Freedom of the press/ media, safety of journalists: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Court judgements

1981: import duties on newsprint

February 19, 2021: The Times of India As part of a series curated by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, on landmark cases that have defined freedom of expression. This piece is compiled by Veera Mahuli, Research Fellow, Vidhi

What the Supreme Court said in 1981, on how newsprint duties impact freedom of the press in India

In 1981, the Indian government began levying import duty on newsprint imported from abroad along with an auxiliary customs duty. This resulted in an increase in the price of newspapers and reduced their circulation. These levies were challenged by several publishers, editors and printers of daily newspapers for stifling their freedom of speech and expression. In response, the government argued that these duties had been levied on newsprint in ‘public interest’ so as to augment revenue.

While deciding this matter, the Supreme Court held that the freedom of press was encompassed within the contours of the ‘freedom of speech and expression’. This freedom, the Court explained, means freedom from interference from any authority which would have the effect of interference with the content and circulation of newspapers.

The Court arrived at this conclusion by recognising how a free press is integral to social and political discourse:

“[T]he press has now assumed the role of the public educator making formal and non-formal education possible in a large scale particularly in the developing world, where television and other kinds of modern communication are not still available for all sections of society. The purpose of the press is to advance the public interest by publishing facts and opinions without which a democratic electorate cannot make responsible judgments …”

The Court further held that there could not be any restriction on the freedom of the press in public interest. The Court ventured into the complex question of ‘Press versus Government’ and noted:

“... Newspapers being purveyors of news and views having a bearing on public administration very often carry material which would not be palatable to Governments and other authorities. The authors of the articles which are published in newspapers have to be critical of the actions of Government in order to expose its weaknesses. ... Governments naturally take recourse to suppress newspapers publishing such articles in different ways.”

On the question of permissible levies on newsprint, the Court’s attention was drawn to a particular statement by the then Finance Minister – that one of the reasons for the Government to impose customs duty on newsprint was that the newspapers contained “piffles”, or “foolish nonsense” which could be done away with. The Court confronted this by saying that even if the writings in the newspaper are piffles, “it cannot be a ground for imposing a duty which will hinder circulation of newspapers.” The government cannot arrogate to itself the “power to prejudge the nature of contents of newspapers”, and imposition of such a tax restriction amounts to conferring on the government the “power to pre-censor a newspaper”.

The Supreme Court ultimately held that the government was indeed empowered to levy taxes affecting the publication of newspapers but within reasonable limits and so as not to impinge on the freedom of expression. In the particular facts before it, the Court observed that the excessive nature of the burden owing to the levy of duties on newsprint was neither adequately proven by the petitioners nor adequately refuted by the respondents. In a finely nuanced judgment, the Court directed the government to re-examine the taxation policy by evaluating whether it constituted an excessive burden on the newspapers.

This judgment is a landmark for establishing a cogent connection between the freedom of speech and expression, the role of the press in a democracy, and people’s right to know. It is of particular relevance in present times, given that in 2020, India was ranked 142nd on the World Press Freedom Index, released by the international organisation Reporters Without Borders. At a time when the means of access to information have substantially increased, the quality of such information is critical. To ensure this, it is imperative that the press remains free from censorship imposed at the state’s behest. At the same time, the judgment places a weighty obligation on the press to report responsibly and in a manner which befits its role as the educator of the masses. A free press is part of our cherished constitutional values, and it is indeed urgent for this beacon to continue shining.

SC’s 6 rules to guard Press freedom/ 2020

Dhananjay Mahapatra, SC lays down 6 rules to guard Press freedom, April 25, 2020: The Times of India

The Supreme Court outlined six cardinal principles to protect journalistic freedom guaranteed under Article 19 and said criminal process should not assume a vexatious character by filing of FIRs for the same cause in many states.

Hearing a case involving a TV anchor, a bench of Justices D Y Chandrachud and M R Shah allowed investigation into one FIR in Mumbai against the anchor while simultaneously staying proceedings in similar FIRs lodged by Congress activists. The bench also stayed proceedings in all FIRs for three weeks to permit the anchor to seek anticipatory bail.

