1971 war: From its origins to Dec 1971

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A timeline

December 1971

Man Aman Singh Chhina, Jan 4, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Dec 16, 2021: The Times of India

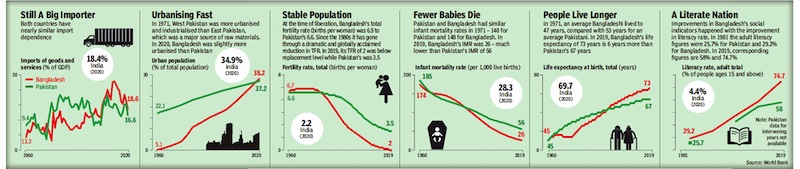

See graphic:

1971 war: From its origins to Dec 1971

A day-to-day account, from December 3-16, of the 1971 India-Pakistan war. East Pakistan seceded from then Pakistan dominion and was declared the People's Republic of Bangladesh, with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as its first prime minister

December 3: Pakistan Air Force launches air strikes against Indian airfields in the Western Sector, including Amritsar, Pathankot, Srinagar, Avantipura, Ambala, Sirsa, Halwara, Agra

December 3 to 6: Indian Air Force retaliates by attacking Pakistan air bases in Western and Eastern sectors. Pakistan attacks Indian ground positions in Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir

December 4: Battle of Longewala takes place in Rajasthan where Pakistani advance towards Jaisalmer is thwarted

December 5: Battle of Ghazipur in East Pakistan. Battle of Basantar in Western sector in Pakistan’s Punjab in the Shakargarh salient near Sialkot. Battle of Dera Baba Nanak in Gurdaspur district of Punjab

December 6: India formally recognises Bangladesh as an independent nation. City of Jessore is liberated

December 7: Battle of Sylhet and Moulovi Bazaar begins in Bangladesh

December 8: Indian Navy launches attack on the Pakistani port city of Karachi

December 9: Indian Army fights Battle of Kushtia in Bangladesh. Chandpur and Daudkandi liberated. A helicopter bridge airlifts Indian troops across Meghna river and makes the fall of Dhaka a matter of time

December 10: Chittagong air base in Bangladesh attacked by Indian Air Force aircraft

December 11: Tangail airdrop of a Parachute Battalion to cut off retreating Pakistani troops in Bangladesh

December 12 to 16: Indian forces push through to Dhaka and enter the city. Pakistan Eastern Command Commander Lt Gen AAK Niazi signs the instrument of surrender and capitulates to Indian Eastern Commander Lt Gen Jagjit Singh Aurora. As many as 93,000 Pakistani troops lay down their arms in Bangladesh

November 21

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

India began the war, not Pakistan. It started with a multi-pronged invasion of East Pakistan on November 21, assisted by the Mukti Bahini (Bangladeshi rebels trained and armed by India). India planned the invasion date to coincide with Id, to help catch the Pakistan army by surprise. The Indian government rejected Pakistani complaints that an invasion had begun and said there were merely ongoing border clashes. But foreign correspondents like the New York Times’ Sydney Schanberg sent on-the-spot reports of Indian troops entering across a wide swath. The Economist, London, said it would now be a race between UN Security Council intervention and a Pakistani counter-attack in the West. India had that summer signed a quasi-defence treaty with the USSR, which vetoed any intervention by the UN Security Council. To raise the stakes and increase chances of US intervention, Pakistan counter-attacked by bombing Indian targets in the West on December 3.

Ultimately it was a 26-day war and not a 13-day one. Pakistan did not start the war and had no motive to do so — it knew it was hopelessly outnumbered in the East and India would have complete military control of the skies. But India had every motive for a war that would give India a friend rather than foe in the East. Detaching Bangladesh from Pakistan meant India would never again have to fight a two-front war against Pakistan. It also meant China could no longer threaten to militarily link up with East Pakistan by capturing the “chicken’s neck” region that connects West Bengal with Assam. Of course, Indian justified its invasion in high moral terms, as the liberation of a territory devastated by Pakistan army genocide, and to facilitate the return of 10 million refugees who had fled to India.

In March 1971, Pakistan arrested Mujibur Rahman, head of the Awami League, for attempting secession. On hearing of this Mujib’s followers led by Tajuddin Ahmad, who had earlier been ambiguous on secession, declared independence and set up a Provisional Government of Bangladesh at the small town of Chuadanga. The only rationale for choosing Chuadanga was that it was far from Dhaka and close to the Indian border and so they could hope, with Indian assistance, to resist for a long time. Meanwhile the Mukti Bahini and rebel Bangladeshi forces attempted, mostly in vain, to combat the Pakistan army advance.

