my mother and I went to Dhaka when the Bangladesh government posthumously gave him the Muktijuddha Maitreye Samman Award,” she says.

Support from UK/ US popular artistes

Priyanka Dasgupta, Nov 28, 2021: The Times of India

BAEZ TO HARRISON, THEY LENT THEIR VOICE TO THE CAUSE

In 1971, American singer Joan Baez’s sang the haunting ‘Bangladesh Bangladesh/ Bangladesh Bangladesh/When the sun sinks in the west, die million people of the Bangladesh …”. Her lyrics were based on the Pakistani army crackdown on unarmed sleeping Bengali students at Dhaka University on March 25, 1971, which ignited the Liberation War. The lyrics of George Harrison’s ‘Bangla Desh’, which released as a single in July 1971, also touched a raw nerve. Harrison sang: “Although I couldn’t feel the pain/I knew I had to try/ Now I’m asking all of you/ To help us save some lives/ Bangladesh, Bangladesh/ Where so many people are dying fast/ And it sure looks like a mess/I’ve never seen such distress.”

The ‘Concert for Bangladesh’ opened at New York’s Madison Square Garden with Pandit Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Ustad Alla Rakha, Harrison, Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr, Billy Preston and Eric Clapton in performance. The songs and the footage of Bengali refugees moved the world. More than $12 million was raised, and a documentary film was made. “This concert literally gave Bangladesh world recognition,” says Yousuff.

War heroes

The top heroes

Dec 16, 2021: The Times of India

LANCE NAIK ALBERT EKKA (POSTHUMOUS) — PARAM VIR CHAKRA

Ekka belonged to a tribe in Gumla, Jharkhand, and was a skilled hunter. He was at Gangasagar on the Eastern front where Indian troops faced intense shelling and small arms fire on December 3. He charged at an enemy bunker, bayoneted two soldiers and silenced a light machine gun. Although seriously wounded, he continued to clear bunkers. When a medium machine gun opened up from a building, he lobbed a grenade into a bunker, killing a soldier and injuring another. He scaled a wall, entered the bunker and bayoneted a soldier who was still firing. He later succumbed to injuries

2ND LIEUTENANT ARUN KHETARPAL (POSTHUMOUS) — PVC

Commissioned in 17 Poona Horse in June, Khetarpal (21) was at Basantar when Indian troops at Jarpal (Shakargarh sector) were attacked by a Pakistani armoured regiment on December 16. The squadron commander asked for reinforcements and Khetarpal moved in. One of his tank commanders was killed but Khetarpal continued to attack. When enemy tanks started pulling back, he chased and destroyed one. The enemy launched another attack but was held back by 3 tanks, one of which was manned by Khetarpal. In the battle, 10 Pakistani tanks were destroyed, 4 by Khetarpal. But his tank was hit. Khetarpal was wounded and told to abandon it but he continued engaging the enemy. He destroyed a tank before another hit killed him

FLYING OFFICER NIRMAL JIT SINGH SEKHON (POSTHUMOUS) — PVC

Born at Isewal, Ludhiana, Sekhon was a pilot in a Gnat detachment based at Srinagar for the air defence of the Valley.

He and his colleagues fought successive waves of Pakistani aircraft. On December 14, 1971, Srinagar airfield was attacked by Pakistani Sabre. In spite of the danger, Sekhon took off and shot one aircraft and set another on fire. But his Gnat was outnumbered four to one. It crashed and he was killed. The Pakistanis could not cause any more damage to the airfield

COLONEL HOSHIAR SINGH — PVC

Singh’s battalion, 3 Grenadiers, was ordered to establish a bridgehead across the Basantar in Shakargarh on December 15, 1971. After a hand-to-hand fight, his troops captured Jarpal, a well-fortified position. The enemy responded with 3 counter-attacks on December 16, two of them supported by armour. Singh went from trench to trench, encouraging his men to fight. On December 17, the Pakistanis attacked again with heavy artillery support. A shell landed near Singh’s machine gun post injuring many. He rushed to the gun pit and operated the machine gun. The enemy retreated leaving behind 85 dead. Singh, who was severely injured, refused to be evacuated till the ceasefire

PETTY OFFICER CHIMAN SINGH YADAV — MAHA VIR CHAKRA

Seaman Chiman Singh Yadav was one of the personnel tasked with training Mukti Bahini fighters. Between December 8 and 11, 1971, he took part in an offensive in Mongla and Khulna. His boat sank off Khulna and he was wounded, but managed to take two of his party to the shore amid heavy firing. He charged at the enemy, enabling his colleagues to escape, but was taken prisoner himself. He was hospitalised after Bangladesh was liberated