The bench also said no investigation in any FIR except the one lodged in Nagpur, which has been ordered to be transferred to Mumbai, or any future FIR will be proceeded with.After hearing senior advocates Mukul Rohatgi for the anchor and senior advocates Kapil Sibal for Maharashtra, Vivek Tankha for Chhattisgarh and Manish Singhvi for Rajasthan, the Justice Chandrachud-led bench said a balancing of six principles was required to ensure fair administration of criminal justice. The principles are:

• Need to ensure that criminal process does not assume the character of a vexatious exercise by institution of multifarious complaints founded on the same cause in multiple states

• Need for the law to protect journalistic freedom within the ambit of Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution

• Requirement that recourse be taken to remedies available to every citizen in accordance with the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973

• Ensuring that in order to enable the citizen to pursue legal remedies, a protection of personal liberty against coercive steps be granted for a limited duration

• Investigation of an FIR should be allowed to take place in accordance with law without SC deploying its jurisdiction under Article 32 to obstruct due process of law

• Assuaging the apprehension of the petitioner of a threat to his safety and the safety of his business establishment.

The MediaOne case (2010-23)

Sunil Baghel, April 16, 2023: The Times of India

A deeper look at the Supreme Court order which quashed the centre's telecast ban on Malayalam news channel MediaOne, and pulled up the ministry of home affairs for raising national security claims from "thin air" without facts

On April 5, the Supreme Court dealt a major blow to the central government over the issue of press freedom and maintaining secrecy while executing stringent action. This came up when a bench, headed by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, set aside the Kerala high court order, which had upheld the centre's decision to ban Malayalam news channel, MediaOne, on national security grounds.

The court also pulled up the ministry of home affairs for raising security claims out of “thin air”, while setting parameters for the use of sealed covers in court. This will help in curbing the government from getting away with taking harsh action against a person/organisation without having to reveal the reasons for taking that decision.

The top court also stated that critical views of the channel against government policies cannot be termed ‘anti-establishment’ as an independent press is necessary for robust democracy. “National security claims cannot be made out of thin air, there must be material facts backing it,” the bench said.

What the court said on media’s role

“An independent press is vital for the robust functioning of a democratic republic,” the bench said. “Its role in a democratic society is crucial as it shines a light on the functioning of the state. The press has a duty to speak truth to power, and present citizens with hard facts, enabling them to make choices that propel democracy in the right direction.”

The court also made its displeasure known over the note submitted by the Intelligence Bureau, which alleged that the channel’s main source of income was through an investment it received from Jamaat-e-Islami (Hind) cadres and sympathisers. (It also claimed that most of the board of directors were JEI-H sympathisers.)

The note, presented to the court in a sealed cover, also alleged that the channel had an anti-establishment stance, especially on how it covered issues of Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), Armed Forces (Special Power) Act, developmental projects of the government, encounter killings, and CAA/NPR/NRC. It also showed how this was in violation of the Union home ministry’s guidelines on two counts:

The channel’s “involvement” in religious proselytisation activities in India

Its intentional or systemic infringement of safety concerns or security systems endangering the safety of the public

Timeline of the MediaOne case

May 19, 2010: Madhyamam Broadcasting Ltd (MBL) applied for permission to uplink and downlink a news and current affairs television channel named ‘Media One’

February 7, 2011: MHA granted a security clearance for the operation of the channel

September 30, 2011: Ministry of information & broadcasting (MIB) gave MBL permission to uplink ‘Media One’ for a period of ten years under the ‘Policy Guidelines for Uplinking of Television Channels from India

February 12, 2016: The I&B ministry issued a show cause notice to MBL proposing to revoke the permission for uplinking and downlinking granted to MediaOne

February 19, 2016: MBL applied to renew the licence to downlink the channel Media One since the licence which was initially granted for five years had expired

July 11, 2019: MIB renewed the downlinking permission of ‘Media One’ for a further period of five years

May 3, 2021: MBL applied to renew the downlinking and uplinking permissions granted to operate Media One since they were to expire on 30 September 2021 and 29 September 2021

January 5, 2022: The ministry issued another show cause notice to MBL and proposed to ‘revoke’ the permission granted to operate MediaOne

January 19, 2022: MBL replied saying it did not receive any intimation of the denial of security clearance to its MediaOne Channel as stated in the show cause notice

