Atal Bihari Vajpayee

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A profile

The BJP's first truly mass leader is officially etched as a national symbol, making him a role model for India's right-wing and beyond

Ravish Tiwari December 25, 2014

Thanksgiving is not a tradition on the Indian calendar. And it is unlikely the thought would have crossed the mind of the powers that be in NDA 2 who went through with the not-unexpected decision to confer the Bharat Ratna on Atal Bihari Vajpayee-former prime minister, poet, patriarch and a political pioneer like few others. Call it coincidence, or the articulation of a subconscious thought, but there is little doubt that NDA 2 owes a huge debt of gratitude to the man who was not just the architect of NDA 1 but also the moderate face of India's right wing politics.

A face, thought and expression- through lucid prose, poetry and some very pregnant pauses-that helped build a mainstream right-wing political movement and made it acceptable to the masses. So much so that his six-year reign at the head of NDA 1, and the decades of struggle preceding that, is now seen as the foundation on which NDA 2, India's first genuinely right-wing government with a brute majority of its own, has been built. The timing, therefore, could not be more apt.

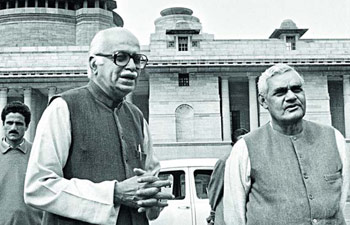

Vajpayee was not alone when the seeds of an alternative, Hindu nationalist political thought were being sown across India. Former Hindu Mahasabha leader Syama Prasad Mookerjee had quit Jawaharlal Nehru's cabinet to float the Jan Sangh had provided some of its finest men- Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay, Nanaji Deshmukh, Jagannath Rao Joshi, Kushabhau Thakre and Sunder Singh Bhandari, among others-to help this political alternative grow roots. Vajpayee and L.K. Advani were the electoral faces identified to push the movement. The Jan Sangh mutated into the Janata Party before reclaiming itself as the BJP, struggled to cope with the untimely deaths of Mookerjee and Upadhyay and the fact that others such as Deshmukh, Joshi, Thakre and Bhandari had little appeal beyond their own party. Enter Vajpayee, the powerful orator, moderate nationalist, bon vivant and relationship builder. The India of the 1980s and '90s, where political churn met economic flexibility and sought to discard socialist shibboleths was a platform that was made to order. Although Advani also climbed dizzying heights of popular appeal at the peak of the Ram Temple campaign, he will happily concede that his fellow traveller's mass appeal was more enduring. While the Hindu nationalist movement has a new icon in the form of Narendra Modi, it will take him some doing to overshadow or dislodge Vajpayee as the presiding deity. Debating against Nehru, supporting Indira Gandhi for the 1971 Bangaldesh war, opposing her imposition of Emergency, merging their carefully nurtured Jan Sangh into the Janata Party, floating the BJP, supporting V.P. Singh to dislodge Congress again and becoming the first BJP prime minister in 1996-Vajpayee has been the flagbearer at all key political milestones in post-Independence India. It's a feat that can be matched by few other anti-Congress icons.

Vajpayee's NDA with an alphabet soup of some two dozen parties is arguably India's best-run coalition government yet. It sought to unshackle the economy while trying to keep the saffron warriors at bay-a worthy role model for its successor. And that is perhaps where the irony also comes into play-a Modi trying to focus on governance and development while the Sangh snaps at his heels with its divisive agenda. The wheel comes a full circle. Not only is the Bharat Ratna a token of the subconscious gratitude, it is also a mark of recognition for the BJP's ideal role model.

Political career

Shekhar Gupta

March 26, 2015

The man who got it right: Poet, pragmatist, always political

Atal Bihari Vajpayee's greatest, durable legacy is to show that India is best governed with a large heart

Shekhar Gupta

The Narendra Modi government has given us the perfect reason to do so by honouring Atal Bihari Vajpayee with the Bharat Ratna. One key assessment for a full-term prime minister, particularly a popularly elected one, would be how much of what he willed, began and believed in survive his departure. On that, Vajpayee scores very well indeed.

There's been broad continuity in the direction of India's economic and foreign policy. A leader, therefore, can only change the pace and width. But this isn't a big, substantive change in mindsets, a big idea that challenges ossified ones and is established so firmly that it is unassailable to future depredations. Nehru's liberal pluralism is one such idea.

Even Modi has to swear by it, even if he prefers to do so in the name of Patel and Gandhi. His second contribution-a rational, questioning, secular society with scientific temper-has sustained so far. But it will be tested in the coming years as India's new politics probes an important fault line there: contradiction between his nearly godless view of secularism and a deeply god-fearing society. The third one, socialism, Nehruvian or Fabian, has been fully demolished, notably for 15 years by Nehru's own party's governments (under P.V. Narasimha Rao, Manmohan Singh). Ditto for Indira Gandhi. Her idea of a powerful, no-nonsense India not shy of playing Great Power politics endures, and will be strengthened as the BJP reaches out to get in their creeping acquisition of Congress icons after Madan Mohan Malaviya, Sardar Patel, and now Lal Bahadur Shastri. Her aggressive equal-distribution-of-poverty in the name of Garibi Hatao is now dead and buried, and derided as povertarianism. If her party's score of 44 in 2014 is the coffin, legislations amending coal and mineral laws and states loosening labour regulations are the last nails in it.