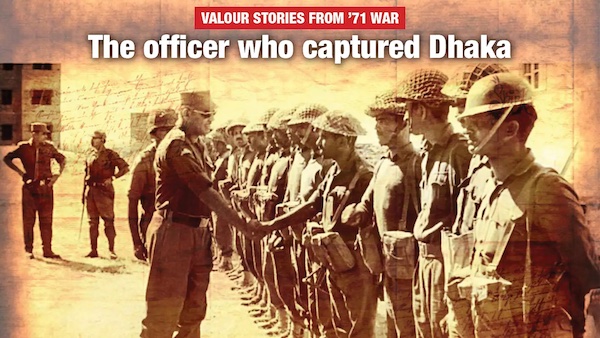

Lt Gen Sagat Singh

Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

From: Parul Kulshrestha, December 23, 2020: The Times of India

Born July 14, 1919 in Bikaner state of the erstwhile Rajputana, Sagat belonged to a family of soldiers. His father fought in World War I from the famous Camel Corps of Bikaner Risala. After passing out from Indian Military Academy in 1941, Sagat took part in World War II from Bikaner State Forces. After Independence, he opted to be part of Indian Army.

When war broke out in Bangladesh, then East Pakistan, Lt General Sagat Singh, commanding 4 Corps, was given the task to advance and capture all the territory to the east of Meghna river. There were three other battalions as well entering from different directions into East Pakistan.

According to military historians, the original plan was to just capture a major portion of East Pakistan. Major General V K Singh in his book ‘Leadership in Indian Army’ mentions that although Dacca (Dhaka) wasn’t spelt out in the instruction given by the Army headquarters, high commands had decided that once every corps achieved its task, the forces would re-group and then launch a combined attack on Dacca from West. After a few days of war, it became clear to Sagat that only capture of Dacca would end the war. His seniors denied him the permission, which Sagat refused to abide by and started planning to enter Dacca. Pakistanis had destroyed the bridge on Meghna river leaving steamers and helicopter only option to move further.

On December 9, 1971, Sagat commandeered many steamers and used his 12 MI-4 helicopters to airlift the troops to helipads that had been marked by torches. The operation lasted 36 hours. Major General Singh wrote that this was one of the first times when an air-bridge was used to cross a major water obstacle by a brigade group.

After a few days, all the corps started advancing towards their goals and on December 14, the first attack on Dacca took place. Unfortunately, Sagat’s brigade wasn’t the first one to enter Dacca city, but the artillery shelling by his men on the nights of December 15 and 16 hastened the surrender of Pakistan and a ceasefire was declared on December 16. After the liberation of Bangladesh, Sagat was given the responsibility to stay in the newly formed country to maintain peace and security. His prime worry was to prevent men of Mukti Bahini groups (freedom fighters of Bangladesh liberation) from taking pot shots on Pakistani army. He had to shift all the higher Pakistani officials to Kolkata in fear of them getting shot by Mukti Bahini boys.

He sent troops to the Dhanmondi area to rescue Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s family to safety. By December 25, peace had returned to Dacca.

Despite good performance in the Bangladesh war, earlier in Operation Vijay capturing Goa in 1961 and his wise decision of holding on to Nathu La post defying his senior’s orders in 1967, Sagat was never given any gallantry award. He was awarded Padma Bhushan later, which is rarely given to soldiers. Sagat retired in 1974 and settled down in Jaipur. On September 26, 2001, he passed away after a prolonged illness.