January 31, 2022: The ministry refused to renew MediaOne TV’s transmission licence, barring them from continuing operations. It cited national security concerns, indicating that the Union had issues with the content aired by the channel

February 8, 2022: Kerala HC upheld the order passed by the ministry to revoke the broadcasting licence granted to MediaOne TV

March 2, 2022 A division bench of Kerala HC dismissed MBL's challenge against the single judge's order

March 15, 2022: SC stayed the ban and permitted MediaOne to resume operations, at which time its management announced it would continue broadcasting as it had before the ban was imposed

April 5, 2023: SC quashed the Centre's denial of security clearance to MediaOne

Editors Guild of India’s members: Manipur, 2023

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Sep 16, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi: Shielding journalists’ right to free speech, the Supreme Court Friday said it would be “egregious” to prosecute journalists for false statements in their reports and extended protection for three Editors Guild of India members from arrest in the FIRs lodged against them for a controversial report on media coverage and government handling of ethnic clashes in Manipur.

A CJI-led bench said Section 153A of IPC (promoting enmity) could not be invoked for such false statements. “The report may be right or wrong. But that is what free speech is all about,” it said as a Meitei NGO alleged falsehoods propagated by Kukis in the EGI report.

Safety of Journalists

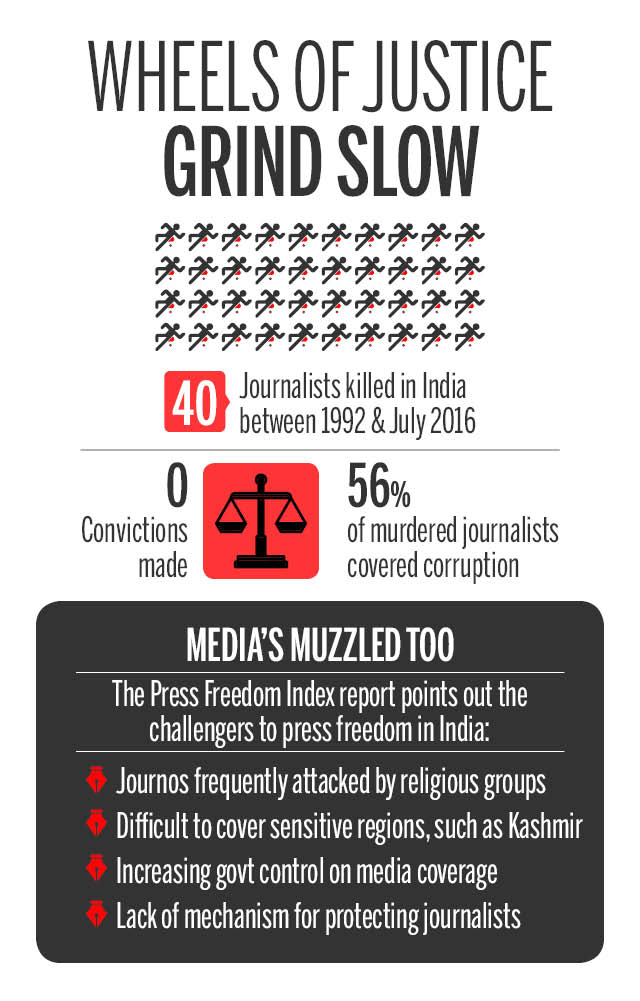

Journalists Killed, 1992-2016

Newsflicks Sparks , Press “India Today” 31/10/2016

See graphic, The number of journalists killed in India and nine other countries, 1992-2016

