Sahir Ludhianvi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

His continuing relevance

Nasreen Munni Kabir, March 8, 2022: The Times of India

March 8, 2021 marked the 100th birth anniversary of Sahir Ludhianvi, the extraordinary Urdu poet-lyricist, born in 1921. The diary, In the Year of Sahir, is my attempt to celebrate this amazingly gifted man.

A wealth of articles, two biographies in English and a formidable publication in Urdu ( Fann aur Shaksiyat) by the poet Sabir Dutt already exist on Sahir, not to forget the extensive blogs and websites dedicated to him, plus there are several editions of his poetry collections, which are continuously reprinted.

In Surinder Deol’s biography, A Literary Portrait, he informs us that Sahir’s Talkhiyan is the only other Urdu poetry book, besides Deewan-e-Ghalib, to have been published in many Hindi and Urdu editions. So, the question for me was to seek out a different way of presenting new insights into his work and personality that could be of historical value and fresh and engaging.

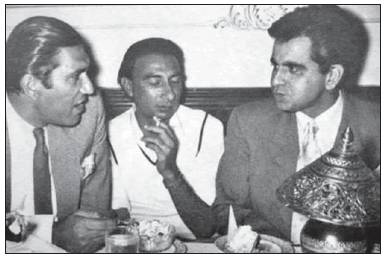

Following on from the cinema diary I produced in 2013, which celebrated 100 years of Indian cinema, the concept of another diary seemed both appropriate and appealing; the idea was to present observations and memories from an array of contributors, interspersed with unseen and wonderful photographs of Sahir from the collection of Meesam Raza, a dedicated admirer of the poet. With this in mind, I went about contacting more than 30 people — poets, singers, directors, producers, distributors, writers, academics, musicians, screenwriters, playwrights, actors, artists and theatre directors — all of whom generously gave of their time to share their experiences of working with Sahir or living with his songs and poems.

Gradually the diary took shape as one by one the contributors sent me their comments, each telling a unique story.

Asha Bhosle remembers the day she recorded the amazing Aage Bhi Jaane Na Tu… from Waqt: “As I sat rehearsing the song in Mumbai’s Famous Tardeo Recording Centre, I heard the familiar soft voice greeting me. I looked up to see a tall lanky figure dressed in his familiar white cotton shirt, dark trousers and open sandals. I complimented him on the lyrics of the song and mentioned that the meaning resembled the essence of the Bhagwad Gita. He acknowledged it with a smile and complimented me on my white sari, which had a bright border… During the recording of Woh Subah Kabhi toh Aayegi, he jokingly remarked to music director Khayyam that his career’s ‘subah’ had dawned with this song.”

Ramesh Sippy recalls a time when he was eight years old, sitting in the corner of a room, when Sahir came to the family house to discuss a song with his father, G P Sippy. “Sahir sahib proceeded to recite the song words: Ab vo karam kare ya sitam main nashe mein hun. Mujhko na koi hosh na ghum main nashe mein hoon. [Whether she’s kind or cruel, I am drunk. Unmindful of joy or sorrow, I am drunk]. My father liked the lyrics very much and wanted it for Marine Drive, but Sahir sahib refused point blank. He was offered double the money, but the answer was still a ‘no’. My father was a known teetotaler, so Sahir sahib explained: ‘How can I give this song to a man who doesn’t even drink alcohol!’ That evening my father poured himself his first drink. And the song was his.”

Then there is the gifted musician Zakir Hussain, who observed Sahir’s approach to the required metre (wording the melody) is similar to that of a sitar or sarod player. As Zakir Hussain explains: “It’s how a tabla player instantaneously organises and reorganises rhythm patterns to aesthetically express the feeling of the piece. The example that comes to mind are the lyrics of Abhi naa jao chod kar. His use of the word ‘ zara’ is amazing. He uses it at the beginning of the line and suddenly switches it to the end of the following line; this I find masterful.” Each comment and observation brings a new understanding of Sahir’s approach to songwriting — and then there is his formidable mastery of Urdu poetry. I think the proudest moment for me, when putting the diary together, was being able to track down and include K A Abbas’ long-forgotten translation of Parchhaiyan, a very fine work, first published in 1958 under the title Shadows Speak, a book that is now out of print.

The idea of tracing the journey of this masterful moving anti-war poem by Sahir and including a photograph of the book’s original cloth cover was most rewarding. This was possible thanks to Gulzar sahib, who has had a signed copy of the first edition in his library.

In essence, this diary is not a history of Sahir but a personal tribute to a poet whose work is so impressive and enduring in its vast range and appeal. The only complaint I have heard so far about In the Year of Sahir is from friends who say that although this is a diary, they do not want to write in it. My answer is that a diary is also about marking time, and as far as the writing is concerned, who can compete with Sahir’s words?

Gulzar’s tribute

By Gulzar, March 8, 2021: The Times of India

From: By Gulzar, March 8, 2021: The Times of India

Sahirsaab made his presence felt as much in films as in literature. Anyone who read or listened to Urdu poetry or mushairas in those days would know who Sahir Ludhianvi was. He was a tall, fair, handsome man with small pock marks on his face and a distinct style of speaking. Always very humble, never boastful — because poets sometimes can be very boastful about what they’ve read and what they write — but he was a modest man.

