1947: The partition of India, the human aspect

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

1947: Documenting partition

May 27, 2007

REVIEWS: Documenting partition

Reviewed by Rabab Naqvi

ALMost 60 years after partition, historians are still exploring whether it was inevitable and who was really responsible for it. It is commonly believed that Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah alone was responsible for the partition of India and the formation of Pakistan. K.C. Yadav has put together a collection of old and new writings which provides an alternative perspective. It is also an opportunity to read excerpts from hard-to-get books such as Rammanohar Lohia’s Guilty Men of Partition, Ambedkar’s Pakistan and others.

The main purpose of the book is to project what is known as the revisionist point of view of the events that led to the creation of Pakistan as opposed to the traditionalist approach: ‘Cogress for unity’ and ‘Muslim League for partition’. Running throughout the book is the theme that the division of India was avertable had Cogress leadership and other Hindu groups paid attention to valid Muslim demands. Jinnah’s strategy was to protect the rights of the Muslims within a united India. The arrogance of the Cogress leadership, chauvinism of the Hindu nationalist and the fear of being dominated by upper caste Hindus in free India, pushed Jinnah, although reluctantly, into adopting an intransigent position.

Under the guise of nationalism, Hindu intellectuals and activists advocated a pernicious ideology. Proponents of Pakistan used the two-nation theory but it was the Hindu supremacist Savarkar, founder of the Hindu Mahasabha, who came up with the term. Lala Lajpat Rai considered Hindu-Muslim unity impossible because according to him Islam did not allow for it. Lala Hardayal believed that the future of the Hindu race lay in the Shuddhi (purification) of Muslims.

In recent years, with the opening up of historical documents to the public, the discovery of new facts, the subsiding of emotions, and passing away of personalities directly involved in the independence and partition of India, intellectuals and historians are in a position to analyse the reasons for this momentous decision more critically and objectively. The traditional approach of holding Jinnah and the Muslim League responsible for the formation of Pakistan is too simplistic. This collection of essays demolishes the myth that the making of Pakistan was the doing of one man. It examines the complex political and economic processes, the power struggle, missed opportunities, and complicities that led to the creation of Pakistan.

There are multiple reasons for the division and the Hindu leadership has also come under attack. Rammanohar Lohia writes that the Hindu leadership refused to accept the legitimate demands of the Muslims. In his first hand account of the meeting of the Cogress Working Committee, which accepted the scheme of partition, Lohia is very critical of Nehru and Patel. Lohia writes that Nehru and Patel collaborated with Mountbatten and committed themselves to dividing India without even informing Mahatma Gandhi. “Messrs Nehru and Patel were offensively aggressive to Gandhi at this meeting,” he writes. He is particularly critical of Nehru. He paints Nehru as jealous of Subhas Chandra Bose and a neurotic pro-British.

Unlike Nehru, no one can accuse Jinnah of being in the pocket of the British or question his integrity. B.R. Ambedkar writing on Jinnah says, “It is doubtful if there is a politician in India to whom the adjective incorruptible can be more fitly applied.” Ambedkar also writes that Jinnah “could never be suspected of being a tool in the hands of the British by even the worst of his enemies.” How come that the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, an ardent supporter of united India, a constitutional expert, became the architect of Pakistan? According to Ambedkar, the Hindu-Muslim divide was there in the making for a long time, it just culminated in the creation of Pakistan. “The Hindus and the Muslims have trodden parallel paths … But they never travelled the same path,” he writes.

If opportunities were not mishandled, Hindus and Muslims could have travelled the same paths, says B. Shiva Rao. He was close to some of the processes that led to the division of India in 1947. He offers his personal insight into the lack of foresight and bad judgment on the part of the Cogress leadership that forced the two communities to follow separate paths. Rao’s assertion is that the partition could have been averted and he calls Jinnah “a late and reluctant convert to the scheme for India’s partition”.

Asim Roy also portrays Jinnah as a reluctant convert. He questions some of the myths about Jinnah and the partition embedded in the Indian history books dwelling on the traditionalist approach. He argues that it was the uncompromising attitude of the Cogress and the Hindu chauvinists that led to the demand for Pakistan. In his long and scholarly article, he meticulously goes through the traditionalists’ reasoning and demolishes their assumptions.