Newsflicks Spark , Press “India Today” 31/10/2016

See graphic, Journalists killed in India, 1992-2016: convictions made

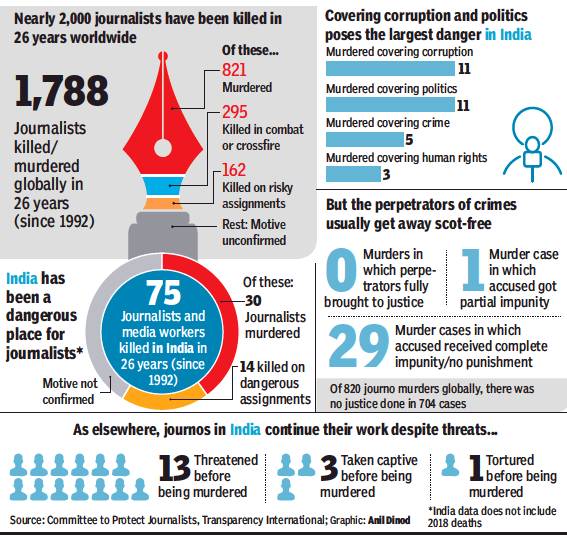

Journalists killed in India, 1992-2018

From April 2, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

Journalists killed in India, 1992-2018: convictions made

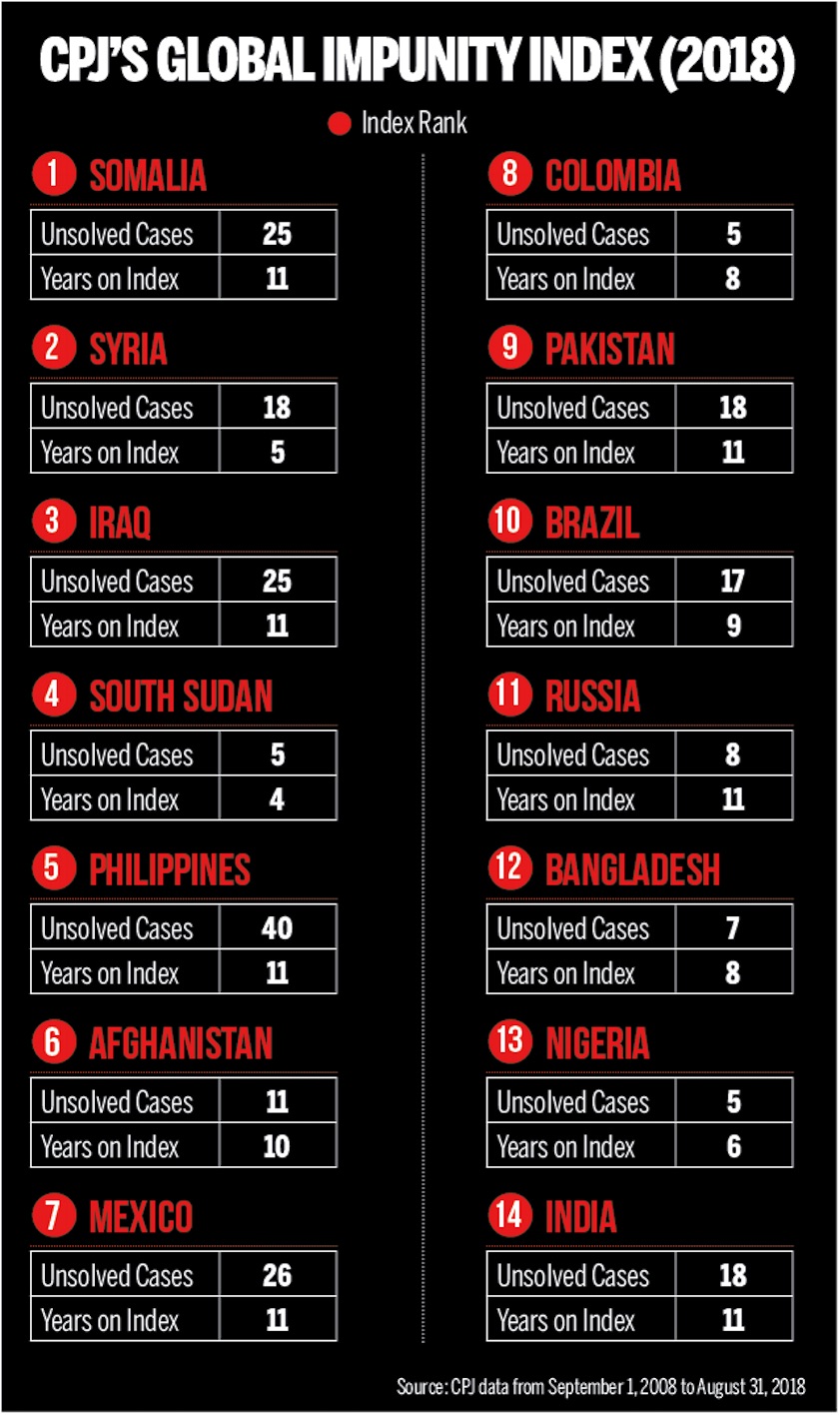

2018: Global Impunity Index

From: October 30, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

Global Impunity Index 2018: Afghanistan was the 6th worst, followed by Pakistan 9th, Bangladesh 12th and India 14th

How free is the Press in India?