My assignment in The Times of India was to do a daily column titled ‘Gains and Losses’ summing up the military and political events across East Pakistan. I was instructed to play up all positive stories of heroic Bangladeshi resistance and play down reports of Pakistani advances. The newspaper made no pretence of independence or impartiality: it saw itself as a patriotic propaganda tool. However, the advance of the Pakistan army was so swift that the pretence could not be kept up for long. A sad day quickly came when the Bangladesh Provisional Government had to flee from Chuadanga to India. Naturally, I led my column with that news, but was told to relegate that low down. Instead, I was told to lead with a story of a Mukti Bahini attack on a power station in Ashuganj. I could not see how this helped the Bangladeshi cause, but then patriotism is never very logical.

Tajuddin Ahmad and his provisional government started functioning from Kolkata. But for propaganda purposes the Indian government decided to create a fictional town called Mujibnagar, inside the Bangladesh border, from where the Provisional Government led the resistance. This was supposed to somehow confer greater credibility on Tajuddin. But why? In World War II, governments-in-exile of Poland and France operated from London with no loss of credibility.

Dozens of Indian newspapers descended on Mujibnagar to take photos of and have interviews with Tajuddin Ahmad and his colleagues. No newspaper denounced or questioned the wisdom of the fiction. After all, the outcome was clearly going to be determined by Indian military action. Whether the Provisional Government was located in Kolkata or Mujibnagar could make no difference. But in the patriotic zeal of those days, as that army man said, it was given to some to die for the country and others to lie for it.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in jail: Mar 71-Jan 72

A grave for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Dec 21, 2021: The Times of India

Mohanlal Bhaskar was being held in Mianwali jail in Pakistan when Sheikh Mujibur Rehman was brought there in a chopper. A few days later, a jail official picked Bhaskar and seven other Indian inmates to dig a ditch in the block where Sheikh Mujib had a cell. The instructions were specific – the ditch should be eight feet in length and four feet in width and depth. An excerpt from Mohanlal Bhaskar’s book ‘I was India’s spy in Pakistan’

Winter was still tiptoeing in when a chopper alighted inside the prison’s compound. The next morning, we learnt that Sheikh Mujibur Rehman had been brought in from the Lyallpur prison. We also learnt that at the Lyallpur jail, some soldiers belonging to the East Bengal Regiment had attempted to smuggle him out through a secretly-dug tunnel. He was lodged in Mianwali prison’s women inmates’ block. The women inmates were shifted to another barrack. The women inmates’ block lay at the back of barrack number 10.

We, the Indian inmates of the jail, had been shifted to barrack number 10 just days ago. Sheikh Mujibur Rehman was kept amid strict, round-the-clock surveillance by guards from a Pakistani army contingent. His cook prepared his meals, comprising mostly rice and fish.

The next day, when it was confirmed that Sheikh Mujib was in the jail, the Pathans among the prisoners scaled the barracks’ roofs and let out a torrent of filthy abuses aimed at his mother and sisters and threw torn shoes and stones at the women inmates’ block. A few guards got hit with the torn shoes and rocks. The guards subsequently scaled the barracks’ roofs and fired bullets in the air, six shots, to scare the troublemakers who thereafter climbed down. The Pathans, however, continued abusing Sheikh Mujib from their barracks.

Later, the jail’s chief, Chaudhary Naseer, undertook a round of the prison and passed on a message to the inmates – ‘You all must chill. Sheikh Mujib has been brought here to be hanged.’ The clarification sent a wave of jubilation through the jail with the Pakistani inmates breaking into chants of ‘Ya Ali’, ‘Ya Ali’.

We, the Indian inmates, craved a glimpse of Sheikh Mujib. But that was impossible. Yet, the heart yearned to see the ‘Bengal Lion’, who had managed to awaken his people against tyranny and exploitation. He had sacrificed his own family in doing so. As per reports, Sheikh Mujib’s son was shot dead when the latter was being taken into custody. Only his daughter, Sheikh Hasina [Bangladesh’s current prime minister], survived.

We once met his cook in the jail’s storeroom, where one went to collect the ration. The cook was there to pick up the ration meant for Sheikh Mujib. We could not speak to him in the presence of guards. The store’s clerk, however, could not resist a dig: “So, how is the traitor Mujib doing?’ The cook was a tough nut. He responded: “Sheikh Saheb is perfectly fine and healthy and in a good mental space. He keeps saying that he will continue to fight for the rights of the Bengalis till his last breath.”