V.N. Datta examines the causes for the transformation of both Jinnah and Iqbal from devoted defenders of united India to ardent bidders for a separate state.

No history of partition can be complete without reference to Punjab and Bengal, called the ‘bedrocks’ of partition. Two long chapters separately analyse the situation in each province.

R. Palme Dutt explains British motivation in dividing India and traces the long history of the exploitation of India, and now Pakistan too, at the hands of the British and Americans.

Eight out of the nine essays present a different aspect of the problem and are informative. Some offer a first-hand account of the interplay of situations, processes and personalities. All are analytical and insightful. The article by Margaret Bourke-White seems a little out of place. It has nothing new or enlightening to offer but its inclusion may help sell the book in America.

The book also contains valuable and interesting supplementary material. The section ‘The voices of disunity and division’ includes writings of intellectuals and politicians who propagated Hindu-Muslim differences. In this section it is Lala Hardyal, V.D. Savarkar, Annie Besant and Lala Lajpat Rai that top the list not Jinnah or Iqbal. ‘The Muslim voices for freedom and common destiny’ is a listing of the position of Muslim organisations in favour of united India. Amongst the documents having bearing on the subject is Jinnah’s last will and testament and some letters exchanged between Jinnah and Feroz Khan Noon, just before partition, about the purchase of property by Jinnah in the Hindu-dominated Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh. Feroz Khan Noon himself owned a house in the Kulu Valley of Himachal Pradesh where his wife went to rest after working for the creation of Pakistan.

Jinnah was lucky that the deal did not go through but it also shows how very ignorant the leaders were of the consequences of partition. Jinnah and some others along with him assumed that after partition they would be free to live in any part of India. Nehru is quoted as saying that he did not realise that the judgment of dividing India was irrevocable. He expected partition to be temporary.

The publication should be a worthwhile contribution to the existing literature on partition. It provides the reader not only access to the views of intellectuals, politicians and historians but also to all other pertinent documents that can help common readers and serious researchers delve into the subject deeper without having to dig up each document separately. ________________________________________

India Divided: 1947

Edited by K.C.Yadav

Hope India Publications

415pp. Indian Rs995

“Hidden tales from India's refugee camps”

The Times of India, May 18 2016

Lost Partition tales set to rise from dust

Kim Arora

The letter is dated April 6, 1949. Asif Khwaja from Lahore writes to his friend Amar Kapur, who now lives in Faridabad. There is plenty of catching up. He has joined a newspaper, Khwaja tells his 20-year-old friend, and asks him if he has found a career, too. Their friend Ahmad, he says, has gotten fat and bald. Pained by the Partition, he wants the good old days back. “Rest assured that we on this side will do all in our power to bring laughter and happiness back in our peoples so they may live once again as brothers and golden days return,“ he writes. The letter is one of the over hundred exhibits that will be on display at Partition Museum Project's exhibition in the capital this week.

Called `Rising from the Dust: Hidden Tales from India's 1947 Refugee Camps', the eight-day exhibition at India Habitat Centre starts on Thursday . It will have objects (clothes, utensils, books etc) that people brought along with them as they migrated, photographs, documentary films (silent), archival documents and letters, and artwork, all dating back to 1947.A series of lectures on the Partition from international scholars is also scheduled.The venue will also have camera teams to record interviews of people who have lived through the mass migration and have stories to share. “We have to build an archival record of the largest mass mig ration in history ,“ says Kishwar Desai, who heads the project.

Since the exhibition theme is that of refugee camps, a large focus is on the work of artist Sardari Lal Parasher, which includes sketches and sculptures based on Ambala's Baldev Nagar refugee camp, where Parasher was also the camp commander. Among his sculptures is that of a woman's head, made from the earth of the camp itself.

Desai is currently collec ting material for the museum she aims to set up eventually .“The importance of these objects comes from the fact that they are a part of a lived experience. We need to gather and mine the experience of the Partition,“ says Desai.