2016

Newsflicks spark , Press “India Today” 31/10/2016

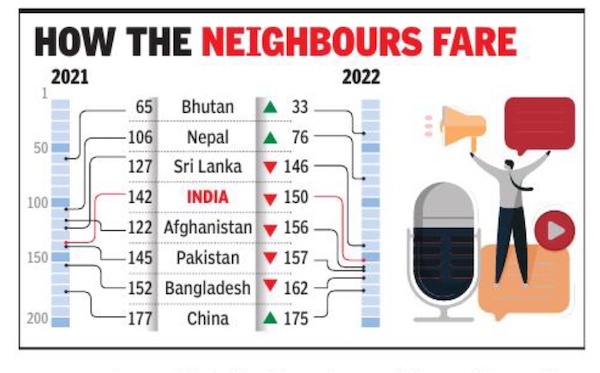

See graphic, The Press Freedom Index, 2016, and the ranks of Bhutan, Nepal, India, Pakistan and China

See graphic:

The Press Freedom Index, 2016, and the ranks of Bhutan, Nepal, India, Pakistan and China

2018: World Press Freedom Index

From: April 27, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

2018- Nepal was ‘problematic;’ India and other South Asian countries were ‘bad;’ and India dropped two places to no. 138

2019: 140/180: India drops 2 slots

140/180: India drops 2 slots on Press Freedom Index, April 19, 2019: The Times of India

India has dropped two places on a global press freedom index to be ranked 140th out of 180 countries in the annual Reporters Without Borders analysis released on Thursday, with the lead up to the ongoing Indian general elections flagged as a particularly dangerous time for journalists.

The ‘World Press Freedom Index 2019’, topped by Norway, finds an increased sense of hostility towards journalists across the world, with violent attacks in India leading to at least six Indian journalists being killed in the line of their work last year.

“Violence against journalists — including police violence, attacks by Maoist fighters and reprisals by criminal groups or corrupt politicians — is one of the most striking characteristics of the current state of press freedom in India...,” the index noted.

These murders highlighted the many dangers that Indian journalists face, especially those working for non-English-language media outlets in rural areas, it said.

Attacks against journalists by supporters of ruling BJP increased in the run-up to general elections 2019, the analysis alleged.

Paris-based Reporters Sans Frontieres (RSF), or Reporters Without Borders documents and combats attacks on journalists around the world. In reference to India, it found an alarming rate of “coordinated hate campaigns waged on social networks against journalists who speak or write about subjects that annoy Hindutva”. PTI

The index finds an increased sense of hostility towards journalists, with violent attacks in India leading to at least six Indian journalists being killed

2021: India remains at no. 142

Anam Ajmal , April 21, 2021: The Times of India

India retained its lowly 142 rank out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders 2021 annual report. The report also categorised India as “one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists trying to do their job properly.”

Published annually since 2002, the report’s Index ranked180 countries according to the level of freedom available to journalists. India has consistently dropped in the ranking starting 2016, when it was placed at 133.

The report also noted that four journalists were killed in India in connection with their work in 2020. It also said the rising instances of journalists being charged with sedition, which is punishable by life imprisonment.

“(In India) journalists who dare to criticise the government are branded as “anti-state,” “antinational” or even “pro-terrorist” by supporters of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). This exposes them to public condemnation in the form of extremely violent social media hate campaigns that include calls for them to be killed, especially if they are women,” the report stated.

It added that journalists are also “physically attacked by BJP activists, often with the complicity of the police” and then subjected to criminal prosecutions.

China was ranked 177, with just Turkmenistan, North Korea and Eritrea placed below it. The report noted that “by using new technologies, Chinese authorities have tightened their grip on news and information even more since the emergence of Covid.” Pakistan was ranked 145, with the report highlighting that the media had become a target of the country’s military.