One day, one of the prison’s senior officials, Fazaldad, arrived at our barrack with a warden in tow and ordered his junior to pick eight Indian prisoners. There was no word about what task we were being assigned. When we were led to the women’s block, where Sheikh Mujib had been lodged, we thought finally we would get a glimpse of the great man. But we found all the windows in the block had been shuttered with wooden screens.

Fazaldad ordered us to dig a ditch – eight feet in length and four feet in width and depth. We deduced instantly that Sheikh Mujib would be hanged and that we were digging his grave. We got on with the job. None of us had the guts to ask Fazaldad what the ditch was for.

No Pakistani inmate was involved in the digging. The jail officials probably thought that the news would be leaked if Pakistanis in the jail got a whiff. By late evening, we had finished the task. Then the wait began, our ears straining for any sound from the gallows.

But nothing happened that night. It seemed the hanging had been postponed. The next morning, when the wards were thrown open, some were saying that the Sheikh was still alive while others claimed he was killed with a poison injection then buried in the grave we had dug last night. But these were all speculations.

Later in the day, when we reached the storeroom to collect our share of jaggery and chana, Sheikh Mujib’s cook was there to collect for him tea leaves, milk and sugar. That was a clear indication that Sheikh Mujib was alive. We later learnt that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had met Pakistan’s President Yahya Khan to ask him to stop the execution. The logic he [Bhutto] had given was that if Sheikh Mujib was hanged, the Bengalis’ anger would burn and destroy the entire rank and file of the Pakistani armed forces stationed in East Pakistan.

The next evening, we were again brought out of our wards and asked to fill up the ditch. We were happy that we had been spared of becoming a part of such a dubious event. But a fortnight later, we were again taken out of our cells and asked to dig a new grave. On this occasion too, Sheikh Mujib was not hanged. And this routine was repeated twice again and each time we were asked the next morning to fill the ditch up.

This is how Sheikh Mujib spent his four months of incarceration at Mianwali prison’s women’s inmates’ block – awaiting to be executed any day, any hour.

When Bangladesh came into being eventually, Sheikh Mujib became its first President. But none would have imagined that the people for whom he had sacrificed everything, including his family, would assassinate him.

A few months before President Mujib was killed, R&AW had got intel of the plot. When the plan for the assassination was being prepared at a secret meeting attended by Bangladeshi army officers, one of the participants there was our mole. He subsequently scribbled a note on the deliberations on a slip of paper and dumped it in a waste bin. An agent of ours later picked up the note.

R&AW’s chief R N Kao posed as a betel-leaf seller to slip into Bangladesh. He met Sheikh Mujib and alerted him about the plot. Sheikh Mujib laughed saying: “How is that possible? They are my sons, they cannot murder me.”

Mujibur Rehman was assassinated at the behest of Bangladesh army’s chief Ziaur Rahman. I go down the memory lane even today, reminiscing about those days when Sheikh Mujib had been imprisoned at the Mianwali prison. Ropes for hanging him had been prepared, graves were dug up. His enemies could not kill him. However, it was his own who assassinated him.

Translated by Abhishek Saran. This memoir, published by Rajkamal Prakashan, won the prestigious Shrikant Verma Award in 1989

Note: Mohanlal Bhaskar was repatriated to India in 1974. He passed away in 2004

[Mohanlal Bhaskar’s account of the events inside Mianwali jail was confirmed by Sheikh Mujibur Rehman himself weeks after he returned to East Pakistan and was elected prime minister of Bangladesh. This is what he told a group of journalists from the US, this NYT story reports:

At 4am, two hours before the killing was to take place, Sheik Mujib related, the prison superintendent, who was friendly to him, opened his cell. “Are you taking me to hang me?” asked Sheik Mujib, who had watched prison employees dig a grave in the compound outside his cell (they said it was a trench for his protection in the event of Indian air raids.) The superintendent, who was greatly excited, assured the prisoner that he was not taking him for hanging.

Sheik Mujib was still dubious. “I told him, ‘If you're going to execute me, then please give me a few minutes to say my last prayers.’”

“No, no, there's no time!” said the superintendent, pulling at Sheik Mujib. “You must come with me quickly!”]

The diplomatic front

Chandrashekhar Dasgupta’s research

Shubhajit Roy, Dec 16, 2021: The Times of India

As a young diplomat, Chandrashekhar Dasgupta was sent to newly-liberated Bangladesh in 1972, and he lived and worked at the Indian High Commission in Dhaka for two years. On the occasion of 50 years of the birth of Bangladesh, Dasgupta has published India and the Bangladesh Liberation War: The Definitive Story (Juggernaut), based on years of research into the P N Haksar papers, the T N Kaul papers, and files and records in the Ministry of External Affairs.