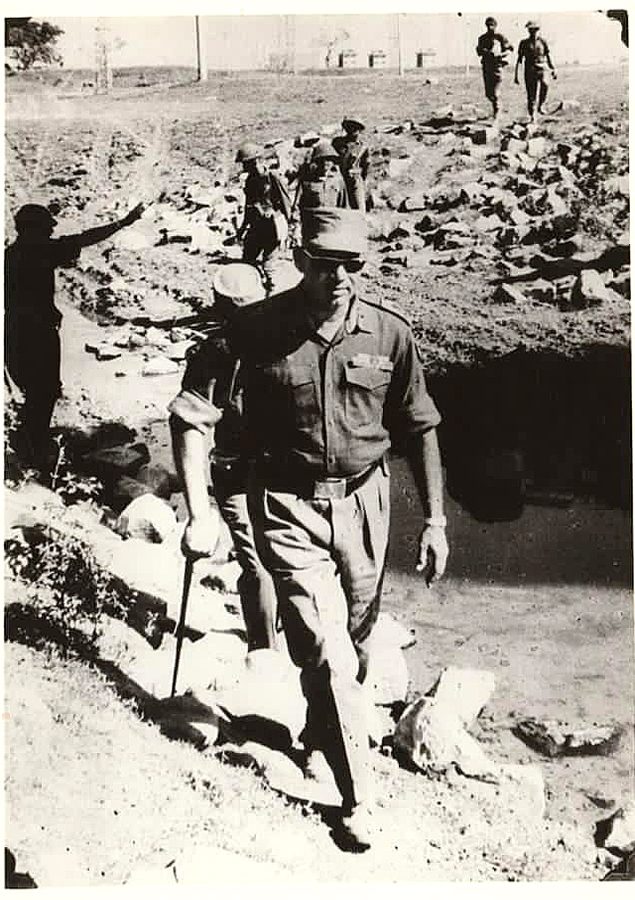

2

Vikram Jit Singh, August 25, 2018: The Times of India

Bullet that played with fate of 1971 war

CHANDIGARH: Had a bullet veered just a few millimetres more, India's offensive to Dhaka over the river Megha may have received a major jolt during the 1971 war. This was when the heroic IV corps commander and Padma Bhushan awardee, the late Lt Gen Sagat Singh, got a bit too daring for his own good and insisted on flying into enemy territory to undertake a recce to locate landing spots for infantry troops to be borne by Mi-4 helicopters. Though the corps commander found one landing spot without trouble, the search for the next one flew into hostile fire with the helicopter receiving quite a few bullets, the pilot a bullet in his upper thigh and another bullet grazing Lt Gen Singh's forehead and piercing through his peak cap.

These incidents and anecdotes of `Op Cactus-Lily' were revealed in a fascinating audio-visual presentation on Tuesday by retired Air Marshal Man Mohan Singh (Vir Chakra), who led the 15 Squadron of Gnats during the War. “Jorhat station commander Group Captain Chandan Singh tried hard to discourage Lt Gen Singh from going for the recce but the latter was insistent. Lt Gen Singh was of the view that the Pakistanis did not have a continuous line of defence on the western side of the Meghna river and there would be gaps where our troops could be landed. So, off he flew with a reluctant Group Captain Chandan for the recce and they had a providential escape. On getting to know of the incident and location of the fire, my squadron scrambled some gnats and we blew up that location and the buildings there with rocket fire,“ Air Marshal Singh told TOI.

Lt Gen Singh, who also was in the vanguard of the 1961liberation of Goa as then commander of the 50 (Independent) Parachute Brigade, certainly was aleader who brooked no `ifs and buts' when it came to operations. “After the troops had landed across the Meghna river, Lt Gen Singh asked the commander of a squadron of PT-76 amphibious tanks to cross the river. The squadron commander pointed out to Lt Gen Singh that the Meghna was 1.5 km wide and subject to intense tides of 8 knots. The PT-76 tanks were meant to cross European rivers, which were as docile as canals.However, Lt Gen Sagat was firm. He told the squadron commander that get the tanks across even if half of them sink. The orders were obeyed and the tanks went across, though a few of them stalled midway and timely help of local river folk helped them to cross safely,“ recounts Air Marshal Singh.

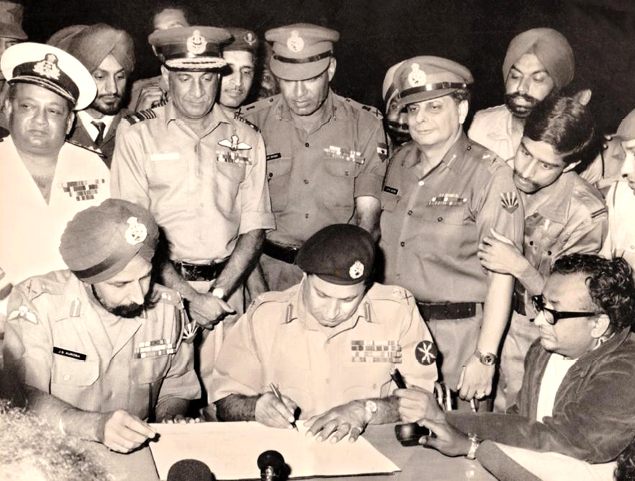

Lt Gen Singh was able to race through to Dhaka by crossing the Meghna using courage and tact. The stage was now set for the mega event of `Surrender at Dhaka', December 16, 1971.“While the photograph of the Eastern Army Commander, Lt Gen Jagjit S Aurora at the surrender ceremony is truly an iconic one, what took everyone by surprise was that Lt Gen Aurora flew in for the ceremony in an Avro aircraft from Kolkata to Agartala with his wife in tow.From Agartala, the couple then took a helicopter to Dhaka for the ceremony . I also flew down to Dhaka for the ceremony with Group Captain Chandan Singh.What took everyone by surprise was the presence of Aurora's wife for wives are not taken into the war zone. I believe the then Army COAS ticked off Lt Gen Aurora for the transgression,“ Air Marshal Singh told TOI.