I remember that he was never allowed to leave the stage without reciting his famous poem on the Taj Mahal — ‘Meri mehboob kahi aur mila kar mujhse’ — it was very, very popular with the people. Progressive writers and poets would often argue that it wasn’t fair to look at the Taj Mahal from the lens of the rich against the poor. But Sahirsaab was a committed communist poet and part of the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) like Shailendra and (Ali) Sardar Jafri.

It was a movement that I became involved with later, also. I hadn’t joined films then. I used to work in a motor garage, and attend PWA meetings. But I was lucky to be living in the outhouse of the bungalow where Sahirsaab lived on the first floor. It was called the Coover Lodge at Seven Bungalows, Andheri. On the ground floor lived the famous Urdu writer Krishan Chander, who too, was a legend in his own time. And in the outhouses of that bungalow, three or four strugglers like Ratan Bhattacharya and myself, lived. The compound still exists, although a building has come up now.

When Sahirsaab joined films, he had his own style of using Urdu words that we had never heard of before. For example, the song ‘Yeh raat yeh chandni phir kahaan’ from the movie Jaal. The kind of imagery in phrases like ‘Aur thodi der mein thak ke laut jaayegi’ was very rare at the time. Or take ‘Chalo ek baar phir se ajnabi ban jayein hum dono’ from Gumrah. No other poet until then had expressed separation in a manner that continues to linger in you when you hear it today, just like it did when it was written back then. One could clearly see the individuality in his expressions.

But this modest and humble man also had his own ego and arrogance. He would ask for the same price as the music director of a film. It’s not that he wanted to work with only big names. He’d say, ‘if you can’t afford it then give me a smaller music director, I don’t mind’. That’s how music directors like N Dutta and Ravi went on to compose for him. Sahirsaab was very confident of his poetry.

He is ‘the’ person who called for a strike by writers asking them to not give songs to Vividh Bharti unless they mentioned the name of the writer on their shows. Otherwise, traditionally Vividh Bharti would announce only the names of the singer and composer of a song. Sahirsaab was the man to protest against this and the strike eventually came to an end after Vividh Bharti agreed.

Other than his writing, this was the hallmark of his contributions towards the prestige and identity of writers and poets in the film industry. It has relevance till this date and a cause that Javedsaab (Akhtar) still pursues in his battle for copyright, something that Sahir Ludhianvi did in his time. Javedsaab is someone who he loved very much because his father Jan Nisar Akhtar was a very close friend of Sahir Ludhianvi’s and Javed almost grew up in his house. He was also the first lyricist I ever saw, who had a car. He was like a nawab! In fact, he was the son of a nawab. The only other persons who lived with him in that house were his mother (Sardar Begum) and Ram Prakash Ashq, a very close friend of his who came with him from Pakistan. His mother was a strict lady. Always dressed in white Lucknowi embroidered salwar-kurta she would love him and rebuke him like a child... Bahut daat-ti thi, poore bungaley mein unki awaaz sunai deti thi!

(As told to Mohua Das)

Sudha Malhotra reminisces

Bella Jaisinghani, March 8, 2021: The Times of India

From: Bella Jaisinghani, March 8, 2021: The Times of India

Privileged to have sung his lyrics, says muse

Playback singer Sudha Malhotra was in her twenties when she became an unwitting muse for poet lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi. He recommended her name to film makers and composers, sparking a career that led to songs like ‘Yeh ishq ishq hai’, ‘Na main dhan chahoon’ and ‘Kashti ka khamosh safar hai’. Sudhaji’s personal favourite is ‘Tum mujhe bhool bhi jao’ which she also composed at his instance, reports Bella Jaisinghani.

She said, “All artists, poets, painters need someone to inspire them. If I became an inspiration for somebody, what could I do. I was so young. People can say anything. M F Husain was inspired by Madhuri Dixit. What can anybody do? Our worlds were entirely different.” “I feel I was very fortunate and privileged to have sung Sahir Sahab’s beautiful lyrics. All the songs that he wrote and I sang became such hits. I sang in films for a short time but got so many hits. Sahir Ludhianvi was undoubtedly the greatest poet in my life.”

“Do you know, it was Geeta Dutt and I who originally sang ‘Kabhi Kabhi mere dil mein’ for a Chetan Anand film in 1959-60. It got shelved and I don’t even have a recording. Khayyam Sahab’s tune was nearly the same as the one that was released later.

“The last song I sang by Sahir was ‘Tum mujhe bhool bhi jao toh yeh haq hai tumko’ (Didi). He in fact requested me to craft the tune for it as well, and I did. It helped prove that I was also capable of composition.”

“I often get asked why I gave up such a promising career at the peak. Well, I did. I was getting married at the time. I come from a family of senior government officials. Ab kya kar sakte hain. I say don’t look back.”

“As I said, God has been extremely kind to me that I got a chance to sing Sahir Ludhianvi Sahab’s songs. He was the best, best, best.”