The book offers a comprehensive view of the political, military, and diplomatic strategy adopted by the Indian government during one of the biggest challenges it has faced in the last seven decades — to turn a monumental crisis into an unparalleled opportunity.

Decision to intervene

It was not until March end-early April in 1971 that “the Indian government decided to intervene in the liberation struggle to bring it to an early conclusion”, Dasgupta, now 81, and who went on to become India’s ambassador to China and the European Union, recounted.

“I cite in my book an extremely prescient 1969 R&AW report, which noted the strength of popular feelings. It said this was going to get out of hand and the military was going to be brought in to crush the movement. At that time (1969), the East Bengal rifles would take up arms on behalf of Sheikh Mujib (Mujibur Rahman) and demand autonomy for Bangladesh.”

What India was hoping for “was a transition to democracy in Pakistan”, Dasgupta said. “The Awami League won an absolute majority of seats in the Pakistan National Assembly in the December 1970 elections. New Delhi hoped to see the Awami League-led government installed in power in Islamabad, because we believed that that was the only hope for a breakthrough in Indo-Pakistan relations as a whole.”

However, hopes of a democratic transition were smashed on March 25, when the Pakistani military began a brutal crackdown that resulted in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis and a massive refugee crisis, he said. “Then, we (India) decided to intervene.”

The question of timing

But India knew that immediate military intervention would be counterproductive. “It would result in loss of all international sympathy and support for the Bangladesh cause. It would be viewed simply as another India-Pakistan conflict, a case of Indian intervention in the domestic affairs of Pakistan, and an attempt to promote a secessionist movement.”

Even before General Sam Manekshaw had conveyed the Army’s position that entering the war would have to wait until after the monsoon, “the government was quite clear that…the diplomatic and political ground would have to be prepared before the military intervention”, he said.

Records from the Prime Minister’s Office show that “Mrs (Indira) Gandhi had decided against an immediate early intervention even before that famous sort-of-briefing session with Manekshaw.” Also, the “very careful record” by then Deputy Director of Military Operations Maj Gen Sukhwant Singh states that “political compulsions clinched the issue (of timing)”.

“If the creation of an independent Bangladesh was achieved by Indian military action, how was its domestic and external viability to be assured without its recognition by the international forum, the United Nations? If India intervened without clearly justifying the action in foreign eyes, the charge that it was engineering the break-up of Pakistan would be established and Bangladesh would be refused recognition by the majority of nations,” Dasgupta said.

The diplomatic strategy

So “the first task of the foreign ministry was to promote international sympathy and support for Bangladesh,” Dasgupta said. “Of course, the Bangladeshis were doing this very effectively themselves, but we assisted them in a major way.” The second task was to “explain to the international community that the problem in East Bengal was not simply an internal problem of Pakistan — that by driving out millions of refugees into India, Pakistan was exporting a domestic problem to India. And, this threatened to destabilise the political situation in the neighbouring states.”

Third, “we had to ensure uninterrupted and timely supply of military equipment”, Dasgupta said. “For this, we turned to the Soviet Union. We had to take diplomatic measures to deter possible Chinese intervention and the Soviet Union Treaty achieved this purpose. We also had to ensure the UN Security Council veto did not halt operations before a decisive conclusion could be reached.”

It was not until November 30 that New Delhi received the final assurance of the Soviet support in the UN Security Council, and an understanding that the objective was the emergence of an independent Bangladesh, Dasgupta said.

Architects of victory

The common criticism that India won the war but lost peace with Pakistan is “totally misplaced”, Dasgupta said. “The principal aim of the war had nothing to do with Kashmir; it was to speed up the emergence of an independent state of Bangladesh… We won the peace at the (1972) Simla Agreement, which was meant to seek solutions bilaterally with Pakistan rather than in international fora.”

India’s achievement was all the more remarkable in the absence of supporting institutional structures — it had no equivalent of the US National Security Council, nor even an integrated structure for the three defence services, Dasgupta said.

The credit for formulating the grand strategy and overseeing its implementation goes to a small circle of officials who enjoyed Indira’s trust and confidence — Principal Secretary Haksar, Foreign Secretary Kaul, Ambassador to the USSR D P Dhar, and R&AW chief R N Kao. “Haksar derived his authority from the PM, and his leading role was never questioned…the core group met frequently, often in the presence of Gen Manekshaw, who, in turn, kept the other service chiefs in the picture.” The members of this quintet were on easy and informal terms, and were able to work together in harmony.