Now the unusual suspect, Rao. The demolition of two of the three ideological pillars of the Nehru-Indira era, statist socialism and Westophobic worldview, began in his five years. He was a socialist but more a pragmatist. He was helped greatly by the seven-year eclipse of the Gandhi family, directly for five years through his prime ministership and for his new ideas through the Gowda-Gujral period, when a coalition backed by the Congress left its economy to P. Chidambaram, then of the breakaway Tamil Maanila Congress. No matter how deep the Congress may bury his name in their party history, Rao won that intellectual battle, and you can never take away from his five difficult years.

Vajpayee followed in his wake (after the short-lived United Front) to become the first non-Congress leader to get five, in fact six, years of prime ministership, with one hiccup when he was defeated in the Lok Sabha in 1999 and forced to fight yet another election, his third in three years. Both were veterans of Parliament and had a great deal of mutual respect and admiration between them. Vajpayee always saw Rao as an experienced, wise patriot, and did not have the same suspicions of him as of the Dynasty. Rao saw Vajpayee as an alter ego of sorts, in spite of such a contrast in their personalities. Remember, he sent him to Geneva as leader of the Indian delegation to counter a threatened UN Human Rights Commission vote against India, with Salman Khurshid, then MoS for external affairs, as his deputy. He never detested Vajpayee personally or ideologically. That "honour" was reserved for Advani. I, therefore, firmly believe the story that as Rao handed over to Vajpayee (although initially only for 13 days), he told him that he had kept all "saamagri" (material, nuclear) ready, and Vajpayee should go ahead and test once he had the mandate. The departure Rao bravely made from the Nehru-Indira construct on foreign and economic policies has sustained.

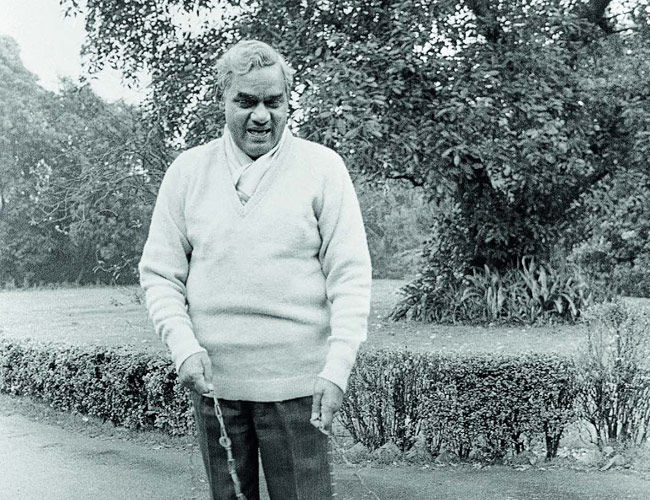

What exactly was Vajpayee's opportunity once the direction of foreign and economic policies was set? A liberal constitutionalist and a romantic, a bit like Nehru, and a poet too. Not gifted with the ruthlessness of an Indira, a Rao or now Modi, nor a visionary like Nehru. But he had a great, instinctive mind and a wonderfully warm and, more important, large heart. God never designed a man withall the key attributes of leadership. The greatest leaders in history have some and lack a few. But nobody ever did, or will, become a great leader in any field without a big heart. On that test, Vajpayee ranks very much at the top. We leave Manmohan Singh out of this as he really wasn't a fully empowered leader.

Nor was Vajpayee when sworn in prime minister for the first time in 1996 by virtue of being the leader of the largest single party/coalition. He knew he was going to fail his first test, the vote of confidence in Parliament within days, as all of the opposition was against him under the secular umbrella. But his mind was made up and his heart was ready to chalk the course that would ensure for him such a special place in our history.

It was two days before he was to speak in that debate that I got a call to see him in his old Raisina Road home, which he had not moved from, knowing his tenure was short. He was calm, determined, even smiling. "I believe you once wrote somewhere that the majority in India had acquired a minority complex?" he asked. I said yes; it was in a monograph I wrote for the International Institute of Strategic Studies, London (India Redefines its Role, OUP, 1995) while on a sabbatical from this magazine. He engaged in a short debate on why Hindus in India felt vulnerable, even persecuted, despite being in an overwhelming majority. He said he understood why, but did not fully agree with it. In any case, he said, he was elected prime minister not to feel sorry for the Hindus, but to lead them out of that hole and also reassure the minorities. He dwelt on that majority-getting-the-minority-complex idea in his emotional speech facing a confirmed defeat.

But in that defeat he had told India's Parliament and its people that he was different from the usual BJP stereotype. That trust ensured two things. One, that a lot more people, besides the BJP's committed voters, were willing to check him out now. And two, many smaller parties sitting on the secular fence found the reassurance to cross over to the NDA. Remember, Nitish, Mamata, Naveen Patnaik, even Omar Abdullah of the National Conference were in his councilof ministers.

In his six years, he established two new ideas in Indian politics. One, that the BJP could lead a centre-right government in India entirely within the classical framework of the Constitution, thereby confirming the idea that India would change BJP more than BJP change India. Two, that the doctrine of strategic restraint would hold, even under grave provocation, as in Kargil and the attack on Parliament. The gains were evident: the first established the sanctity of the LoC and the second globally confirmed Pakistan's status as a terror-exporting nation.

The second postulate will be tested in the coming years. But the first, the Vajpayee definition of Rajdharma for the BJP, has been established. If Modi now swears by Vajpayee rather than Golwalkar, the direction he set for the BJP, or the governing ideology of the Indian Right, will sustain. That will be his lasting contribution, and it is as formidable as Nehru's liberalism, Indira's strength and Rao's pragmatism. On that scale, Vajpayee will rank right up there. Never mind the irony of his being conferred the Bharat Ratna by Modi's government.