She shows TOI a phulkari jacket and a brown leather briefcase. These were among the few things that Bhagwan Singh Maini and Pritam Kaur from Pakistan carried with them before they landed up in the Amritsar refugee camp. The family of the two had spoken of getting them engaged before the families had to flee due to the Partition. “They eventually met waiting in a queue at the refugee camp. They got married soon after that,“ says Desai, who has also collected letters from public and private archives. “There are many letters where people have written to the government about the things or people they have lost.“

There are also newspaper archives with long lists of missing persons with their descriptions. “Strangely , I still haven't come across a single letter where the authorities have written back saying they found something that has been reported missing,“ says Desai, whose own parents made a trip from across the border back in 1947.

Collecting stories of the time can be tricky , say architect Shobha Patpatia and historian Aloka Parasher-Sen, Parasher's daughters. “Our father never spoke to us about the time of the Partition or about the refugee camp. We did not know all this artwork even existed before he passed away (in 1990),“ says Patpatia, who, along with her siblings, has now restored, preserved and exhibited his works in the basement of her south Delhi house.

Parasher was vice-princi pal at Lahore's Mayo School of Art. In India, he set up Government School of Arts in Shimla where the five Parasher siblings spent their childhood. “Daddy and I would go trekking, and then he would talk about these memories if the subject came up. It was never spoken about in detail. He was not preachy , but we knew where the line was drawn,“ recalls Patpatia. “The question is, why did he not talk about it? Because it was too traumatic? Or was it because it was not a part of our lives?“ says Parasher-Sen, pointing out that “a society chooses to remember or forget“.

Part II: After the Partition

The events

The first week after Partition

August 29, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 29, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 29, 2021: The Times of India

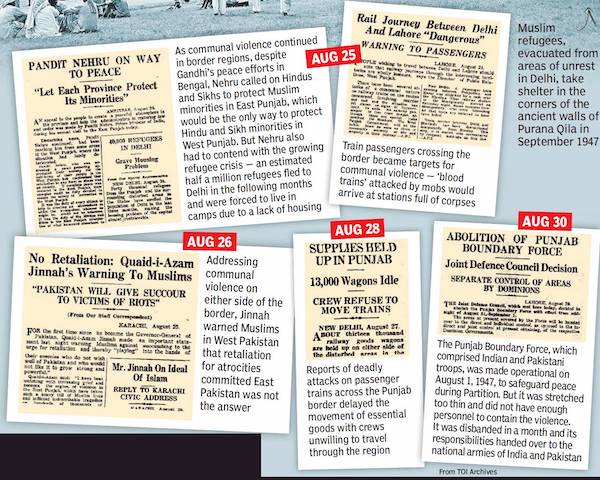

The Indian Independence Act of 1947 freed hundreds of millions of people from British occupation and led to the creation of two new countries. But amid the fanfare came the tragedies of Partition — millions were killed and displaced as Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus migrated en masse across newly drawn borders in the weeks after August 15, 1947.

The original plan for the British to leave India by June 1948 was abruptly brought forward by a year. By mid-1947, it became clear Independence would not result in a united India. The Indo-Pakistan border was drawn along religious lines. But splitting Punjab, the region at the centre of Partition, was no simple task. The ‘Radcliffe Line’ that cleaved the province left significant pockets of Hindu and Sikh populations in Pakistan and Muslim populations in India.

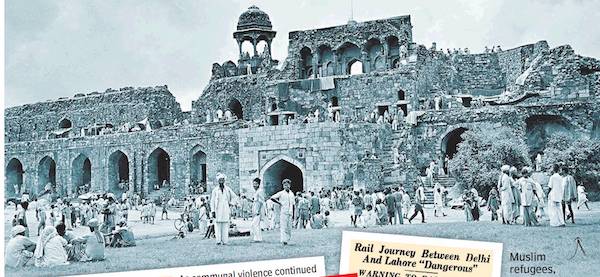

Despite some government efforts to ease the population transfer, the subcontinent’s new leaders were not prepared to prevent the death and displacement that followed. About 1.5 crore people, fearing the implications of becoming religious minorities, were uprooted from their homes on either side of the border, and many of those who stayed put became victims of communal violence. Estimates suggest anywhere between 2 lakh and 30 lakh were killed. In the week that followed the boundary award announcement on August 18, coverage in the Times of India documented how Partition unfolded.