External fronts

USSR

Initially unsympathetic to India’s refugee crisis

G Parthasarathy, Dec 15, 2021: The Times of India

India and Bangladesh are now recalling and celebrating the events of 1971 that marked the birth of Bangladesh. It was a period when the two halves of Pakistan, the East and the West, were separated by over 1,000km of Indian territory. It was also a period when the world order was witnessing tumultuous changes, with a right wing US President Richard Nixon seeking a virtual alliance with China’s Communist Party czar Mao Tse-tung. Nixon was determined to seek such an alliance with Beijing primarily to curb and contain communist Soviet Union amid serious territorial and other disputes between Moscow and Beijing.

Despite territorial and other differences, India had no interest in escalating tensions with Beijing. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was then celebrating her huge electoral victory in India. She was looking forward to peace and economic development in an era when India was developing a clear military edge over Pakistan. What India had not envisaged was that it would get drawn into a fratricidal conflict between the eastern and western halves of Pakistan, resulting in the inflow of over 10 million refugees from East Pakistan.

PM Gandhi moved dexterously in her efforts in the days preceding the conflict. The primary effort was to ensure Soviet support at a time when the none too friendly Nixon was determined to build bridges with China. But this was easier said than done. Her meetings in Moscow in October were marked by the presence of the entire Soviet leadership comprising Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, President Podgorny and Prime Minister Kosygin. It, however, appeared clear that while Brezhnev and Podgorny understood the Indian position that it could not be expected to play host to 10 million refugees for any length of time, Kosygin dismissed such thinking. He told Indian correspondents later that evening that any talk of India crossing the border into Bangladesh, in an effort to facilitate the return of refugees, was unacceptable. Kosygin had played a key role in the Tashkent Agreement that ended the 1965 war and was fully versed with India-Pakistan relations. He was also keen to improve relations with the US that would help the rather fragile USSR economy.

The controversies arising from Kosygin’s remarks kept members of the Indian and Soviet delegations working for hours past midnight as there were serious concerns in India about his comments becoming public. This compelled Kosygin to withdraw his earlier comments when he met Indian correspondents at the Moscow airport during Mrs Gandhi’s departure. It was clear that his Politburo comrades, including Brezhnev and Podgorny, did not accept his views. Fully appreciating the seriousness of the situation, the Indian press blocked out any reference to Kosygin’s ill-advised comments after they heard his explanation that he had been misunderstood. D P Dhar (India’s ambassador to the Soviet Union until mid-1971) and Nicolai Pegov, then Soviet ambassador in India, played a key role in dealing with this episode.

The 1971 Bangladesh conflict saw a new pattern of alliances in which China, the US and some “non-aligned” countries backed Pakistan and moved Security Council resolutions against India. However, the UK and France – major US allies – had little sympathy for the Pakistani cause. They were averse to joining the US-China axis during the conflict. Most importantly, the Soviet Union vetoed American-backed resolutions seeking a cease-fire and Indian withdrawal, even as the Pakistan army was preparing to surrender in Bangladesh. There were then lobbies in New Delhi ready to shift armed forces and airpower in Bangladesh to the west, as victory in the east was around the corner. It was, however, made clear that India had no intention of doing so. Going through the records of what transpired in the talks, it was clear that PM Gandhi had played her cards in her talks skilfully in Moscow, and obtained the full support of the Soviet leadership. It was only appropriate and statesmanlike for defence minister Rajnath Singh to have acknowledged this publicly in a meeting he addressed in Bengaluru last month.

Apart from dealing with a continuing stream of visits by ministers and senior officials to Moscow, officials like me also facilitated visits by senior Awami League politicians like Abdus Samad Azad, who became Sheikh Mujib’s foreign minister after the liberation of Bangladesh. Officials of the Soviet Communist Party appeared keen to meet members of the Awami League to understand their political role.

We had a fair idea of what was transpiring in the Pakistan embassy in Moscow and a particular interest in seeing how their two Bangladeshi officials, counsellor Abdus Kibria, who was dealing with economic issues, and the young first secretary Reazul Hussein from the foreign office, would react to the creation of Bangladesh. Both officials contacted us just after the conflict ended, stating their wish to leave the Pakistan embassy. The Soviets cooperated with us on this matter too and granted them stay. Both were involved in the setting up of a new Bangladesh embassy when the first Bangladesh ambassador arrived.

(The author is a former Indian high commissioner to Pakistan and Australia and was a diplomat with the Indian embassy in Moscow during the 1971 war)