A memorable encounter at Dhaka was with the Pakistan Air Force's Air Officer Commanding, Dhaka, Inamul Haq, who was a prisoner and later rose to the rank of Air Marshal. “I saluted and introduced myself as the 15 Squadron commander of Gnats and we exchanged due courtsies. He was curious to know which special bombs the Russians had given to the IAF that had so accurately bombed out the PAF runaways at Tezgaon and Kurmila. I told him that the IAF's Squadrons 4 & 28 of MiG 21 FLs had used 'dumb' bombs or free-falling bombs (USSR-made 500 kg, M-62 bombs) but there was nothing special about them. Haq was very impressed with the bombing accuracy and commended the IAF bomber pilots,“ recalled Air Marshal Singh.

Zira, (Ferozepur district): defusing bombs

Dec 15, 2021: The Times of India

From: ==Zira, (Ferozepur district): defusing bombs== Dec 15, 2021: The Times of India

Posted with a bomb disposal unit of the Indian Army in Punjab during the Bangladesh Liberation War, Subedar Sewa Singh, 92 now, narrates how every bomb could not be defused with the right equipment because, often, there wasn’t any. For five of them at a border village, he used his bare hands, saved hundreds and survived

Within days in the winter of 1971, the people of Zira, a small village in Punjab’s Ferozepur district near the India-Pakistan border, had learnt how to identify a bomb — a large metal block with markings of Pakistan’s ordnance factory or those of the UK and US. On December 3, Pakistan had launched an airstrike on India that set off a war and would eventually lead to the creation of Bangladesh. Bombs up to 1,000 pounds were dropped on areas along the India-Pakistan border in Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir. But when seven of these did not go off, Zira descended into panic.

Sewa Singh, a subedar with the Bomb Disposal Platoon of the Bombay Engineers Group, remembers being called in. But they were low on time, resources and intel. Sewa knew he had to act fast. “My unit defused seven bombs, five of which I disarmed with my own hands,” he said — bombs that could have gone off any moment. The village of Zira and the hundreds who called it home were saved.

From a long line of fighters

Sewa is now 92 and lives at Ambala Cantonment with his son, Balwinder. With age, it has become difficult for him to speak, hear and walk. But when the 1971 War comes up, something stirs in his eyes. “I never feared anything. Lives of innocent people were at stake,” he said.

For Sewa, military service just meant carrying on the family tradition. His father Piara Singh was a sepoy with the British Indian Army and his grandfather Gopal Singh was a subedar. Two of his sons have also served with the armed forces — Dilbagh retired as a petty officer and Bhupinder, a diver, died in service at sea.

Sewa was 18 when he joined the Indian Army with the first division in his Army Special training. It was 1947, the year of Independence and Partition, and he was posted at Kirkee in Pune.

He saw action when the 1965 India-Pakistan War broke out, and then again when hostilities broke out between the two countries in 1971.

Why did the bombs not explode?

Sewa said it could be faulty technology or plain mind games. “It could be that the Pakistanis resorted to panic bombing. Sometimes, the bombs were not properly primed. Often, the fuse systems were all wrong,” he explained. “The time factor (when it would go off) was often ignored while dropping them. Besides, many bombs were vintage, from World War II, with worn-out fuses and detonation devices.” The other possibility was psychological warfare. “The Pakistani planes dropped a large number of bombs that were either defective or had time devices attached. They may have been dropped to create panic.”

‘Could have penetrated tanks’

Soon after the chaos unravelled on December 3, he said, this had become a common affair. “Pakistani air force dropped 500-1,000 pound bombs over border areas. Many did not explode,” he added. “But if they had gone off, they could have penetrated tanks.”

Of the seven bombs his unit was called in for, six were at the village of Zira. One had landed on a pile of foodgrain sacks at a Food Corporation of India godown.

Why, though, did Sewa have to defuse them with his hands?

“The fuse in these bombs and its mechanism (were) of a new type, and there was no information regarding the method of neutralising it,” said the citation for the Shaurya Chakra Singh got after the India-Pakistan war ended. “There was no special bomb disposal equipment and stores to immunise the fuses. Undeterred, Subedar Sewa Singh, at grave risk to life and safety, decided to extract the fuse manually.”

He was honoured with the gallantry award on December 24, 1971, a week after the war ended, by then President VV Giri. “My father and my family got a chance to stay at the President’s residence!” he said, shuffling photographs he has with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and defence minister Jagjivan Ram. “I am glad I could help. How does losing one life matter when so many can be saved?”