The US gained one rank and stood at 44, with the report noting that the “first100 days of Joseph R. Biden’s presidency saw healthy improvements to government accountability and transparency.”

2022

Swati Mathur, May 4, 2022: The Times of India

From: Swati Mathur, May 4, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi: India has fallen eight places from 142 to 150 in the 2022 World Press Freedom Index of 180 countries. The index, published by Reporters Without Borders, points to an overall two-fold increase in media polarisation creating divisions within countries, and between countries at the international level.

India’s ranking, as per the report, fell on the back of increased “violence against journalists” and a “politically partisan media”, which has landed press freedom in a state of “crisis” in the world’s largest democracy. The index says, media in India, among nations reputed to be more democratic, faces pressure from “increasingly authoritarian and/or nationalist governments”, a transformation seen since PM Narendra Modi took over the reins of the country in 2014. “Very early on, Modi took a critical stance vis-à-vis journalists, seeing them as ‘intermediaries’ polluting the direct relationship between himself and his supporters. Indian journalists who are too critical of the government are subjected to allout harassment and attack campaigns by Modi devotees known as ‘bhakts’,” the report says.

It also faults India for its policy framework, which is protective in theory but resorts to using charges of defamation, sedition, contempt of court and endangering national security against journalists critical of the government, branding them as “anti-national. ”

With an average of three or four journalists killed in connection with their work every year (one killed since January 2022 and 13 currently in prison), India, according to the report, is also one of the world’s most dangerous countries for mediapersons. “Journalists are exposed to all kinds of physical violence including police violence, ambushes by political activists, and deadly reprisals by criminal groups or corrupt local officials. . . ” it said.

The World Press Freedom Index also says the situation in Kashmir remains “worrisome” and reporters are often harassed by police and paramilitaries. A joint statement by the Press Club of India, Press Association and the Indian Women’s Press Corps, said attacks on media grew in “myriad ways”.

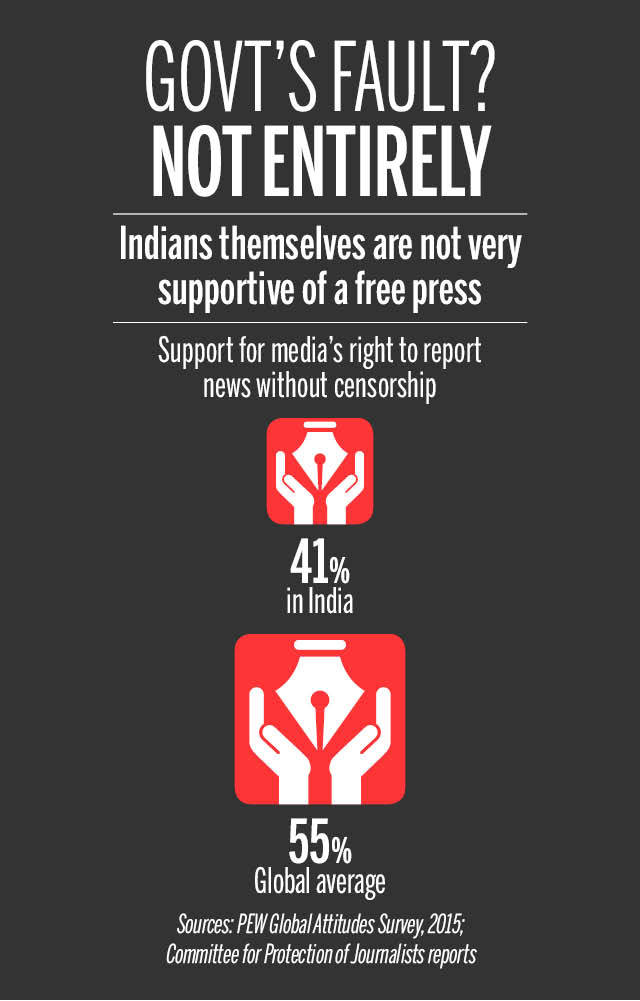

How supportive is the public?

Newsflicks Spark , Press “India Today” 31/10/2016

See graphic, How supportive is the public?

See also

Censorship of the arts and media: India

Information Technology Act: India